Projecting our values into laws

Laying the foundation for responsible innovation

2020-2021 Annual Report to Parliament on the Privacy Act and the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

30 Victoria Street

Gatineau, Quebec K1A 1H3

© Her Majesty the Queen of Canada for the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, 2021

ISSN 1913-3367

Letter to the Speaker of the Senate

December 9, 2021

The Honourable George J. Furey, Senator

The Speaker

Senate of Canada

Ottawa, Ontario

K1A 0A4

Dear Mr. Speaker:

I have the honour to submit to Parliament the Annual Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, for the period from April 1, 2020 to March 31, 2021. This tabling is done pursuant to sections 38 for the Privacy Act and 25 for the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act. Within the aforementioned, the Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada entitled Review of the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada is included. This tabling is done pursuant to section 72(2) of the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act.

Sincerely,

Original signed by

Daniel Therrien

Commissioner

Letter to the Speaker of the House of Commons

December 9, 2021

The Honourable Anthony Rota, M.P.

The Speaker

House of Commons

Ottawa, Ontario

K1A 0A6

Dear Mr. Speaker:

I have the honour to submit to Parliament the Annual Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, for the period from April 1, 2020 to March 31, 2021. This tabling is done pursuant to sections 38 for the Privacy Act and 25 for the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act. Within the aforementioned, the Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada entitled Review of the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada is included. This tabling is done pursuant to section 72(2) of the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act.

Sincerely,

Original signed by

Daniel Therrien

Commissioner

Commissioner’s message

Annual Reports present an opportunity to take stock of the past year, and to highlight both progress made and challenges that persist within the broader context of what we have been trying to achieve.

Over the course of my mandate, it has become increasingly clear that we need a stronger privacy framework to protect the rights of Canadians in an increasingly digital world. This would allow Canadians to safely participate in the digital economy and confidently embrace new technologies.

I wish I could begin this Annual Report to Parliament by stating that this has been achieved, with contemporary privacy laws fit for the digital age firmly in place to adequately protect Canadians. Unfortunately, we are not there yet, although I can report that on some issues we did make important progress.

There is no person or industry that was not affected by the pandemic in some way. At the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC), we adapted smoothly to work-from-home and maintained all our services. Several of the privacy issues we tackled involved initiatives related to COVID-19.

Despite the fact that we were still in the midst of the pandemic, 2020 marked a milestone for privacy law in Canada.

Following calls to action over the course of many years by my office, industry stakeholders and civil society, the government finally tabled Bill C-11 to overhaul Canada’s federal private sector privacy law. It also put forward a comprehensive public consultation document aimed at modernizing our 40-year-old public sector law. While proposed reforms did not progress into new laws before the election called in August, I welcome what is hopefully only a brief pause as a sign of reflection. On the private sector side in particular, significant amendments were needed to ensure the rights and values of Canadians are adequately protected. It is my hope that in the coming months we will see the introduction of a revised private sector law as well as legislative proposals to update the public sector act.

I was deeply concerned that Bill C-11, which died on the order paper when the election was called, would be a step backwards. With the opening of a new Parliament, I am hopeful that the government will make some of the changes we have proposed and we look forward to working with them on legislative reform.

Although the future of privacy protection in Canada remains unsettled and the issues we are facing are complex, I believe the road ahead is quite clear.

As a society we must project our values into the laws that regulate the digital space. Our citizens expect nothing less from their public institutions. It is on this condition that confidence in the digital economy, damaged by numerous scandals, will return.

Evolution of privacy in recent years

To know where we are going, it is useful to remember where we have been and to look at trends we are seeing, for example, in terms of state surveillance, surveillance capitalism and public-private partnerships.

There’s no doubt the privacy landscape has shifted since I began my mandate as Commissioner in 2014. Top of mind back then was the Edward Snowden revelations on how national security practices of governments could intrude into the lives of ordinary citizens. “Privacy is dead,” was also a familiar refrain at that time.

Today, the privacy conversation is dominated by the growing power of tech giants like Facebook and Google, which seem to know more about us than we know about ourselves. Terms like surveillance capitalism and the surveillance economy have become part of the dialogue.

After 9/11, Canada and its allies enacted many laws and initiatives in the name of national security. Some of these laws went too far. The Arar inquiry, Snowden affair and reports involving metadata collection by the Communications Security Establishment (CSE) and the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) reminded us that clear safeguards are needed to protect rights and prevent abuse.

Fortunately, after healthy democratic discussions, we have seen improvements. New oversight bodies were introduced, as were amendments to national security legislation to ensure more appropriate thresholds are in place before personal information can be collected or shared between security agencies or law enforcement bodies.

But while we have seen state surveillance modulated to some extent, the threat of surveillance capitalism has taken centre stage. Personal data has emerged as a dominant and valuable asset and no one has leveraged it better than the tech giants behind our web searches and social media accounts.

The risks of surveillance capitalism were on full display in the Facebook/Cambridge Analytica scandal that is now the subject of proceedings in Federal Court because my office did not have the power to order Facebook to comply with our findings and recommendations, nor issue financial penalties to dissuade this kind of corporate behaviour.

The newest frontier of surveillance capitalism is artificial intelligence (AI). AI has immense promise in addressing some of today’s most pressing issues, but must be implemented in ways that respect privacy, equality and other human rights. Our office’s investigation of Clearview AI’s use of facial recognition technology was an example of where commercial AI deployment fell significantly short of privacy laws.

Digital technologies like AI, that rely on the collection and analysis of personal data, are at the heart of the fourth industrial revolution and are key to our socio-economic development. However, they pose major risks to rights and values.

To draw value from data, the law should accommodate new, unforeseen, but responsible uses of information for the public good. But, due to the frequently demonstrated violations of human rights, this additional flexibility should come within a rights-based framework.

Another trend we are seeing is an increase in public-private partnerships and the use of corporate expertise to assist the functioning of the state. Our investigations of Clearview AI and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) this past year are prime examples. Clearview AI violated the private sector privacy law by creating a databank of billions of images scraped from the internet without consent in order to drive its commercial facial recognition software. Our Special Report to Parliament tabled last June highlighted that a federal government institution, such as the RCMP, cannot collect personal information from a third-party agent like Clearview AI if that third-party agent collected the information unlawfully.

Privacy issues arising from public-private partnerships were also evident in a number of government-led pandemic initiatives involving digital technologies this past year. These issues underscored the need for more consistency across the public and private sector laws.

Progress on privacy priorities

While the privacy landscape has certainly evolved in the past few years, the strategic priorities we identified back in 2015, following significant public consultations, have remained relevant and useful in terms of guiding and focusing our efforts.

The 4 priorities we identified were:

- The Economics of personal information;

- Government surveillance;

- Reputation and privacy; and

- The body as information.

Equally important were the 5 strategies we said we would employ to advance them: exploring innovative and technological ways of protecting privacy; strengthening accountability and promoting good privacy governance; protecting Canadians’ privacy in a borderless world; enhancing our public education role; and enhancing privacy protection for vulnerable groups.

The vision behind the priorities was an admittedly ambitious goal in the age of big data: to increase the control Canadians have over their personal information.

We wanted to better understand privacy in each of these areas, and in turn, to inform organizations and the public of the issues at stake, to influence behaviour and to use our regulatory powers most effectively.

Several years on, I remain convinced that our identified priorities were the right ones for these times when massive amounts of personal information are being collected, and powerful algorithms are being used to detect patterns for purposes that range from marketing to national security.

My office can be proud of the important work completed under each of our priority banners. We have made some progress – more so on some priorities than others.

Ultimately, our efforts were limited by the tools at our disposal. In each of the 4 areas of strategic focus, we saw again and again that the real solution to protecting rights is through the modernization of federal privacy laws.

Below, we offer some examples of what we have advanced in each area.

Strategic privacy priority: The economics of personal information

Our goal under the economics of personal information was to enhance the privacy protection and trust of individuals so that they may confidently participate in an innovative digital economy. The centerpiece of our work in this area were our Guidelines for obtaining meaningful consent.

We have also produced guidance on “no go zones” for the collection, use and disclosure of personal information. In it, we outline a number of practices that would be considered “inappropriate” by a reasonable person, including personal information practices that involve profiling or categorization that leads to unfair, unethical or discriminatory treatment, contrary to human rights law.

We have also conducted investigations that address this strategic priority. While these cases have helped to raise awareness of privacy issues, they have also demonstrated the severe limitations of existing laws.

Case in point: our 2019 investigation into the Facebook/Cambridge Analytica scandal. The investigation found Facebook, despite its detailed privacy policies, had failed to obtain meaningful consent and failed to take responsibility for protecting the personal information of Canadians. Despite its public acknowledgement of a “major breach of trust,” Facebook disputed the findings and refused to implement recommendations to address deficiencies.

This case demonstrates the weakness of the current law in forcing companies to be accountable and makes plain that Canadians cannot rely exclusively on companies to manage their information responsibly.

Our investigation of technology company Clearview AI also revealed some of the shortcomings in our law.

We, along with 3 provincial counterparts, found that Clearview AI’s scraping of billions of images of people from across the Internet represented mass surveillance and was a clear violation of the privacy rights of Canadians.

The investigation found that Clearview AI had collected highly sensitive biometric information without the knowledge or consent of individuals. Furthermore, Clearview AI collected, used and disclosed Canadians’ personal information for inappropriate purposes, which cannot be rendered appropriate via consent.

Despite our findings, the company continued to claim its purposes were appropriate, citing the requirement under federal privacy law that its business needs be balanced against privacy rights. We have urged Parliamentarians to ensure a new federal law stipulates where there is a conflict between commercial objectives and privacy protection, Canadians’ privacy rights should prevail.

Our goal was to increase consumer confidence, however, it is clear that we continue to see a crisis of trust. Polling tells us that the vast majority of Canadians are very concerned about their inability to protect their privacy and trust levels remain low.

Canadians want to enjoy the benefits of digital technologies, but they want to do it safely. To make real progress, we need to improve our privacy laws. It is the role of government, and Parliament, to give Canadians the assurance that legislation will protect their rights.

This past year, with significant research and submissions to government and Parliament on both the public and private sector laws, we strongly advocated for better legislation to protect Canadians.

Strategic privacy priority: Government surveillance

Our goal for this priority was to contribute to the adoption and implementation of laws and other measures that demonstrably protect both national security and privacy.

As mentioned earlier, government surveillance occupied much of our energy in the early part of my mandate. We have provided advice to government aimed at achieving national security and public safety with measures that appropriately protect privacy rights.

We also called for greater oversight and were pleased to see Bill C-22 introduce the National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians, and Bill C-59 create a new expert national security oversight body, the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency (NSIRA). Since its inception, we have regularly engaged with NSIRA, for example, on a collaborative review under the Security of Canada Information Disclosure Act (SCIDA), which is anticipated to conclude with a report to be tabled later this year.

We have advised the RCMP on its use of drones and body-worn cameras, and we provided advice to the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) and the public on electronic device searches at border crossings.

This past year, and as detailed in the following pages, we saw a welcome rise in requests for consultations on national security and public safety issues. We continue to advise the government on these matters, for example in relation to the Passenger Protect Program.

Also, when it comes to government surveillance, we made a series of recommendations to Statistics Canada following our investigation into its plans to collect highly detailed financial information about individuals.

The initiatives involved the collection of credit histories and the proposed mass collection of line-by-line financial transaction information from banks without the knowledge or consent of affected individuals.

We found the program’s design raised significant privacy concerns and illustrated the interdependence of privacy, trust, and social acceptance. Importantly, it highlighted the inadequacy of existing legislation insofar as it lacks the necessity and proportionality standard that exists in other privacy laws around the world.

Necessity and proportionality means organizations should only pursue privacy-invasive activities and programs where it is demonstrated that they are necessary to achieve a pressing and substantial purpose and where the intrusion is proportional to the benefits to be gained.

During the investigation, Statistics Canada officials spoke about their objectives, but did not demonstrate the necessity of collecting so much highly sensitive information about millions of Canadians.

While we welcomed the agency’s willingness to redesign the initiatives to respect the principles of necessity and proportionality, this is not currently a legal requirement. We have also called for amendments to the Privacy Act to expressly include a necessity and proportionality requirement for the collection of personal information.

Strategic privacy priority: Reputation and privacy

Our intention with this priority was that we would help create an online environment where individuals may use the Internet to explore their interests and develop as persons without fear that their digital trace will lead to unfair treatment.

A key ongoing initiative related to this priority is our Draft Position on Online Reputation, which we developed after a consultation and call for essays from various stakeholders. The Draft Position highlighted the OPC’s preliminary view on existing protections in our private-sector privacy law, which includes the right to ask search engines to de-index web pages that contain inaccurate, incomplete or outdated information and removal of information at the source. The Draft Position also emphasized the importance of education to help develop responsible, informed online citizens.

In 2018, we filed a Reference with the Federal Court seeking clarity on whether Google’s search engine service is subject to federal privacy law when it indexes web pages and presents results in response to a search for a person’s name. We asked the Court to consider the issue in the context of a complaint involving an individual who alleged Google was contravening the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) by prominently displaying links to online news articles about him when his name was searched.

The Federal Court issued its decision on the merits of the Reference questions in July 2021. We welcomed the Court’s decision, which aligned with our position that Google’s search engine service is collecting, using, and disclosing personal information in the course of commercial activities, and is not exempt from PIPEDA under the journalistic exemption.

Since it is ultimately up to elected officials to confirm the right balance between privacy and freedom of expression in our democratic society, our preference would be for Parliament to clarify the law in this regard. For the time being, in the absence of such clarification in the legislation, we will continue our investigations.

Strategic privacy priority: The body as information

With this priority, we wanted to promote respect for the privacy and integrity of the human body as the vessel of our most intimate personal information.

We have issued draft guidance for police on the use of facial recognition technology as well as guidance for individuals on smart devices and wearable technologies. In cooperation with our international counterparts as part of the Global Privacy Enforcement Network, we also conducted a sweep of Internet-connected health devices, such as fitness trackers and sleep monitors, and found many such devices fall short on privacy.

We have provided advice to individuals and developed guidance for businesses on direct-to-consumer genetic testing and intervened before the Supreme Court of Canada to defend the position that individuals should not be compelled to disclose their genetic test results to an employer or insurance company or any other business. We welcomed the Court’s decision to uphold the constitutionality of the Genetic Non-Discrimination Act.

Without question, the global pandemic has also shone a light on this priority. Among other activities, over the past year we advised government on and monitored the implementation of various contact-tracing initiatives, including the COVID Alert app. Along with our provincial and territorial counterparts, we offered privacy advice on vaccine passports.

As mentioned, we also investigated and prepared guidance on the use of facial recognition technology. Our investigations into Clearview AI and the RCMP’s use of the company’s facial recognition technology demonstrate that significant gaps remain in appropriately protecting this highly sensitive information. At present, the use of facial recognition technology is regulated through a patchwork of statutes and case law that, for the most part, do not specifically address the risks posed by the technology. This creates room for uncertainty concerning what uses of facial recognition may be acceptable, and under what circumstances. The path forward is uncertain but as part of our ongoing consultation on guidance for police use of facial recognition, we have been engaging with police, civil society and other stakeholders on important questions surrounding the use of this technology, including whether the current legal framework needs to change.

Next steps

The strategic priorities that have helped to guide our work remain extremely relevant today. We have made some headway, but our ultimate objective of restoring Canadians’ trust in government and the digital economy remains elusive. Indeed, that goal will remain out of reach until the government enacts new federal laws that appropriately protect privacy rights in Canada.

I remain fully committed to ensuring we achieve this urgent goal.

2020-21, a year of collaboration

As we compiled the content for this Annual Report, I was struck by the degree of collaboration reflected in its pages and I think this is an area where we made important progress.

Collaboration is critical to increasing privacy awareness and compliance. Over the past year, we were increasingly proactive in reaching out to, and bridging relationships with, federal institutions, our provincial, territorial and international privacy counterparts, the business community, civil society and individuals.

In the last year alone, we provided advice to government institutions through advisory consultations more than 130 times, a significant increase over past years.

We also provided advice to businesses, for example, through 13 advisory engagements. Our consultations with businesses have demonstrated that privacy is not an impediment to public health, other government objectives or business interests. The key is good design, which ensures that all of these interests can be achieved concurrently.

On the investigative side, we collaborated with our provincial colleagues on an unprecedented number of joint investigations, including our first-ever joint investigation with all provinces with substantially similar legislation. We also jointly produced guidance on several important topics, including vaccine passports and facial recognition.

We also saw a high degree of collaboration on the international front. We continue to lead in the area of international enforcement collaboration, including in our co-chair roles for the Global Privacy Assembly’s International Enforcement Cooperation Working Group and its Digital Citizen and Consumer Working Group, the latter focused on fostering greater cross-regulatory cooperation across the privacy, competition and consumer protection spheres. More detail on our international work and its impact is found later in this report.

Meanwhile, in conjunction with Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission and the Competition Bureau, we issued advice to the mobile app industry in relation to their obligations under anti-spam legislation. As mentioned earlier, we also had an opportunity to work collaboratively on issues of mutual interest with the NSIRA.

As I noted earlier, protecting privacy in a borderless world was one of the approaches we recognized as being essential to advancing privacy priorities for Canadians in a global economy. Ideally, maximizing collaborations would be facilitated by interoperable laws, domestically and internationally. This is an essential way forward and a trend that must not only continue, but grow.

What’s next

At the time of writing this report, my mandate as Privacy Commissioner was extended for a year. This will be an important transition period, both for law reform and for the OPC as an institution. I appreciate having the opportunity to continue advising Parliament and working with the talented and deeply devoted OPC staff to prepare for a new era in privacy protection.

The plan for Privacy Act (the public sector privacy law) reform looks promising, and I hope to see a bill tabled soon in Parliament. Meanwhile, I am hopeful the government will seriously consider needed improvements to Bill C-11, so that we can see an updated private sector privacy law that more effectively achieves responsible innovation and the protection of rights.

Once new laws are in place, we anticipate becoming a substantially different Office of the Privacy Commissioner – notably one with greater enforcement powers and an enhanced role in developing guidance, approving codes of practice and working with public- and private-sector institutions towards greater respect for privacy rights.

While it will likely take some time, perhaps a few years, before the OPC exercises new duties, I think it is important that we start preparing as soon as possible, so that we are fully effective when new laws come into force. This planning exercise will be conducted with a view to being even more transparent and fair towards regulated entities and other stakeholders. We want to deepen our engagement activities. The role of a regulator like the OPC is first and foremost to help organizations comply with the law; and when enforcement is required, to exercise this authority quickly but fairly.

This is an important moment for the future of privacy protection in Canada and these are certainly exciting times for the OPC. I am proud of the work we have done to get us to this pivotal point, but there is much more that needs to be done. I look forward to the ongoing collaboration with our many partners in the year to come, to continuing to advocate for Canadians’ privacy rights, for responsible innovation and to helping lay the foundation for what comes next.

Legislative reform: for effective privacy protection, responsible innovation and strengthened consumer trust

By the end of 2020, Canada had marked a pivotal moment for privacy law.

In rapid succession, the federal government unveiled both Bill C-11, which sought to overhaul the federal private sector law, as well as a comprehensive public consultation laying out a plan for modernizing Canada’s nearly 40-year-old public sector law.

These developments followed years of persistent calls for action from our office, as well as stakeholders from across industry and civil society. It has been clear for many years that Canada’s 2 federal privacy laws are not suited to the task of protecting privacy rights in a digital world. We need to better protect Canadians at a time when their confidence in the digital economy is needed to fuel a post-pandemic economic recovery.

The government’s plans for a way forward hit the mark on some fronts, but not others. We were quite pleased with Privacy Act public sector reform proposals contained in a Department of Justice discussion paper. However, the government also introduced Bill C-11, which died on the Order Paper when a federal election was called in August 2021. As imperfect as that bill was, we believe it is possible to bring substantial improvements to the legislation within its existing structure and without having to start over from scratch.

This chapter outlines some of our office’s main concerns and recommendations related to Bill C-11, as well as our substantially more positive submission to the Department of Justice consultation on reform of the Privacy Act.

It also provides an overview of our consultation on regulating artificial intelligence (AI), a key question related to both federal laws, as AI technology holds immense promise but can also have serious consequences for privacy. Further, it discusses a clear gap in the legislative framework for Canadians’ privacy protection, in light of a complaint against 3 federal political parties.

Finally, we provide a summary of our submission to a government review of the Access to Information Act.

Bill C-11 needs significant amendments

In November 2020, the Government of Canada tabled Bill C-11, an important and concrete step toward modernizing our federal private sector legislation. The bill, which died on the Order Paper when a federal election was called in August, would have enacted the Consumer Privacy Protection Act and the Personal Information and Data Protection Tribunal Act.

After several months of internal analysis by the OPC, in May 2021, Commissioner Therrien shared his submission and research on the legislative proposal with the House of Commons Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics.

He noted to Parliament how the bill was misaligned and less protective than the laws of other jurisdictions in a number of ways. He called it a step backward overall. Bill C-11 did not include the privacy protective measures that exist in other countries with similar economies or even in the privacy laws of some provinces in Canada.

Of particular concern if adopted, the bill would have given consumers less control and organizations more flexibility in monetizing personal data, without increasing their accountability. Meanwhile, the proposed penalty scheme was unjustifiably narrow and protracted.

The Commissioner also noted that the OPC would be subject to several new constraints and limitations, when in fact the OPC needs more flexible tools to achieve its mandate in a global, complex and rapidly evolving environment.

He stressed that privacy is not an impediment to economic innovation or technological adaptation. On the contrary, data protection legislation that effectively safeguards privacy and ensures trust can contribute to economic growth. Modernized effective legal regimes achieve this by providing consumers with confidence that their rights are respected. Many countries with strong privacy laws are also leaders in innovation.

The submission set out 60 recommendations aimed at enhancing the bill’s privacy protections for Canadians while enabling responsible innovation for businesses. The recommendations were grouped under 3 over-arching themes:

- Achieving a more appropriate weighting of privacy rights and commercial interests;

- Establishing specific rights and obligations; and

- Ensuring access to quick and effective remedies and the role of the OPC.

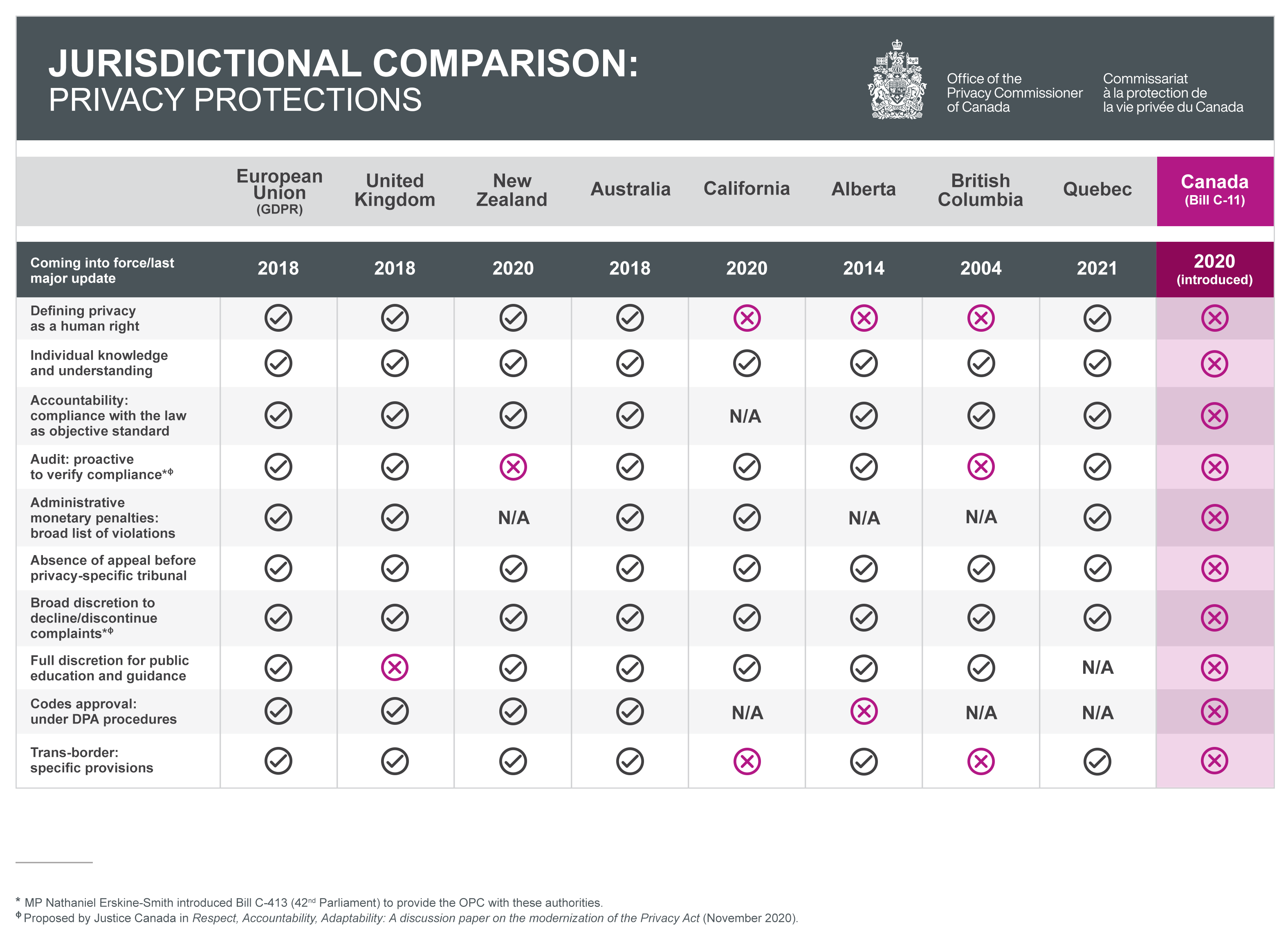

Jurisdictional Comparison: Privacy protections

Text version of Figure 1

| European Union (GDPR) |

United Kingdom | New Zealand | Australia | California | Alberta | British Columbia | Quebec | Canada (Bill C-11) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coming into force/last major update | 2018 | 2018 | 2020 | 2018 | 2020 | 2014 | 2004 | 2021 | 2020 (introduced) |

| Defining privacy as a human right | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Individual knowledge and understanding | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Accountability: compliance with the law as objective standard | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Audit: proactive to verify compliance*,** | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Administrative monetary penalties: broad list of violations | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | No |

| Absence of appeal before privacy-specific tribunal | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Broad discretion to decline/discontinue complaints*,** | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Full discretion for public education and guidance | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | No |

| Codes approval: under DPA procedures | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | No | N/A | N/A | No |

| Trans-border: specific provisions | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| * MP Nathaniel Erskine-Smith introduced Bill C-413 (42nd Parliament) to provide the OPC with these authorities. | |||||||||

| ** Proposed by Justice Canada in Respect, Accountability, Adaptability: A discussion paper on the modernization of the Privacy Act (November 2020). | |||||||||

Key issues to consider when designing a modern law

Digital technologies that rely on the collection and analysis of personal information are at the heart of the fourth industrial revolution and are key to our socio-economic development. They can serve the public interest, if properly designed.

But they can and have also disrupted rights and values that have been centuries in the making: fundamental rights such as privacy, equality and democracy.

In our view, if Canadian laws are to be fit for purpose in these modern times, they must address the following:

Issue 1: Defining permissible uses

The challenge is to define permissible uses of data so as to both enable responsible innovation and protect the rights and values of citizens.

Our private sector law, PIPEDA, is currently based on the consent model. Consent has its place in data protection, if truly meaningful and in relatively straightforward business relationships between organizations and consumers, but it cannot be the only means of protecting privacy. In fact, consent can be used to legitimize uses that are objectively completely unreasonable and contrary to our rights and values. And refusal to provide consent can sometimes be a disservice to the public interest.

Bill C-11 rightly introduced certain exceptions to consent, giving businesses greater flexibility in the processing of personal information. Unfortunately, some of the exceptions were too broad or ill-defined to foster responsible innovation.

As suggested in the recommendations we issued on artificial intelligence last fall, we could authorize the use of data for legitimate business interests, but within a rights-based framework.

Such a provision would give considerable flexibility to use data for new purposes unforeseen at the time of collection, but would be based on the particular and knowable purposes being pursued by the organization, and subject to regulatory oversight.

What we need is not Bill C-11’s model of self-regulation (where vaguely worded legal standards are left to be clarified by commercial organizations and the role of regulators would be severely limited) but true regulation, meaning objective and knowable standards adopted democratically, enforced by democratically appointed institutions, like the Office of the Privacy Commissioner.

We need sensible legislation that allows responsible innovation that serves the public interest and is likely to foster trust, but that prohibits using technology in ways that are incompatible with our rights and values.

Issue 2: The need for a rights-based framework

The greater flexibility to use personal information without consent for responsible innovation and socially beneficial purposes should occur within a legal framework that would entrench privacy as a human right and as an essential element for the exercise of other fundamental rights.

Only a rights-based law can provide adequate protection, not from theoretical risks to privacy, but from the kind of actual harms we’ve seen time and time again in Canada and abroad.

Unfortunately, Bill C-11 assumed that privacy and commercial interests are competing interests and that a balance must be struck between the two. In fact, it arguably gave more weight to commercial interests than the current law by adding new commercial factors to be considered in the balance, without any reference to the lessons of the past 20 years on technology’s disruption of rights.

In our view, it would be normal and fair for commercial activities to be permitted within a rights framework, rather than placing rights and commercial interests on the same footing. Generally, it is possible to concurrently achieve both commercial objectives and privacy protection. However, where there is conflict, rights should prevail.

In adopting a rights-based approach, we would send a powerful message as to who we are and what we aspire to be as a country. This is the approach adopted in Quebec and the approach suggested in recent proposals for law reform by the Government of Ontario.

That being said, some have argued that a rights-based framework is not possible in a federal law in Canada due to our Constitution.

We agree that the principal basis for a federal private sector privacy law is Parliament’s jurisdiction over trade and commerce. However, if the law is in pith and substance about regulating trade and commerce, then it can include privacy protections, including privacy as a human right. Indeed, recent jurisprudence from the Supreme Court of Canada shows that a preamble would strengthen the constitutional footing of the legislation by identifying the purpose and background to the legislation.

Recognizing privacy as a human right is also fully compatible with our existing technology-neutral, principles-based data protection framework and it need not result in a law that is overly prescriptive.

The prescriptive nature of a law is often related to the level of detail associated with the definition of specific privacy principles. A rights-based framework operates at the same level of generality as a principles-based law. Neither is strictly prescriptive. They are both equally flexible and adaptable to regulate a rapidly changing environment such as the world of technology and the digital economy.

The bottom line is that commercial activities should be permitted within a rights framework, rather than placing rights and commercial interests on the same footing.

Our 2021 investigation into Clearview AI is a good example of what can go wrong when this important principle is ignored.

Clearview AI: Striking an appropriate balance between privacy rights and commercial interests

In February 2021, our office, along with 3 provincial counterparts, released the results of an investigation into technology company Clearview AI, which sells a facial recognition tool that allows law enforcement to match photographs of unknown people against a massive databank of 3 billion images, scraped from the Internet.

In Canada, this data was primarily used for policing purposes without the knowledge or consent of those involved. The result was that billions of people essentially found themselves in a police line-up. We concluded this represented mass surveillance and was a clear violation of PIPEDA.

Clearview AI put forward a series of arguments based on PIPEDA’s approach that privacy rights and commercial interests must be balanced against one another. It claimed that individuals who placed or permitted their images to be placed on the Internet lacked a reasonable expectation of privacy in their images, that the information was publicly available and that the company’s appropriate business interests and freedom of expression should prevail.

Although we rejected these arguments, some legal commentators have suggested our findings may be inconsistent with PIPEDA’s purpose clause by not giving sufficient weight to commercial interests. If Bill C-11 had been passed as tabled, Clearview AI and these commentators could still have made such arguments.

We argued that Bill C-11 should be amended to make clear that, where there is a conflict between commercial objectives and privacy protection, the latter should prevail.

Further Reading

- Joint investigation of Clearview AI, Inc. by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, the Commission d’accès à l’information du Québec, the Information and Privacy Commissioner for British Columbia, and the Information Privacy Commissioner of Alberta, February 2, 2021

- Statement by the Privacy Commissioner of Canada following an investigation into Clearview AI, February 3, 2021

Issue 3: How to define corporate accountability

Accountability is one of the primary counter-balances to increased ability for organizations to use information without consent. Given this, we believe it is critical that the accountability principle be clearly defined in the law and that the legislation provide protective measures such that the accountability of organizations is real and demonstrable.

The Consumer Privacy Protection Act as drafted failed to define accountability as an objective standard requiring policies and procedures that ensure compliance with the law. Instead, it defined accountability in descriptive terms, akin to self-regulation: the adoption of policies and procedures that an organization decides to put in place.

It also importantly failed to provide for demonstrable accountability, meaning accountability that is demonstrated to the regulator, an independent third party. In today’s world where business models are opaque and information flows are increasingly complex, individuals are unlikely to file a complaint when they are unaware of a practice that may harm them. This is why it is so important for the regulator to have the authority to proactively inspect the practices of organizations. Where consent is not practical and organizations are expected to fill the protective void through accountability, these organizations must be required to demonstrate true accountability upon request.

Bill C-11 did not provide our office with these essential tools that many of our counterparts in other jurisdictions have.

The privacy laws of Quebec and Alberta, and those of several foreign jurisdictions, including common law countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia and Ireland, each have some or all such provisions to ensure organizations are held accountable for the way they use their increased flexibility to collect, use and disclose the personal information of consumers.

Issue 4: The need for common, or at least similar, principles for the public and private sectors

A fundamental aspect of the environment within which our privacy laws must be defined is the increased role of public-private partnerships and contracting relationships.

We have seen how public-private partnerships and contracting relationships involving digital technologies can create additional complexities and risks for privacy.

The pandemic certainly underscores this. Videoconferencing services and online platforms are allowing us to socialize, work, go to school and even see a doctor remotely but they also raise new privacy risks. Telemedicine creates risks to doctor-patient confidentiality when virtual platforms involve commercial enterprises. Meanwhile, e-learning platforms can capture sensitive information about students’ learning disabilities and other behavioural issues.

Our investigations into Clearview AI and the RCMP discussed elsewhere in this report are further examples of the risks involved in public-private partnerships.

Common privacy principles enshrined in both our public and private sector privacy laws would help address gaps in accountability where the sectors interact.

Issue 5: The need for interoperable laws, internationally and domestically

An important impetus for the Consumer Privacy Protection Act was the desire to maintain Canada’s European Union adequacy status. It is vital for the data that supports trade to travel outside our borders, without infringing upon the rights and values that we broadly share with our partners.

Interoperability between laws helps to facilitate and regulate these exchanges and it reassures citizens that their personal information is subject to similar protections when it leaves Canada. It also benefits organizations by reducing compliance costs and increasing competitiveness.

In August 2021, the OPC updated several guidance documents to reaffirm some of the types of personal information generally considered sensitive in the context of PIPEDA as a means of addressing European concerns about adequacy. The update sets out that certain types of information will generally be considered sensitive and require a higher degree of protection. This includes health and financial data, ethnic and racial origins, political opinions, genetic and biometric data, an individual’s sex life or sexual orientation, and religious/philosophical beliefs. Other jurisdictions have defined specific categories of personal information in their laws, including the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The updated guidance aims to better explain the concept of sensitive information under PIPEDA so it can be evaluated more accurately against the GDPR.

Interoperability is also an important domestic factor. Currently, with Bill C-11 now defunct and a number of proposals being put forward at the provincial level, there is the potential for a patchwork of privacy laws across Canada.

Quebec’s Bill 64, adopted into law in September 2021, and Ontario’s recent white paper on privacy law reform issued in June, both set out a rights-based approach to privacy as well as expansion of the scope of their laws. For instance, in the case of Quebec, it has expanded the scope of its law to include political parties which our office has also advocated for. Both also include more efficient adjudication and financial penalty regimes.

A jurisdictional comparative chart submitted to Parliament along with the OPC’s proposed amendments to Bill C-11 underscored how the Consumer Privacy Protection Act was frequently misaligned and actually less protective than the laws of other jurisdictions in Canada, Europe and elsewhere. Canada aspires to be a global leader in privacy and it has a rich tradition of mediating differences on the world stage. Adopting a rights-based approach, while maintaining the principles-based and not overly prescriptive approach of our private sector privacy law, would situate Canada as a leader showing the way in defining privacy laws that reflect various approaches and are interoperable.

Issue 6: The need for quick and effective remedies and the role of our office

Adopting adequate privacy legislation is not sufficient in itself. Laws must be enforced through quick and effective mechanisms. In many countries, this is done through granting the regulatory authority the power to issue orders and impose significant monetary penalties.

Such legislation does not seek to punish offenders or prevent them from innovating. It seeks to ensure greater compliance, an essential condition of trust and respect for rights.

It must be said that many businesses and organizations take their privacy obligations seriously. However, not all of them do. It is important that legislation not benefit the offenders.

Penalties must be proportional to the financial gains that businesses can make by disregarding privacy. Otherwise, organizations will not change their practices; minimal penalties would represent a cost of doing business they are willing to accept in order to generate profits. The proportional nature of penalties is also an advantage for smaller enterprises.

Unfortunately, the penalty provisions in Bill C-11 were largely hollow. First, the bill listed only a few violations as being subject to administrative penalties. The list did not include obligations related to the form or validity of consent, nor the numerous exceptions to consent, which are at the core of protecting personal information.

It also didn’t include violations to the principle of accountability, which, as noted, is required as an important counterbalance to the increased flexibility given to organizations in the processing of data.

Moreover, Bill C-11 proposed an additional layer of decision-making in the form of the Personal Information and Data Protection Tribunal that would have been responsible for imposing monetary penalties and hearing appeals against decisions of the OPC.

Such a tribunal does not exist in this form anywhere else and, we believe, would create unnecessary delays for consumers. Worse, it would encourage companies to choose the route of appeal rather than find common ground with the OPC when we are about to issue an unfavourable decision. We believe that the addition of this tribunal would only delay access to justice for consumers. The courts are perfectly capable of reviewing the legality of OPC decisions.

This does not mean we do not welcome transparency and accountability. On the contrary, we would gladly consult stakeholders in developing rules of practice that would ensure fairness towards parties in proceedings that may lead to the imposition of orders and penalties.

Finally, Bill C-11 would have imposed on the OPC new responsibilities, including the obligation to review codes of practice and certification programs, and advise individual organizations on their privacy management programs upon request; the obligation to rule on complaints before consumers can exercise a private right of action; and the obligation to rule within strict time limits.

We welcome the opportunity to work with businesses to ensure their activities comply with the law. However, adding all of these non-discretionary responsibilities, without giving the OPC the authority to manage its workload, is problematic.

An effective regulator is one that prioritizes its activities based on risk. Like other regulators, we need the legal discretion to manage our caseload so that we can respond to the requests of organizations and complaints of consumers in the most effective and efficient way possible, while reserving a portion of our time for activities we initiate, based on our assessment of risks to Canadians. A future law must take that into consideration.

We are confident it is possible to bring substantial improvements to this bill within its existing structure and without having to start over from scratch. This would be the most efficient and expedient way forward and we are ready to work with the government to this end.

Further Reading

- Submission of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada on Bill C-11, the Digital Charter Implementation Act, 2020, May 11, 2021

Artificial intelligence consultation

As part of our legislative reform policy analysis work, our office also launched a public consultation to examine AI as it relates to the private sector. We received 86 submissions and held 2 in-person consultations. We received feedback from industry, academia, civil society and the legal community. Based on that feedback, we issued recommendations for regulating the technology in November 2020, some of which also factored into our broader recommendations on Bill C-11. Our approach to AI in the private sector also informed our Privacy Act reform recommendations issued in March.

AI has become a reality of the digital age, supporting many of the services individuals use in their daily lives. It offers the potential to help address some of today’s most pressing issues affecting both individuals and society as a whole. AI can improve efficiency in the public sector and industry, and allow for new methods and solutions in fields such as public health, medicine and sustainable development. It also stands to increase efficiency, productivity, and competitiveness – factors that are critical to economic recovery post-pandemic and long-term prosperity.

However, uses of AI that involve personal information can have serious consequences for privacy. AI models have the capability to analyze, infer and predict aspects of individuals’ behaviours and interests.

AI systems can use such insights to make automated decisions about people, including whether they get a job offer, qualify for a loan, pay a higher insurance premium, or are suspected of unlawful behaviour. Such decisions have a real impact on lives, and raise concerns about how they are reached, as well as issues of fairness, accuracy, bias and discrimination.

We concluded AI presents fundamental challenges to all of PIPEDA’s foundational privacy principles. More specifically, it highlights the shortcomings of the consent principle in both protecting individuals’ privacy and in allowing its benefits to be achieved.

Our key recommendations included:

- Amending PIPEDA to allow personal information to be used for new purposes towards responsible AI innovation and for societal benefits;

- Creating the right to meaningful explanation for automated decisions and the right to contest those decisions to ensure they are made fairly and accurately; and

- Requiring organizations to design AI systems from their conception in a way that protects privacy and human rights.

With respect to AI, Bill C-11 included an approach that allowed for flexibility in the use of de-identified information for research and development purposes, while keeping such information within the confines of privacy law. Given the persistent risk of re-identification of de-identified information, we welcomed this approach.

However, significant improvements were needed to other aspects of Bill C-11 that concern AI in order to adequately protect people’s privacy rights. While Bill C-11 included transparency provisions related to AI, it only required that an explanation be provided of how personal information was obtained, instead of how it was used by an AI system to arrive at a decision. There were also no obligations in Bill C-11 for algorithmic traceability to support such explanations, or that would allow individuals to contest such decisions or request a human review of them. Clarity regarding the role of inferential data in categorizing and profiling individuals was also absent.

The risks of AI systems in undermining human dignity, self-determination, and fairness further demonstrate why a rights-based approach to privacy law is needed. Without it, AI can not only have severe consequences for individuals but also broader society, such as heightening inequality, discrimination, and societal divisions.

Further Reading

- A Regulatory Framework for AI: Recommendations for PIPEDA Reform, November 2020

- Policy Proposals for PIPEDA Reform to Address Artificial Intelligence Report, November 2020

- Global Privacy Assembly resolution on accountability in the development and use of artificial intelligence, October 2020

Privacy and federal political parties

An important matter the federal privacy laws do not address is the application of privacy law to political parties. Bill C-11 made no progress in this regard.

Furthermore, in May 2021, our office closed the file on a complaint related to alleged violations of PIPEDA by the New Democratic Party of Canada, the Liberal Party of Canada and the Conservative Party of Canada regarding alleged violations of PIPEDA in its current form.

The complainant alleged the parties were contravening PIPEDA by not properly informing Canadians on how they collected, used and/or disclosed their personal information to conduct political advertising, including “micro-targeted” advertising based on detailed profiles of individuals.

The complainant also claimed that activities undertaken by the parties were commercial activities and were therefore subject to the Act.

After reviewing the extensive representations and evidence submitted, our office concluded that the activities of the 3 federal political parties at issue in the complaint were not commercial in character within the meaning of the current Act.

We strongly believe that privacy laws should govern political parties, as is the case in some provinces and as we recommended in our Bill C-11 submission. However, we are required to apply the law as it stands today and that is why we have dismissed the complaint against certain federal parties.

Further Reading

- Letter regarding complaint against federal political parties, March 25, 2021

- Guidance for federal political parties on protecting personal information, April 1, 2019

Privacy Act reform

Turning now to regulation and reform over public sector privacy matters, the government’s Privacy Act reform consultation document did a considerably better job overall of addressing many similar concerns to those we raised in the context of Bill C-11.

It proposed substantive changes that represented significant strides toward a law that is in step with modern data protection norms.

Unlike Bill C-11, it included a proposed purpose clause that specifies that a key objective of the law is “protecting individuals’ human dignity, personal autonomy, and self-determination,” thereby recognizing the broad scope of privacy as a human right.

The government also proposed measures aimed at providing meaningful oversight and quick and effective remedies, such as order-making powers for our office and expanded rights of recourse to Federal Court.

As noted in our submission to the government’s consultation, one of the more fundamental changes proposed is the inclusion of foundational and broadly recognized data protection principles – including a new “identifying purposes” principle, in addition to a “limiting collection” principle to restrict the types and amount of personal information federal public bodies may collect. As well, under the proposed collection threshold, a federal public body would be limited to collecting only the personal information “reasonably required” to achieve a purpose relating to its functions and activities, or where it is otherwise expressly authorized by another act of Parliament.

We noted that the shift towards digitization has made collection, use, disclosure and retention of information much easier for government and that imposing a stricter threshold for collection would limit potential over-collection by federal government institutions.

Our investigation into Statistics Canada’s collection of Canadians’ personal information from a credit bureau and planned collection from financial institutions underscored the importance of limiting the collection of personal information to what is necessary and is proportional in the circumstances. So too has much of our pandemic-related work, including that involving the COVID Alert exposure notification app and ongoing discussions on vaccine passports.

In fact, the assessment framework we released in April 2020 to assist government institutions faced with responding to the COVID-19 crisis echoed a number of the measures we’ve put forward in our legislative reform submissions. For instance, we recommended the collection of personal information by federal institutions be governed by the widely accepted necessity and proportionality standard, which is the norm in many modern laws internationally and in Canada, at the provincial level.

The Department of Justice has said its “reasonably required” collection standard, in practice, would be “essentially equivalent to leading international standards.”

If that’s the case, we welcome the proposal to raise the current threshold (relevance) and accept that a “reasonably required” standard may be workable if the aim is to add clarity to the law, while yielding results similar to the longstanding principles of necessity and proportionality.

To ensure alignment with modern standards, we recommended amendments to the proposed factors to be taken into account as part of the “reasonably required” assessment, including that the specific, explicit and lawful purposes be identified, and personal information collection be limited to what is reasonably required in relation to those purposes, as well as whether the loss of privacy or other fundamental rights and interests of the individual is proportionate to the public interests at play.

The consultation document also included proposals to address concerns regarding AI, including alignment with federal policy instruments to ensure that individuals are aware when they are interacting with these systems, that they understand what types and sources of personal information these systems use, and that they generally know how they function. While these are good objectives for increasing transparency, it’s important to provide individuals with actionable rights, given that the use of automated decision-making based on personal information can be the determinant of whether an individual receives government services, benefits, or is eligible for various programs.

Consistent with our recommendations regarding Bill C-11, our submission to the Department of Justice made in March reflected our belief that individuals should be provided with a right to a meaningful explanation of automated decisions (including a standard for the level of specificity such explanations contain), and a right to contest such decisions. These are important in ensuring that the traditional data protection principles of accuracy and accountability can continue to adequately protect privacy in the context of AI, which fundamentally challenges such privacy principles. They are also particularly important in the public sector context to respect natural justice and procedural fairness.

We look forward to continued collaboration with the Department of Justice on this important initiative for Canadians to ensure strong protections for their privacy rights.

Further Reading

- OPC submission to the Department of Justice Public Consultation on the Modernization of the Privacy Act, March 22, 2021

Review of the Access to Information Act

The Access to Information Act (ATIA) and the Privacy Act both play a central role in preserving our information rights as our society becomes increasingly digital. Both laws are essential to fostering a more open, transparent government and upholding the tenets of democracy.

Our federal access to information regime can ensure that Canadians have open, accessible and trustworthy information from government. Where personal information is at stake, Canada’s privacy laws limit the circumstances under which that information can be disclosed.

In February 2021, our office participated in the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s statutory review of the ATIA. This review presented an opportunity to examine issues that lie at the intersection of both the ATIA and the Privacy Act.

Our submission expressed support for the modernization of Canada’s access laws to facilitate greater openness and transparency, but not at the expense of privacy.

We noted modern access and privacy laws are needed if we are to draw value from data while preserving our democratic values and the protection of our rights in a digital environment.

Given the high degree of intersection between the ATIA and the Privacy Act – particularly with respect to concepts such as de-identification, publicly available information, and the definition of personal information – we strongly recommended amendments to the laws be made concurrently. This is fundamental to both Acts continuing to being read as a seamless code of information rights. To that end, the OPC and the Office of the Information Commissioner of Canada (OIC) have implemented a Memorandum of Understanding to help identify and guide instances where the OIC may consult with the OPC on intersecting issues.

Further consideration should be given to how competing privacy and information interests should be balanced in the context of public interest disclosures.

We note that the Department of Justice has indicated that it will factor in the comments received during the review of the ATIA when it undertakes its review of the Privacy Act. We hope these reviews will present an opportunity for both ministers to address the interplay between the ATIA and the Privacy Act through concurrent amendments.

Further Reading

- Submission on the statutory review of the Access to Information Act, February 17, 2021

Other legislative initiatives in Canada

Over the last year, we have seen a number of provincial jurisdictions take steps in the right direction to enhance their privacy laws to better protect Canadians.

In Quebec, the provincial government, through the passage of Bill 64, has granted citizens clear, enforceable rights such as the right to erasure. Under provisions that will come into force in 2 years, the enforcement powers of the Commission d’accès à l’information (CAI) will also be significantly increased.

In September 2020, Commissioner Therrien appeared before the Committee on Institutions of the National Assembly of Quebec while the bill was being considered. He noted that a number of elements were consistent with the law reform proposals our office has put forward.

For example, it includes provisions that address profiling and protecting the right to reputation, which are consistent with our approach to rights-based legislation. It subjects political parties to the private sector law, and has a more efficient adjudication and financial penalty regime.

Our office also participated in the public consultation conducted by the Special Committee to Review the Personal Information Protection Act of British Columbia.

Our submission included several points made in our Bill C-11 submission to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics and supported recommendations put forth by British Columbia Information and Privacy Commissioner Michael McEvoy. This included the fundamental benefits of a mandatory breach reporting regime, the need for modern enforcement mechanisms to include both order-making as well as the ability to issue fines, and how coordination at the domestic and international level is required to effectively protect privacy in today’s digital economy.

Finally, in June 2021, the Government of Ontario released a white paper seeking input from privacy stakeholders and Ontarians on elements of a modern privacy law for Ontario’s private sector. Among the highlights, the white paper proposes that, consistent with the recommendations of the OPC’s Bill C-11 submission, Ontario could establish a fundamental right to privacy as the underpinning principle for its new privacy law, ensuring that Ontarians are protected.

The proposal also includes more effective remedies than those found in Bill C-11, specifically, IPC-issued penalties rather than the tribunal model provided for in Bill C-11. In September 2021, the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario released its response to the white paper urging the Ontario government to move forward with its plans despite the uncertainty of law reform at the federal level.

Further Reading

- Appearance before the Committee on Institutions of the National Assembly of Quebec regarding Bill 64, An Act to modernize legislative provisions as regards the protection of personal information, September 24, 2020

- Questions and answers – Bill 64, September 24, 2020

- Statement before the Special Committee to review BC’s Personal Information Protection Act, June 22, 2021

Conclusion

In Canada, we are now in the midst of a fourth industrial revolution. Digital technologies are being adopted at a staggering pace, from our largest cities to our most remote northern communities. New technologies can plainly provide important economic and social benefits, but they also present huge challenges to legal and societal norms that protect fundamental Canadian values.

Privacy is a fundamental right, recognized as such by Canada as a signatory to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which was proclaimed in 1948. It is nothing less than a prerequisite for the freedom to live and develop independently as persons away from the watchful eye of a surveillance state or commercial enterprise, while still participating voluntarily and actively in the regular, and increasingly digital, day-to-day activities of a modern, democratic society.

Only through respect for the rights and values we cherish will Canadians be able to safely enjoy the benefits of these technologies. Unfortunately, bad actors have eroded our trust and without law reform, trust will continue to erode.

Lawmakers have an opportunity to restore and build confidence in our digital economy. We can do this by integrating core Canadian values such as respect for human rights into our laws.

Our office is committed to working with the government and with Parliament to develop laws that will effectively protect the privacy rights of Canadians in a rapidly evolving digital environment.

Privacy by the numbers

| Privacy Act complaints accepted | 827 |

|---|---|

| PIPEDA complaints accepted | 309 |

| Data breach reports received under PIPEDA | 782 |

| PIPEDA complaints closed through early resolution | 210 |

| Privacy Act complaints closed through early resolution | 441 |

| Advisory engagements with private-sector organizations | 13 |

| Privacy Act complaints closed through standard investigation | 414 |

| Well-founded complaints under the Privacy Act | 64% |

| PIPEDA complaints closed through standard investigation | 86 |

| Well-founded complaints under PIPEDA | 73% |

| Bills, legislation and parliamentary studies reviewed for privacy implication |

17 |

| Data breach reports received under the Privacy Act | 280 |

| Advice provided to public-sector organizations following PIA review or consultation |

136 |

| News releases and announcements | 54 |

| Privacy impact assessments (PIAs) received | 81 |

| Public interest disclosures by federal organizations | 491 |

| Information requests | 7,090 |

| Tweets sent | 443 |

| Advisory consultations with government departments | 109 |

| Parliamentary committee appearances on private- and public-sector matters |

3 |

| Speeches and presentations | 32 |

| Twitter followers | 18,616 |

| Visits to website | 2,491,736 |

| Blog visits | 26,754 |

| Publications distributed | 1,260 |

The Privacy Act: A year in review

Our office’s public sector work in the past year continued to have a strong focus on privacy issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Collaborating with many partners within Canada and abroad, we contributed significant efforts to help ensure privacy principles would be considered and applied, in tandem with efforts to support public health goals, for example in relation to contact tracing technologies, vaccine passports, border issues, the role of telecommunications companies and the workplace. We experienced a significant increase in requests for advice and engagements, in terms of more privacy impact assessments and consultations with our office on a variety of key issues, including in the area of public safety and national security, but we saw fewer public sector breaches reported to us, despite concerns that breaches continue to take place. We exceeded our backlog reduction goals and improved complaint processes to create greater efficiencies, for example in improving front-end information gathering to support our investigations and in employing various strategies such as early resolution.

The following section highlights key initiatives under the Privacy Act in 2020-21.

Spotlight on pandemic-related work

From the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, our office’s approach has focused on how personal information can, and should, remain protected using a flexible and contextual approach during a grave national health emergency. Privacy is not an impediment to public health, and in 2020 we demonstrated measures to protect privacy and build public trust in government public health initiatives. Throughout the pandemic, Canadians have shown they continue to care about the protection of their personal information in this context, and we now know that public health and privacy can go hand in hand.

The pandemic has resulted in a wide range of federal government initiatives with a potential impact on privacy.

The federal government has engaged with our office on a range of files, including numerous initiatives related to COVID-19 infection tracking and tracing, border controls and initiatives to provide benefits during the economic crisis. This work included ongoing engagement on the government’s COVID-19 exposure notification application.

In general, the government has consulted with our office on key COVID-19 initiatives such as COVID Alert, benefit programs and, more recently, proof of vaccine credentials. As always, we recommend that we be consulted as soon as possible on initiatives that may impact the privacy of Canadians and that assessments of any privacy impacts be conducted ahead of implementation.

Health Canada – COVID Alert app

We have continued to provide advice to Health Canada on the national COVID-19 exposure notification application COVID Alert, as it evolved and new features were added.

Our initial review of the app’s privacy risks and measures in place to mitigate such risks was informed by the joint statement issued in May 2020 by federal, provincial and territorial privacy commissioners, entitled Supporting public health, building public trust: Privacy principles for contact tracing and similar apps. This is discussed in detail later in this report.

As noted in our 2019-2020 Annual Report, we supported the app on the condition that it would be voluntary, and as long as its use was found to be effective in reducing transmission of the virus.

During the course of our consultations with Health Canada, we made a number of recommendations that were implemented. We have advised the Government of Canada to closely monitor the app and that it be decommissioned if shown not to be effective.

At the time of writing, Health Canada was leading an evaluation of the app. Our office was participating with Health Canada on that evaluation. The app’s design and implementation were being assessed for necessity and proportionality, including effectiveness, and compliance with the principles outlined in the statement made with our provincial and territorial colleagues. From our perspective, a strong demonstration of effectiveness of the app will be a key focus of the evaluation. It is expected that the evaluation will be completed in the fourth quarter of 2021.

Further Reading

- Supporting public health, building public trust: Privacy principles for contact tracing and similar apps, May 7, 2020

- Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada Review of the COVID Alert app, July 31, 2021

- Letter to shadow ministers, August 20, 2020

- Letter to committee members, August 27, 2020

Public Health Agency of Canada – Vaccine passports

As the pandemic response evolved, governments in Canada and around the world turned their attention to the idea of a credential or certificate confirming vaccination status, sometimes called “vaccination passports.” Discussions are centering on the creation and use of this tool to enable economic recovery and more normal business practices to proceed in a secure manner.

Our office has been evaluating the viability of a vaccine passport and/or certificate in the Canadian context, especially concerning the necessity and effectiveness of this measure in enabling secure activities, and proportionality between the purpose for and collection of sensitive health information.

In May 2021, we issued a joint statement with our provincial and territorial counterparts that outlines fundamental privacy principles that should be adhered to in the development of vaccine passports. More detailed information can be found in the “domestic cooperation” section of this report.

At the time of writing this report, we were in discussions with the Government of Canada and our provincial and territorial counterparts on this initiative.

Further Reading

- Privacy and COVID-19 Vaccine Passports: Joint Statement by Federal, Provincial and Territorial Privacy Commissioners, May 19, 2021

Public Health Agency of Canada – Canadian border enhancements in response to COVID-19

At the beginning of 2020, the Government of Canada announced new rules on international travel in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) is the lead institution for ensuring quarantine requirements are respected, and for ensuring compliance checks with travellers are completed post-arrival.

Our office consulted regularly with PHAC and its partner enforcement institutions as new measures under the Quarantine Act related to COVID-19 were implemented at Canadian borders.

This included an early consultation with the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) about the paper coronavirus form issued to travellers arriving in Canada from the Hubei province of China. After this initial consultation, measures evolved and expanded quickly. Our office provided advice and recommendations on multiple phases of PHAC’s ArriveCAN mobile device application and web browser platform, which enables international travellers to report on their compliance with mandatory isolation measures. Travellers can use the ArriveCAN app to provide the government with prescribed travel information when entering Canada and during their required isolation period.