2017-18 Annual Report to Parliament on the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act and the Privacy Act

Trust but verify: Rebuilding trust in the digital economy through independent, effective oversight

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

30 Victoria Street

Gatineau, QC K1A 1h2

© Her Majesty the Queen of Canada for the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, 2018

Cat. No.: IP51-1E-PDF

ISSN: 1913-3367

Follow us on Twitter: @PrivacyPrivee

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/PrivCanada/

Letter to the Speaker of the Senate

The Honourable George J. Furey, Senator

The Speaker

Senate of Canada

Ottawa, Ontario

K1A 0A4

September 2018

Dear Mr. Speaker:

I have the honour to submit to Parliament the Annual Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, for the period from April 1, 2017 to March 31, 2018. This tabling is done pursuant to sections 38 for the Privacy Act and 25 for the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act.

Sincerely,

Original signed by

Daniel Therrien

Commissioner

Letter to the Speaker of the House of Commons

The Honourable Geoff Regan, M.P.The Speaker

House of Commons

Ottawa, Ontario

K1A 0A4

September 2018

Dear Mr. Speaker:

I have the honour to submit to Parliament the Annual Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, for the period from April 1, 2017 to March 31, 2018. This tabling is done pursuant to sections 38 for the Privacy Act and 25 for the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act.

Sincerely,

Original signed by

Daniel Therrien

Commissioner

Commissioner’s message

The Facebook/Cambridge Analytica crisis

Sometimes it takes a crisis to effect change and this past year has seen no shortage of privacy crises.

There were the unfortunately familiar data breaches, affecting millions of customers of companies like Equifax, Uber and Nissan Canada Finance, to name a few. And there was of course the Facebook/Cambridge Analytica matter, which we are now investigating, widely seen as a serious wake-up call that highlighted a growing crisis for privacy rights.

With the Facebook matter, individuals must now confront the idea that personal information may be analyzed for far more insidious purposes than marketing. In this instance, the allegations are that our information was used to influence political opinions. What next? How else are we being manipulated?

These issues also underscore deficiencies in Canada’s privacy laws that I and my predecessors have tried to draw attention to for years. This past year alone, we’ve had numerous opportunities to highlight those deficiencies and propose potential solutions.

We have testified and made submissions to parliamentarians on the need to modernize the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA), and proposed changes to national security legislation, Bill C-59, in which we reiterated a number of the recommendations we made on Privacy Act reform in 2016, among other things.

We also drew attention to the lack of standards and oversight over the personal information handling practices of political parties. The government introduced legislation intended to respond to this important gap.

Bill C-76, however, adds nothing of substance in terms of privacy protection. Rather than impose internationally recognized standards, the bill leaves it to parties to define the rules they want to apply. It does not impose independent oversight. On this and many other fronts, Canada’s privacy legislation is sadly falling behind what is the norm in other countries.

Canadians want to enjoy the many benefits of the digital economy, but they rightly expect they can do so without fear that their rights will be violated and their personal information will be used against them. They want to trust that rules, legislation and government will protect them from harm.

The time of self-regulation is over. In Canada we, of course, have privacy legislation but it is quite permissive and gives companies wide latitude to use personal information for their own benefit. Under PIPEDA, organizations have a legal obligation to be accountable, but Canadians cannot rely exclusively on companies to manage their information responsibly. Transparency and accountability are necessary but they are not sufficient.

To be clear, it is not enough to ask companies to live up to their responsibilities. Canadians need stronger privacy laws that will protect them when organizations fail to do so. Respect for those laws must be enforced by a regulator, independent from industry and the government, with sufficient powers to ensure compliance.

Trust but verify. In order to increase trust in the digital economy, we must ensure that Canadians are able to count on an independent third party who can verify compliance with privacy laws.

Given the opaqueness of business models and the complexity of information flows in the age of data analytics, artificial intelligence (AI) and the Internet of Things, that regulator, my Office federally, should be authorized to inspect the practices of organizations even if a violation of law is not immediately suspected. Individuals are unlikely to file a complaint when they are unaware of a practice that may harm them.

In other words, trust but verify. In order to increase trust in the digital economy, we must ensure that Canadians are able to count on an independent third party who can verify compliance with privacy laws.

We have also asked Parliament to study the issue of de-indexing and source takedown with a view to confirming the right balance between the right to reputation and privacy, freedom of expression and public interest.

On the public sector side, we have proposed amendments to Bill C-59 that strike a better balance between national security and respect for basic individual rights, including the right to privacy.

Progress from government slow to non-existent

Several parliamentarians have supported our call for legislative reform. Notably, in February, 2018, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics (ETHI), which is tasked with reviewing Canada’s privacy laws, concurred with many of our recommendations to amend PIPEDA, and even called for additional measures inspired by the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which came into force in May.

In a later report in June, after hearing from witnesses on the Facebook/Cambridge Analytica matter, ETHI came to the view that some amendments (notably those conferring new enforcement powers to my Office, including the power to inspect or audit) were urgently required. ETHI also agreed that political parties need to be governed by privacy laws.

Unfortunately, progress from government has been slow to non-existent. The only clear support was for a majority of the amendments we suggested to Bill C-59, the anti-terrorism bill. As regards the Privacy Act, adopted 35 years ago to regulate privacy in the public sector, the Minister of Justice announced in 2016 that she had instructed her officials to begin concentrated work towards modernizing the law – an exercise she agreed was long overdue. Yet no concrete proposal has yet been made public.

In late June 2018, the government responded to ETHI’s recommendations to amend PIPEDA. The Minister of Innovation, Science and Economic Development agreed that changes are required to our privacy regime, but he argued that further study of the viability of all options, for instance on enforcement models, was required with a view to presenting Canadians with proposals. The minister launched a national digital and data consultation, which could eventually result in amendments to the law in several years.

Canadians cannot afford to wait several years until known deficiencies in privacy laws are fixed. Technology is evolving extremely rapidly and many new technologies disrupt not only business models but also social and legal norms. Legal protections must improve apace if consumer trust is to reach the level everyone desires. As ETHI commented in its June report, “the urgency of the matter cannot be overstated.”

We are of course not asserting that we have reached a stage where all privacy risks are known and all solutions have been identified. There is therefore merit in the consultations announced by the government. However, several deficiencies in the law have been identified for some time, including the issue of necessary powers for the Office of the Privacy Commissioner (OPC).

We know Canadians want this and we know organizations generally would prefer not being subject to inspections, orders and fines. There is no need to consult on this issue. Now is the time to act.

While we were disappointed with the government’s response, we did not wait for government to act and have undertaken a number of initiatives in areas where we do have some control. However, these were in the form of guidance, not law, and the protection they offer to Canadians is therefore limited.

Guidelines on meaningful consent and inappropriate practices

Last year in our Annual Report, we concluded that consent should continue to play a prominent role in the 21st century, as it is central to personal autonomy. Consent has an important place in privacy protection, where it can be meaningfully given with sufficient information.

Where consent may not be practicable, for instance in certain situations involving AI where data may be used for multiple purposes not always known when it is collected, other forms of privacy protection may be required. We also concluded that in all situations, additional support mechanisms are needed. This includes independent regulators that can guide industry, hold it accountable, inform citizens and meaningfully sanction inappropriate conduct.

To more effectively guide industry and help individuals in exercising their privacy rights, in May 2018, we published two important guidance documents on obtaining meaningful consent and inappropriate data practices. They marked the culmination of an extensive consultation process, which included an opportunity for stakeholders to provide feedback on draft versions released in the fall.

The consent guidance sets out advice for organizations to ensure they obtain meaningful consent. It describes seven guiding principles, including the need to emphasize four key elements in privacy notices:

- what information is being collected;

- with whom is it being shared;

- for what purposes is it being collected, used or disclosed, and

- meaningful residual risk of significant harm.

The guidance on inappropriate practices outlines for companies which practices are inappropriate and informs individuals about what organizations are generally prohibited from doing, even with consent. This includes:

- profiling that leads to discriminatory treatment contrary to human rights law;

- collecting, using or disclosing personal information for purposes that are known or likely to cause significant harm to the individual, or

- posting personal information with the intent of charging a fee for its removal.

Our Obtaining meaningful consent guidance was a joint effort with our counterparts in Alberta and British Columbia and will apply as of January 1, 2019, as we want to give organizations time to implement changes to their systems and practices. Our Inappropriate data practices guidelines became applicable as of July 2018.

Generally speaking, the documents set out a combination of legal requirements and best practices that detail our expectations regarding what compliance entails. Once these guidelines are in application, it will be through this lens that our Office conducts its work.

I know some stakeholders were concerned about binding language in the guidance. While it is clear that we cannot use guidance to establish new legal standards, we think our role as a regulator includes giving guidance that clarifies broadly framed PIPEDA principles and sets expectations as to how the law should generally be interpreted and applied.

Given that PIPEDA is so broad in its formulation, individuals and organizations need an adequate level of certainty as to what compliance entails. It is troubling that some organizations have signaled an interest in challenging the legality of this approach. This is another reason why legislative reform is required, since having the authority to make orders would go a long way to addressing such challenges. We note that in his response to ETHI, the Minister of ISED acknowledged that “more specific guidelines or regulations may need to be articulated” to clarify PIPEDA principles “for new or emerging business models or products.”

Read more about how stakeholder feedback was incorporated into the final versions of the guidance documents.

Reputation

In January, my Office released the results of a public consultation related to important questions around online reputation and privacy.

We approached this work with one key goal in mind: helping to create an environment where individuals may use the Internet to explore their interests and develop as persons without fear that their digital trace will lead to unfair treatment.

The nature of information has changed dramatically in the digital age, creating new risks to the reputation of individuals. Social media and search engines make it much easier to have access to information. Information about us is readily available to potentially millions of people – and that information may be inaccurate, years out of date, or presented out of context.

And yet, key decisions are made about us based on searches done on social media platforms or using search engines– for example, decisions related to employment, housing or credit. So, there are real consequences.

This raises questions: as a society, do we believe reputation deserves protection against the new risks posed by the online realm? And, if yes, what form should it take?

We examined various mechanisms aimed at providing individuals with some measure of control over their online information. We looked for options that would respect the balance between privacy and other critical rights, such as freedom of expression and freedom of the press.

We ultimately came to the conclusion that the most appropriate way forward was to interpret PIPEDA in a way that protects people’s online reputation. We believe that under the existing law, Canadians have a right to ask search engines to de-index web pages, and websites to remove or amend content, that contains inaccurate, incomplete or outdated information.

Our draft position on online reputation also highlighted the need to educate young Canadians in order to help develop responsible, informed online citizens.

In the months following the publication of that draft position paper, we further consulted with stakeholders.

In the meantime, our Office received complaints from individuals about Google search results. In response, Google took the position that PIPEDA did not apply to its search engine and that, in the alternative, de-indexing would be unconstitutional if the Act did apply. We therefore plan to file a reference with the Federal Court to first seek clarity on the issue of whether Google’s search engine is subject to PIPEDA before proceeding further with the complaints.

We also called on the government to amend the law to effectively protect reputation in an increasingly online world. We are glad that the government, in its response to ETHI’s February report, agreed it will be necessary to provide further certainty on how the Act applies in the various contexts where personal reputation may be harmed.

A proactive vision for privacy protection

It has become increasingly clear to me that to have a greater impact on the privacy rights of more Canadians, we need to change our approach as a regulator.

To that end, we have made significant changes to our organizational structure that we believe will help us achieve better results for privacy.

It has become increasingly clear to me that to have a greater impact on the privacy rights of more Canadians, we need to change our approach as a regulator.

We have streamlined our operations by clarifying program functions and reporting relationships, and become more forward-looking by shifting the balance of our activities towards greater pro-active efforts. Our objective is to have a broader and more positive impact on the privacy rights of a greater number of Canadians, which is not always possible when focusing most of our attention on the investigation of individual complaints.

With that in mind, our work now falls into one of two program areas: promotion or compliance. Activities aimed at bringing departments and organizations towards compliance with the law fall under the Promotion Program, while those related to addressing existing compliance issues fall under the Compliance Program.

While we continue to seek stronger enforcement powers, we believe that a successful regulator does not rely first on enforcement, but rather only when needed. Thus our first strategy is under the Promotion Program to inform Canadians of their rights and how to exercise them, and to guide and engage with organizations on how to comply with their privacy obligations.

Guidance and information will be issued on most key privacy issues, starting with how to achieve meaningful consent in today’s complex digital environment and inappropriate data practices as mentioned earlier.

We also wish to work with industry proactively and collaboratively in an advisory capacity, to the extent our limited resources allow. We want to better understand the privacy impacts of new technologies and provide practical advice on how to use them in a privacy compliant way.

For example, we announced in May 2018 our first advisory project involving Sidewalk Toronto, a smart-city endeavor between Waterfront Toronto and Sidewalk Labs, owned by Google’s parent company Alphabet. The initiative involves building a technology-driven neighbourhood on the city’s eastern waterfront that includes sensors aimed at helping city planners find efficiencies.

Understandably, it is raising many questions about data collection, privacy, where the information will be stored and how it might be used.

Along with colleagues from the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario, members of our Business Advisory Directorate met with those behind the project to learn more about it and how they were addressing some of these privacy concerns.

We also reminded officials of key privacy principles, including identifying the purposes for collection, obtaining consent, ensuring individuals could access their own personal information and being accountable for protecting the data and being clear about who owns it.

Overall, we are encouraged by Sidewalk Toronto’s efforts to proactively address privacy and data security in the design and implementation of the initiative. Given the project is still in its early stages, we are continuing to monitor developments and proactively engage with Sidewalk Toronto officials as it progresses. We also hope the advice we provide will be helpful as other smart city initiatives pop up across the country.

Addressing privacy issues upfront and resolving matters cooperatively, outside formal enforcement, is our preferred approach. It avoids time-consuming and costly investigations, helps mitigate against future privacy risks, offers organizations a measure of consistency and predictability in their dealings with our Office and allows everyone to benefit from innovation.

It is for these reasons that we will primarily consider our promotion tools before engaging our second strategy – proactive enforcement.

Under the Compliance Program, our proactive enforcement actions will target systemic, chronic or sector-specific privacy issues that aren’t being addressed through our complaint system and that we believe may inflict significant damage to the privacy rights of Canadians.

For example, we launched our first proactive, Commissioner-initiated investigation under our Compliance Program in May 2018 into the practices of six different data and list brokers.

As part of the investigation, we’re looking at accountability, openness and transparency in the management of personal information and considering the means of consent obtained for the personal information collected, used or disclosed. We believe this industry can benefit from an investigation of this nature, and that Canadian consumers will welcome it.

By delineating our activities more clearly under two programs, Compliance and Promotion, by being more proactive and by ensuring we are citizen-focused, I hope Canadians may begin to feel more empowered and in control of their personal information – and generally safer in the knowledge that their rights will be respected.

Our Government Advisory Directorate is also in the business of providing advice, in this case, to federal institutions, which we’ve committed to doing more frequently. We wish to engage with government stakeholders earlier in the development of programs and activities so that Canadians may enjoy the benefits of innovation without undue risk to their privacy. To that end, we will enhance our guidance related to Privacy Impact Assessments (PIAs) and make it easier for institutions to prepare them.

Of course, the extent to which we can execute our proactive agenda hinges on resources. We have gone to great lengths to find efficiencies and make optimal use of existing resources and tools. Nevertheless, we find ourselves unable to keep pace with the challenges of an increasingly complex digital environment, in no small part because Canada’s privacy laws are not adapted to the realities of the 21st century.

We’ve requested a modest increase in permanent funding to provide interim relief pending much needed legislative reform. If received, these funds would help:

- establish a limited proactive agenda that includes arming organizations with more policy guidance on emerging issues and educating Canadians so they may take control of their privacy;

- deal with mandatory breach reporting which comes into force in November without any associated funding and, as was the case in other jurisdictions, is expected to significantly increase our workload; and

- assist our overwhelmed investigators in more expediently addressing complaints filed by concerned Canadians and proactively investigating systemic, chronic or sector specific privacy issues.

Following the Facebook/Cambridge Analytica matter, we were asked by ETHI what resources and tools my Office might need to assist in ensuring that “tech giants” and other companies truly respect their privacy obligations.

While our modest ask for increased funding would have an interesting but limited impact, a significantly larger budget might be required to actually have a true impact in terms of protecting Canadians’ privacy rights, as envisaged by ETHI. This was the conclusion reached by the U.K. government recently, which decided to double the resources available to my counterpart, the Information Commissioner’s Office. This would equip the OPC with a full suite of properly resourced promotion and compliance tools.

Complete funding would provide for a full set of guidance documents and ensure that they remain current, which is essential when technological leaps result in the creation of new privacy risks every day.

It would allow us to provide advice to more organizations that wish to use new technologies in a privacy compliant way. We have already experienced a great deal of interest in our Office providing more advisory services to business; right now, however, our limited advisory program would not come close to meeting such expressed demand.

In focusing on improving citizen control of their privacy, we could use innovative means such as contextual advertising to bring individuals to our site when they are about to make a decision on whether to disclose their personal information.

Recent events underscore the significant risks facing privacy protection in the digital age. Modern laws consistent with evolving international norms are urgently required if we are to provide Canadians with the protection they expect and deserve.

We would also develop effective strategies with regulators in other fields to ensure companies comply with all applicable laws, which sometimes overlap. And finally, full funding would allow the OPC to be both proactive in investigating opaque privacy practices involving risk, and responsive in a timely way to all complaints, thus achieving a greater scope of compliance amongst public and private institutions.

Final thoughts

To sum up, recent events underscore the significant risks facing privacy protection in the digital age. Modern laws consistent with evolving international norms are urgently required if we are to provide Canadians with the protection they expect and deserve.

We have undertaken several initiatives that are within our powers to enhance this protection, but to be truly effective as a regulator, we need new powers and resources.

ETHI’s Vice-Chair, Nathaniel Erskine-Smith, introduced a private member’s bill in June that would empower my Office to conduct audits, make orders and refer cases involving willful or reckless violations of the law for prosecution, which could result in fines.

I think the time is well past due for the government to introduce legislation along the same lines, albeit amended in such a way as to levy administrative monetary penalties rather than rely on the criminal law. I note that these proposed new powers received all-party support within the ETHI committee.

In addition, we ask the government to increase our resources so that, pending the conclusion of its consultation on a data strategy and broader legislation, my Office has the necessary tools to adequately protect the privacy of Canadians.

Privacy by the numbers

| PIPEDA complaints accepted* | 297 |

|---|---|

| PIPEDA complaints closed through early resolution* | 205 |

| PIPEDA complaints closed through standard investigation* | 106 |

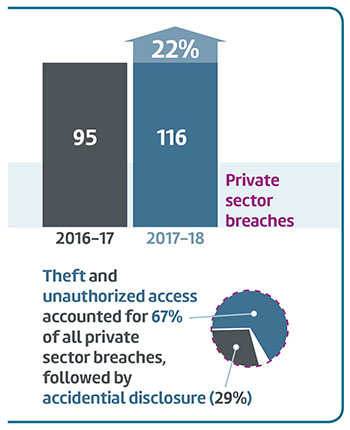

| PIPEDA data breach reports | 116 |

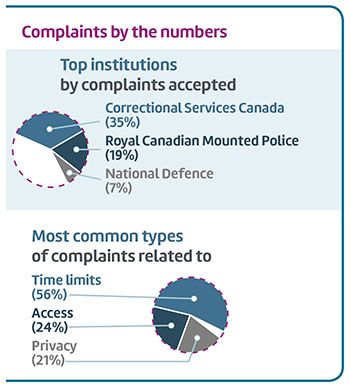

| Privacy Act complaints accepted* | 1,254 |

| Privacy Act complaints closed through early resolution* | 441 |

| Privacy Act complaints closed through standard investigation* | 767 |

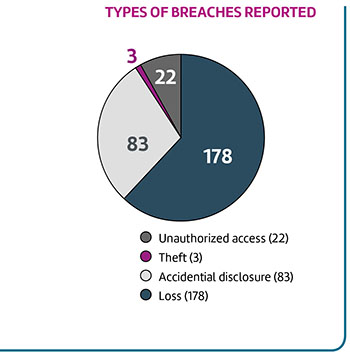

| Privacy Act data breach reports | 286 |

| Privacy Impact Assessments (PIAs) received | 71 |

| Advice provided to public sector organizations following PIA review or consultation | 50 |

| Public interest disclosures by federal organizations | 571 |

| Bills and legislation reviewed for privacy implication (14 bills + 17 studies) | 31 |

| Parliamentary committee appearances on private and public sector matters | 14 |

| Formal briefs submitted to Parliament on private and public sector matters | 20 |

| Other interactions with parliamentarians or staff (for example, correspondence with MPs’ or Senators’ offices) | 11 |

| Information requests | 10,092 |

| Speeches and presentations | 79 |

| Visits to website | 2,095,447 |

| Blog visits | 200,840 |

| Tweets sent | 989 |

| Twitter followers as March 31, 2018 | 13,976 |

| Publications distributed | 55,010 |

| News releases and announcements | 64 |

| * includes one representative complaint for each series of related complaints, see Appendix 2 – Statistical tables for more details | |

The Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act – A year in review

Consent and control

The centrepiece of last year’s Annual Report to Parliament was our Report on Consent. In it, we carefully considered the obligation under PIPEDA that organizations obtain meaningful consent for the collection, use and disclosure of personal information.

In the era of data analytics, AI, robotics, genetic profiling and the Internet of Things, we recognized that the cornerstone of Canada’s federal private sector privacy law was under considerable strain. Nevertheless, we concluded consent remains central to personal autonomy and should continue to play a prominent role in privacy protection, where it can be meaningfully given with sufficient information.

But consent, we said, must be supported by other mechanisms if we are to effectively protect privacy, including independent regulators that inform citizens, guide industry, hold it accountable, and sanction inappropriate conduct.

To that end, a number of our activities this past year were aimed squarely at bolstering consent and control under PIPEDA.

Consent guidance

Shortly after the 2016-17 Annual Report was tabled, we published draft guidance on consent and inappropriate practices which topped a list of 30 topics in last year’s Report on Consent and on which we said we would begin issuing new or updated information and guidance, to the extent our limited resources allow.

We encouraged stakeholders to provide feedback and received 13 submissions, largely from associations representing businesses.

After reviewing the submissions, we revised the guidance and published final versions in May 2018. Our guidance on inappropriate data practices became applicable to businesses on July 1.

Our guidance on obtaining meaningful consent sets out practical and actionable advice for organizations. The guidance on no-go zones sets boundaries that protect individuals from the inappropriate data practices of companies.

Among other important advice in the meaningful consent guidance, including seven guiding principles, we outline four elements that must be emphasized in privacy notices and explained in a user-friendly way:

- what personal information is being collected;

- with which parties personal information is being shared;

- for what purposes personal information is collected, used or disclosed; and

- what risks of harm or other consequences might come from any collection, use or disclosure of the information provided.

For further details on the OPC’s response to stakeholder feedback received on the draft guidance, including why certain changes were, or were not, made to the final versions, see:

Some stakeholders have expressed concerns about our decision to include risk of harm among the elements. This decision flows from the definition of valid consent. It requires that an individual understand not only the nature and purpose, but also the potential consequences of the collection, use or disclosure to which they are consenting.

What we are referring to are those residual risks that might remain despite an organization’s best efforts to apply mitigation measures designed to minimize risk and impact of potential harms. Only meaningful residual risks of significant harm must be included in notifications. By meaningful risk, we mean a risk that falls below the balance of probabilities but is more than a minimal or mere possibility.

Significant harm would be defined as in s.10.1(7) of PIPEDA and include:

- bodily harm,

- humiliation,

- damage to reputation or relationships,

- loss of employment, business or professional opportunities,

- financial loss, identity theft, negative effects on the credit record, and

- damage to or loss of property.

We also heard concerns about binding language in the original draft guidance. While it is clear we cannot use guidance to establish new legal standards, we do believe that our role as a regulator includes giving guidance that clarifies broadly framed PIPEDA principles and sets expectations as to how the law should generally be interpreted. Given that PIPEDA is so broad in its formulation, this type of guidance helps to provide individuals and organizations alike with a degree of certainty in how the legislation applies.

As such, in the final guidance, we distinguish between requirements and best practices or recommendations. It’s an important and useful change that was recommended by stakeholders. In short, we have added a checklist that distinguishes between “must do’s” (what we feel is a legal requirement) and “should do’s” (what we feel is a best practice).

With respect to our new guidance on inappropriate practices, while context is of course important in the application of subsection 5(3) of PIPEDA, we firmly believe there is value in, and even a need for, specific examples of practices that will generally be found inappropriate. This should set useful boundaries for individuals and organizations.

We will begin to apply our guidance on obtaining meaningful consent, which was issued jointly with our Alberta and British Columbia counterparts in January 2019. This will give organizations time to implement any necessary changes to their systems and practices. The OPC guidance on inappropriate practices became applicable as of July 1, 2018.

Reputation

The OPC identified reputation and privacy as one of four strategic privacy priorities in 2015. With the proliferation of social media and new communications technologies, we were concerned about the ease with which people can post information about themselves and others, and the difficulty of removing or amending information once it’s online.

For example, an adult may feel their reputation is harmed by controversial views they held as a teenager and posted online. Other examples could include defamatory content in a blog; photos of a minor that later cause reputational harm; intimate photos; or online information about someone’s religion, mental health or other highly sensitive information.

Our stated goal in identifying this as a priority was to work towards creating an environment where individuals may use the Internet to explore their interests and develop as persons without fear that their digital trace will lead to unfair treatment.

We launched a consultation and call for essays on the issue of online reputation. Based on the submissions received, along with our own analysis, we published a Draft Position on Online Reputation in January that champions solutions that offer a balance among freedom of expression, the privacy interests of individuals and the public interest.

The draft report concludes that Canadians have an existing right under PIPEDA to ask search engines to de-index web pages, and to ask websites to remove or amend content that contains inaccurate, incomplete or outdated information. The proposal draws parallels with the “right to be forgotten” in the European Union.

We also called for:

- greater protections for children and youth upon reaching the age of majority;

- privacy protection to be incorporated into curriculum for digital education across the country to help develop responsible, informed online citizens; and

- Parliament to study the overall issue.

While we recognize de-indexing is not necessarily a perfect solution to protecting reputation, it is nonetheless an important tool that we feel is available under the current law. Still, given competing rights on this issue, we believe it merits an examination by elected officials.

In fact, in its report on PIPEDA reform, ETHI carefully considered the issue, concluding the government ought to amend PIPEDA to include a framework for a right to de-indexing and web content removal based on the European Union model. At a minimum, the committee agreed stronger de-indexing and take-down protections for youth are needed.

In the meantime, our Office has continued to receive complaints relating to Google search results. In responding to one of these complaints, Google asserted that PIPEDA does not apply to its search engine service, contrary to the OPC’s draft position, and that if PIPEDA did require de-indexing of lawful, public content, that would be unconstitutional.

In order to seek clarity on the threshold issue of whether PIPEDA applies to Google’s search engine, we plan to initiate a reference with the Federal Court. The reference will seek a determination as to whether Google’s search engine service collects, uses or discloses personal information in the course of commercial activities and is therefore subject to PIPEDA, and whether Google is exempt from it because its purposes are exclusively journalistic or literary. Our position will remain in draft form and the complaints received will be kept in abeyance pending a resolution by the Court as to the applicability of PIPEDA.

Also in the context of online reputation, the 2017 Supreme Court of Canada decision in Google Inc. v. Equustek Solutions Inc. is worth noting. In this case, the court ruled that it was possible for a Canadian court to grant a worldwide interlocutory injunction against a search engine in order to have it delist websites. While the case had to do with trade litigation, it has implications for privacy and may have ramification for the “right to be forgotten” debate. For more information about this case, see the Privacy cases in the courts section of this report.

PIPEDA review

ETHI completed its study of PIPEDA in February 2018 with the release of a report entitled Towards Privacy by Design: Review of the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act. This included consideration of our Report on Consent, originally published in our 2016-17 Annual Report to Parliament.

The OPC had a number of opportunities to make representations on PIPEDA reform leading up to the report’s release.

We called for the OPC to have the authority to issue orders and the ability to impose administrative monetary penalties in order to deal effectively with those who would not otherwise comply with the law. In our submissions, we stressed that penalties would be imposed to promote compliance, not to punish, and would serve as an important incentive for organizations – noting that these powers would bring us in line with many of our international counterparts.

We also asked for new powers to conduct compliance reviews, even if a violation of PIPEDA is not immediately suspected. This would allow us to more proactively address privacy issues that are unlikely to become subject to complaint as they involve complex business models or opaque data flows of which few Canadians may be aware.

On that note, we argued for more flexibility in choosing which individual complaints to investigate in order to better utilize our limited resources. In addition, should we decline to pursue an investigation, we asked that individuals be granted some form of judicial redress, such as a private right of action.

We were pleased to see the committee conclude that there is a demonstrated need to grant our Office additional enforcement powers and that they took our concerns related to consent and reputation seriously. In some cases, the committee went beyond our recommendations for reforms, effectively calling for changes that would more closely align PIPEDA with the European Union’s GDPR, which came into force in May.

As an example, the committee called for “privacy by design” to be legislated as a central principle for organizations to follow and for the right to data portability. The concept of privacy by design, coined by Ontario’s former privacy commissioner, calls for privacy to be built in at the design phase of any new product or service.

In our representations, we also stressed the importance of maintaining Canada’s “adequacy status” with the European Union. Since 2001, data has been allowed to flow freely from the European Union to Canada. With the GDPR – the new European data protection instrument now in force – decisions about the adequacy of a country’s privacy laws, in terms of whether they afford European citizens protections equal to those of Europe, will be reviewed every four years.

The committee was receptive to these concerns and called on the government to take appropriate action to ensure that the seamless transfer of data between Canada and the European Union can continue.

Last spring’s allegations concerning Facebook and consulting firm Cambridge Analytica thrust privacy issues into the international spotlight. The case, which allegedly involved the collection of personal data from millions of unsuspecting Facebook users for the purposes of swaying political opinion, is now under investigation by the OPC and other regulators.

Not only has it proven to be a wake-up call to many that the time for self-regulation is over, it has also drawn attention to the lack of oversight over the personal information handling practices of political parties. This important gap, in part, prompted the Canadian government to introduce Bill C-76. However, the proposed legislation falls way short of international standards and adds nothing of substance in terms of privacy protection. Far more needs to be done to govern the use of personal information by political parties if the privacy of Canadians is to be adequately protected.

In the wake of this incident, ETHI undertook a review of the privacy implications of platform monopolies and possible remedies to assure the privacy of citizens’ data and the integrity of democratic and electoral processes across the globe. The OPC participated in this review, and in June, ETHI published an interim report entitled Digital Privacy Vulnerabilities and Potential Threats to Canada’s Democratic Electoral Process. The committee called on the government to take measures to ensure privacy legislation applies to political activities and reiterated the need for greater enforcement powers for the OPC. It commented that “the urgency of the matter cannot be overstated.”

At the same time, the government came back with its response to ETHI’s February report on PIPEDA reform. We are encouraged to hear the government agrees Canada’s privacy laws need to be changed, but we are disappointed changes will likely have to wait several years, after the digital and data consultations take place and a federal election is held in the fall of 2019.

We ask the government to act immediately on ETHI’s recommendations aimed at bolstering the enforcement tools in our toolkit – an idea broadly supported by parliamentarians, Canadians and privacy stakeholders.

In addition to our contribution to the ETHI committee study of PIPEDA, our Office participated in other parliamentary reviews that, at their heart, speak to issues of consent and individual control over personal information.

In particular, this involved our advice to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Technology regarding Canada’s Anti-spam Legislation, as well as our advice to the Senate Standing Committee on Transport and Communications regarding connected and automated vehicles in our section on parliamentary appearances.

Summary of key investigations related to consent and control

Microsoft: Giving Windows 10 users a say in what information they provide

In 2016, our Office launched an investigation into a complaint about the default privacy settings offered by Microsoft’s Windows 10 operating system. We wanted to find out if, during the Windows 10 installation process, users had the opportunity to give fully informed consent to the collection and use of their personal information by Microsoft.

Microsoft was cooperative with our Office in making changes to address our recommendations flowing from our investigation. That being said, Microsoft is one of the world’s largest and influential companies, and its Windows operating system is used by over a billion individuals worldwide. We were therefore surprised that Microsoft had not proactively identified and addressed prior to the launch of Windows 10, the many privacy concerns ultimately raised by our Office’s investigation and other data protection agencies around the globe.

During the course of our investigation, Microsoft issued two updates to Windows 10. The most recent, known as the “Creator’s” update, included five new or updated privacy settings: location, diagnostics, tailored experiences, relevant ads and speech recognition. All five of them were set to “on” or “full” by default during the installation of the update. For each of these settings, we had raised concerns about whether Microsoft was giving users the information they needed to make a meaningful decision on consent.

For the “location” setting, for example, we recommended that Microsoft make it clear that third party applications could still determine a user’s location even when this feature was turned off, and put in place measures to mitigate this risk. We also recommended that Microsoft make the default setting for the collection of diagnostic information from users’ computers “basic” and not “full”. We also called on Microsoft to develop a formal, documented protocol for ensuring that sensitive diagnostic data collected from users will not be used to deliver “tailored experiences.”

For “relevant ads” we recommended that Microsoft clarify that this setting does not involve user consent for Microsoft’s own relevant advertising practices, including a statement directing users to the separate mechanism that would allow them to choose whether and what “relevant ads” they would receive. Further, for “speech recognition”, we recommended that Microsoft allow users to opt in, rather than forcing them to opt out of this feature, and that Microsoft delete any data collected contrary to users’ speech recognition choices.

In response, Microsoft committed to implement a number of changes to address our concerns, beginning with having no pre-selected options for privacy settings during the Windows 10 installation. We are very pleased that users will have the choice to opt in to their desired privacy setting, rather than having to opt out of settings suggested for them. This sets a positive example for other companies wishing to obtain online consent for privacy settings.

Microsoft also committed to:

- enhancing privacy communications;

- augmenting privacy procedures;

- correcting and remediating any data collected contrary to users’ speech recognition choices; and

- implementing measures to mitigate the risks associated with third party apps determining a user’s precise location when the “location” setting is turned off.

In our assessment of the Creator’s Update, we worked closely with our counterparts in the Netherlands. Based on the findings and recommendations flowing from their investigation and those of others, Microsoft made a number of changes to the European version of the software.

Although the Canadian version of Windows 10 is somewhat different, Microsoft’s changes in Europe are relevant and complementary to the findings of our assessment of the operating system. For example, Microsoft has made all settings opt-in, in keeping with our recommendation that users should have to provide explicit consent to send anything more than basic diagnostic information about their computer to Microsoft.

Read the report of findings on the Microsoft investigation.

Facebook: Company agrees to stop using non-users’ personal information found in users’ address books

In June 2013, Facebook notified our Office of a data breach involving contact information uploaded by Facebook users through the site’s Contact Importer tool. A few days later, we received a complaint from an individual alleging that the company collected and disclosed the personal information of Facebook users and non-users without consent.

By way of background, Facebook’s Contact Importer, also known as “Friend Finder,” allows users to upload and store their contacts as part of their Facebook accounts. Facebook uses this information to suggest contacts with which users may want to be friends. It also allows users to send emails inviting contacts who are not on Facebook to sign up for their own account.

In 2012, Facebook engineers developed a process that associates pieces of contact information uploaded by different Facebook users with the same individual. For example, two users may have the same person in their contacts with the same phone number, but with different email addresses. By combining the different bits of contact information uploaded by different users, Facebook can more accurately determine whether a contact being uploaded by a user already has an account, and avoid sending that user an email inviting them to join.

Around the same time in 2012, a different set of Facebook engineers added a new feature to Facebook’s Download Your Information (DYI) tool, enabling users to download a copy of all their imported contacts. However, due to what Facebook called an inadvertent coding error, the DYI tool downloaded too much information.

For each of the user’s contacts, it also downloaded all the information that may have been collected from other users’ address books and matched to that contact. As a result, according to Facebook, additional contact information belonging to some six million users around the world was disclosed, including some 142,000 users in Canada.

In addition, approximately 14 million pieces of contact information (email addresses and telephone numbers) that could not be connected to any Facebook users were also disclosed as a result of the breach. According to Facebook, it did not receive any complaints about misuse of data, nor did it detect any unusual behavior on the DYI tool or Facebook site to suggest wrongdoing or any harm to affected individuals in connection with the coding error.

In collaboration with Ireland’s Data Protection Commissioner, we launched a coordinated investigation focusing on a number of issues raised by the breach, including whether Facebook is obtaining meaningful consent from users and non-users for the use of personal information during the matching process.

We found no issue with the way Facebook allows users to upload their contacts to their Facebook account. We did find, however, that the process of matching across address books constitutes a use of the personal information of users and non-users for which Facebook must obtain meaningful consent. The various notices Facebook offers to users do not include a clear description of the matching process or how it works. In particular, these notices do not explain how a user’s various pieces of contact information, including those imported by other users, will be used in the process of matching across address books.

Facebook disagreed with this finding, submitting that its users are provided with multi-layered notices about the collection and use of personal information in connection with the invite and friend suggestion functions. Moreover, it submitted that users join the platform for the purpose of connecting with friends and with the understanding that helping people connect is the whole point of Facebook.

Informed consent requires an understanding of the purpose, nature and consequences of the collection, use and disclosure of personal information. In this case, Facebook’s use of contact information is aimed at enhancing a core service of connecting people on its social network. After considering Facebook’s submissions, we agreed that, in this specific instance, the company has not changed its purpose for using Facebook users’ contact information; it is simply using the contact information in a different way than historically to serve that purpose. In the circumstances, a user would still generally expect that contact information will be used to make friend suggestions. As a result, our Office concluded the consent issue to be not well-founded.

At the same time, we were not satisfied that Facebook was being sufficiently open with respect to how it handles contact information, especially when explaining how uploaded contacts will be used to help “you and others” find friends. Facebook does not explain what it means by “others.” In this instance, we found the language to be unclear and did not adequately explain the matching process – that is, that Facebook combines and matches the contact information for a particular user with information that has been uploaded by other users.

Facebook advised that, while it respectfully disagreed with our conclusions on this issue, it would revise the notice for the contact import tool and the matching process. Accordingly, our Office determined the concern related to openness to be well-founded and conditionally resolved.

Following the issuance of our findings in this investigation, Facebook provided us with amended notices explaining the address matching process in the Contact Importer tool’s Learn More pages, in the Help Center, on the uploaded contact management page and in its data policy. Our Office is satisfied that these amended notices now adequately explain the address matching process used by Facebook for the purpose of connecting people on its social network.

There was also the matter of Facebook’s use of personal information belonging to non-users that is uploaded by users when they import their contacts to their Facebook account and is used in the matching process by Facebook. The company argued that, when it sends an email inviting a non-user to join, it explains how their information will be used. Again, we found the notice does not really explain how the matching process works. As well, we noted that in sending out the email, Facebook has already used the non-user’s personal information, and has done so without their consent.

Without any workable way to obtain consent from non-users, based on our recommendation, Facebook is no longer keeping the matched contact information of non-users. Facebook has advised that from now on, the process of matching across address books no longer contains associations for contact information that has not been associated with an existing Facebook user, meaning that it is no longer maintaining the matched contact information of non-users. As a result, we determined this issue to be well-founded and resolved.

As part of this investigation, we also worked with Facebook to ensure it was giving users access to all contact information that had been matched to them, as well as the ability to correct this information. Facebook developed a short-term solution to provide users with access to all contact information that had been matched to them and the ability to correct this information. As a result, we determined this issue to be well-founded and resolved.

Facebook also committed to develop a longer-term solution to this issue as part of its efforts to comply with the GDPR. We will continue to engage with Facebook on its efforts in developing such a longer-term solution for users.

Read the report of findings on the Facebook investigation.

Profile Technology: Company’s re-use of millions of Canadian Facebook user profiles violated privacy law

We received complaints from a number of people alleging that their personal information had been collected from old Facebook profiles and groups and used to create new profiles on another social networking site called The Profile Engine without their consent.

The complainants said they discovered their information was posted on The Profile Engine by chance, when conducting internet searches for their own names. In one case, a complainant told us the information on the Profile Engine was lifted from a Facebook profile she had when she was a teenager, pointing out that anyone searching her name ‒ including potential employers ‒ would assume she was a very immature person. Another complainant stated that allegations of assault, which had been originally posted and then removed from Facebook, continued to appear on the Profile Engine.

The respondent, Profile Technology Ltd., argued that, since it was based in New Zealand and had no presence in Canada, our Office did not have jurisdiction to investigate and/or issue a report in this matter. We did not accept those arguments. In our view, there were several factors indicating a real and substantial connection between Profile Technology’s activities and Canada to support our Office’s jurisdiction to investigate the complaints, among others, the company’s own claim that the website had close to 4.5 million Canadian profiles.

In any case, Profile said that it was simply a search engine that allowed people to find information that was already publicly available on Facebook, so consent was not needed. We determined that, while Profile may have originally collected individuals’ profile information from Facebook for the purposes of providing search function services to Facebook users, it later copied and used the information for the new purpose of establishing its own social networking website.

In our view, this exception to consent does not apply since the profile information at issue was not “publicly available” as defined in PIPEDA regulations. Among other things, we considered that, unlike a publication such as a magazine, book or newspaper, Facebook profiles are dynamic and individuals maintain control over their profile information. Over time, users may update and change information, make their profile inaccessible to the general public or even delete their profile altogether. In our view, treating a Facebook profile as a publication would be counter to the intention of the Act, undermining the control users otherwise maintain over their information at the source.

We noted that all of the profiles and group information at issue in the complaints had either been removed from or changed on Facebook. In other words, the information only persisted on the Internet because it appeared on Profile’s website. The profiles collected and re-used by Profile represented a snapshot in time. The company simply copied profiles, posted them on its own site and left them as they were when they were copied.

We determined that Profile had not obtained the individuals’ consent to use their personal information in this way. It was clear to us that a reasonable person would not consider Profile’s use of the information to be appropriate in the circumstances. We recommended that Profile Technology delete all profiles and groups associated with any Canadians, including those associated with the complainants.

Profile refused the above outright. The company’s blatant disregard for privacy obligations, along with their recalcitrance throughout the investigation – often providing cursory responses or failing to respond to our information requests at all – ultimately contributed to a lengthy investigation process into this complex matter.

Before we issued our report of this investigation, the company removed all of the profiles from its website. Since the information could no longer be indexed by search engines, this mitigated a key element of the complaints. However, Profile uploaded much of the information to the Internet (initially on the Internet Archive). The information was uploaded in separate database files with some identifiers removed and/or encrypted, making it widely available in this format for download via peer-to-peer sharing, including on the dark web.

As a result, we have no way of knowing how the data that Profile uploaded to the Internet may be used and disseminated in the future, to the extent that anyone is able to download, recreate the files, and exploit the information for their own purposes. A website operator, for example, could post the information and then charge individuals a fee to take it down, or the information could potentially be used to damage individuals’ reputations.

In an effort to mitigate these kinds of risks, we contacted the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of New Zealand (NZ-OPC) to share our findings and discuss our concerns. The NZ-OPC agreed to review our report and consider what options may be available under the New Zealand Privacy Act and/or whether other New Zealand laws may apply. Our Office will continue to collaborate with our New Zealand counterparts to the full extent allowable under PIPEDA to support any further action to address this issue.

We also contacted Facebook to determine if they could inform our understanding of the database files posted by Profile on the Internet. Facebook confirmed that it was aware of the situation and that it was pursuing various avenues regarding the profile engine information, including via the courts, in relation to a court-recognized settlement.

Read the report of findings on the Profile Technology investigation.

Public Executions: Debtor-shaming website shuts down

The Office received a number of complaints about publicexecutions.com, a website that, for a fee, allowed anyone trying to collect a court-ordered debt payment to post details of the judgment on the site. In addition to posting the name of the debtor and the amount owed on the site, creditors, and anyone else, could post non-verified comments, along with other personal information about the debtor, including the debtor’s address, photographs, or the kind of car they drove. Individuals listed on the website could be searched by name, and, in fact, the complainants’ listings on the site were among top search engine results.

The complainants alleged the website breached their privacy rights under PIPEDA by publishing their personal information without their consent to, in effect, “name and shame” them into paying the debts.

The owner of the website argued that, because there was no “vendor-consumer” relationship with debtors, the disclosure of their personal information was not related to a commercial activity, and thus PIPEDA did not apply. He also argued that the website was a form of journalism, further exempting it from PIPEDA’s consent requirement.

Disclosing an individual’s personal information in exchange for a fee from a third party is clearly a commercial activity, so PIPEDA did apply. As well, we found nothing to support the claim that the site was a form of journalism. A recent Federal Court decision (A.T. v. Globe24h) noted that to be considered journalism, an activity should involve an “element of original production.” There was nothing original about the information on the site; it simply posted content provided by others.

Our Office’s findings took into account the determination of the Ontario Ministry of Government and Consumer Services that the website unlawfully operated as an unregistered “consumer reporting agency” under Ontario’s Consumer Reporting Act. As such, its use and disclosure of information relating to debts owing by individuals was strictly regulated under this legislation.

In this case, the website was disclosing personal information to the world at large. Accordingly, our Office found that, contrary to what is required by subsection 5(3) of PIPEDA, a reasonable person would not consider it appropriate for an organization to broadly publicize this information for financial gain and for the purpose of coercing debtors into paying their debts, given the availability of legal mechanisms to enforce judgments.

The owner of the website rejected our recommendation to delete all information relating to debtors from the website and also have the information removed from search engine caches.

We determined the complaints to be well founded. In light of our inability to order the owner of the website to delete all information from the website, the complaints remained unresolved, and, we were required to use our authority under PIPEDA to initiate legal proceedings with the Federal Court of Canada to have our recommendations enforced.

It was only after these proceedings were initiated that the operator of the website advised our Office that he had taken down the website and had no plans to reinstate it. As a result, our Office withdrew its application with the Federal Court but will continue to monitor to ensure the website is not reinstated in some form.

Read the report of findings on the Public Executions investigation.

Courier company: A company ends “delivery to a neighbour” after consent complaint

In this case, the complainant alleged that the courier company disclosed her personal information without her consent when it delivered a package addressed to her at a neighbour’s house. The package, which the complainant was not expecting, was from a financial institution and contained sensitive financial information.

The company explained that, when a package requires a signature from the addressee and the person is not home, it would either deliver the package to a neighbour or drop it off at a pickup point. It stated that it offers “delivery to a neighbour” because many customers would rather not have to travel to a pickup point to retrieve their package. The company further explained that it obtains consent for delivery to a neighbour through the person or institution that is sending the package.

The company’s terms and conditions for shipping packages mention that, if a package requires a signature, and the addressee is not home, then the courier company could deliver that package to a neighbour of the intended recipient. However, it is not clear that the courier expects the shipper to obtain the addressee’s consent to leave the package with a neighbour.

We contacted the complainant’s financial institution, which advised that it understood that if the addressee was not available to sign for the package, the person would have to pick it up at a store. The financial institution said it didn’t know it was common practice to have a neighbour sign for a package.

We concluded that the courier company did not have the complainant’s consent to have a neighbour sign for and accept the package on her behalf. We also found that the company did not make it clear to shippers how and when a package might be left with a neighbour, nor that the shipper was expected to obtain the addressee’s consent for this.

In response to our recommendation that it ensure valid consent in the future, the company stated that, as of July 2018, it would no longer offer “delivery to a neighbour.” We determined the complaint to be well-founded and resolved, based on the company’s commitment to end delivery to a neighbour. Given that multiple players in the parcel delivery sector use similar neighbour-delivery techniques we encourage all companies to review their practices to ensure compliance with PIPEDA.

Read the case summary on the courier company investigation.

PIPEDA investigations in general

Overview

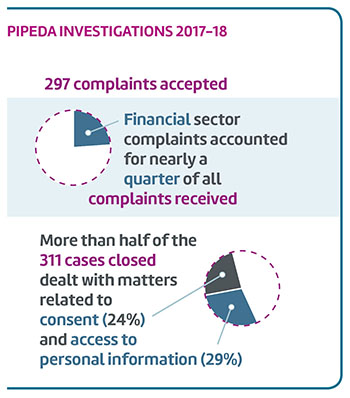

During the 2017-18 fiscal year, we accepted 297 complaints for investigation, and closed 311 investigations.

- As in past years, the financial sector continued to be the subject of most of the complaints we received under PIPEDA. This year, investigations of complaints involving the financial sector accounted for nearly a quarter (24% or 74) of all PIPEDA investigations.

- Organizations in the telecommunications sector (13% or 40), Internet (10% or 32), and services (13% or 39) sectors also attracted significant numbers of complaints.

- Also continuing the trend observed in recent years, Canadians were most likely to complain about issues related to access to their personal information (29% or 86) and consent issues (24% or 70) over the past year. Combined, these accounted for over half of all complaints accepted in 2017-18.

Text version

PIPEDA Investigations 2017-18

297 complaints accepted

Financial sector complaints accounted for nearly a quarter of all complaints received.

More than half of the 311 cases closed dealt with matters related to consent (24%) and access to personal information (29%).

To make the most of our investigative resources, we continue to emphasize the use of early resolution to close straightforward complaints quickly and effectively. This year, two-thirds (66%) of PIPEDA complaints were closed via early resolution.

However, despite these and other successful efforts to increase efficiency, we continued to struggle to keep up with the demand for formal investigations and our backlog of files older than one year continued to grow. At the end of 2017-18, a third of our active investigations (55) were older than 12 months.

A number of factors impact our ability to close investigations within the 12-month timeframe set out in PIPEDA. The ease and low cost with which personal information can be collected, used and shared has reshaped the privacy landscape. The use of big data, AI and other technologies to derive value from raw data continues to grow.

These technologies – barely imaginable when PIPEDA was introduced – can have real and significant impacts on Canadians’ privacy. More and more investigations require extensive technological analyses to first assess the privacy issues and then develop meaningful recommendations. Our investigation into a consent complaint about Microsoft Windows 10 described earlier in this report is just one example.

Our investigations are further complicated by the need to understand and remain current with the increasingly complex and fluid business models made possible by technology and data monetization.

Because our current model does not permit us to be selective as to which complaints merit investigation within our limited resources, these new complex issues must be investigated along with all other complaints that cannot be resolved to complainants’ satisfaction through early resolution. In addition, without the backdrop of powers to order changes or sanction organizations with penalties for non-compliance, organizations can be slow to respond to our investigative inquiries and equally slow to commit to taking corrective action.

Other PIPEDA investigations

As demonstrated by the investigations summarized previously, technology has created a host of challenges for consenting to the collection, control and use of our personal information. Technology has also created new challenges for safeguarding personal information from unauthorized disclosure. PIPEDA requires that organizations protect the personal information they hold with safeguards proportionate to the sensitivity of the information – the more sensitive the information, the higher the level of protection that should be in place.

In the digital world, security cannot be a one-time thing. Safeguards must be reviewed on an ongoing basis to ensure sensitive information is protected from new and emerging threats.

PIPEDA doesn’t specify what safeguards must be used, so it is up to organizations to identify the appropriate physical, technological and/or organizational tools necessary to ensure adequate protection of personal information. However, as the following investigation summaries demonstrate, in the digital world, security cannot be a one-time thing. Safeguards must be reviewed on an ongoing basis to ensure sensitive information is protected from new and emerging threats.

WADA: Agency improves deficient security measures for protecting athletes’ personal information following investigation of global breach

As noted in last year’s Annual Report, in September 2016, our Office became aware of a breach of the Montreal-based World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), which oversees the international anti-doping regime for amateur sports. Specifically, a group publically known as “Fancy Bear” disclosed on its website and elsewhere, the names of certain athletes who had competed in the 2016 Rio Olympic Games, along with their personal information which had been ex-filtrated from the Anti-Doping Administration and Management System (ADAMS).

To provide proper context and possible motive for this breach, it is important to highlight the dramatic events which occurred in the lead-up to the 2016 Rio Olympic Games. In July 2016, WADA released the findings of an independent investigation which confirmed certain allegations of Russian State manipulation of the doping control process at the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympic Games.Footnote 1 Russian whistleblowers had alleged state involvement in a massive doping operation in Russia, something that Russia has vehemently denied. Subsequently, the 2016 Rio Olympic Games took place from August 5 until August 21, 2016 and 118 Russian athletes were banned from competing.

Based on our investigation, it appeared the attack began with a phishing campaign: emails that appeared to be from WADA’s Chief Technology Officer were sent to WADA employees, which compromised three WADA email accounts. Subsequently, the attackers gained access to an ADAMS administrator account and began using it to access information over the course of the next several days.

There can be no argument that much of the personal information contained in ADAMS is highly sensitive. The information consists of personal health information in the form of medical conditions, medications and prescriptions, analyses of bodily specimens and even genetic information outlined in an athlete’s biological passport. In addition, ADAMS also contains anti-doping rule violations and information about an athlete’s whereabouts.

The potential harms associated with the breach of this information are substantial and multi-fold. Unauthorized access and disclosure of certain personal health information can cause stigmatization, discrimination and psychological harm to individuals. The release of adverse analytical findings which, for legitimate reasons, have not otherwise been made public can cause embarrassment and shame to athletes, greatly impacting their reputation, image and personal and professional livelihoods.

All this suggests that in designing its safeguards, WADA must take into account the value of the information it holds to those who may seek to acquire it through nefarious means, and the prospect that it will continue to be the target of sophisticated attacks. It is noted that certain public reports have linked the Fancy Bear group to state-involved hacking efforts.

At the time of the breach, WADA had in place certain technological, physical and organizational safeguards. That said, there clearly were significant failings and their safeguard environment fell well below the level expected of an organization responsible for holding such highly sensitive medical information, with the potential to inflict significant damage on the reputation and integrity of athletes and the Olympic movement as a whole. WADA’s need for an adequately robust safeguard framework is further informed by its status as a potential “high-value” target, for attacks by sophisticated hackers, including those of a state-sponsored nature.

In our preliminary report, our Office recommended that WADA augment its security safeguards to an appropriate level to protect the security and confidentiality of the sensitive personal information under its control by:

- developing a comprehensive information security framework which incorporates written policies and procedures to ensure that possible risks have been addressed;

- implementing appropriate safeguards related to access controls;

- employing adequate encryption protocols for ADAMS data in their custody;

- ensuring that application security and intrusion detection is properly configured and that systems and logs are adequately and actively monitored.

In response to our preliminary report, WADA agreed to implement all of the recommendations and accordingly, we concluded that the matter is well-founded and conditionally resolved. As such, our Office will be closely monitoring the organization’s implementation of our recommendations and, to this end, has entered into a compliance agreement with WADA.

VTech: Toy-maker’s failure to patch well-known vulnerability leads to massive data breach

In early December 2015, VTech Holdings Limited, a Hong Kong-based manufacturer of web-enabled electronic learning toys for children, notified our Office of a global data breach. According to the company, the personal information of over 300,000 children in Canada alone may have been compromised, including their names, dates of birth, photographs, voice recordings and chat discussions. VTech stated that the personal information of some 237,000 Canadian adults – mostly parents of the children affected – could also have been compromised.

Shortly after this notification, a Canadian affected by the breach filed a complaint with our Office. The complainant alleged that VTech failed to adequately safeguard the personal information of its customers, allowing hackers to access customers’ information, possibly including his own and his son’s.

The investigation, which benefited from collaboration with our international counterparts, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission and the Hong Kong Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data, found that the hacker accessed one of VTech’s networks using SQL injection. This is a well-known and commonly exploited security vulnerability.

The investigation also revealed that, among other shortcomings, VTech did not test for vulnerabilities on a regular basis and, as a result, had not taken any action to protect its networks from this easily preventable attack.

VTech did act quickly to minimize the impact of the breach, notifying its customers by email and other methods and advising them of steps they could take to reduce the risk to their personal information. The company also committed to implementing a variety of measures to upgrade the security of its networks and safeguard its customers’ personal information.

Accordingly, we found this complaint to be well-founded and resolved.

We note that, while this breach caused considerable concern and worry for VTech customers, including hundreds of thousands of Canadians, it is possible that very little personal information was compromised. The hacker, who was arrested, claimed he intended only to expose vulnerabilities in VTech security and had shared only a small amount of information with a reporter to show how easily he could access VTech’s networks. The information that was disclosed was returned to the company.

Read the report of findings on the VTech investigation.

Access and airlines

Our Office also had the opportunity to investigate the treatment of access requests by airlines in two separate cases related to the disclosure of personal information by the airlines to third parties.

Jet Airways: Commissioner does not have authority under PIPEDA to compel documents subject to solicitor-client privilege claim