Annual Report to Parliament 2010 on the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act

This page has been archived on the Web

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

112 Kent Street

Ottawa, Ontario

K1A 1H3

(613) 947-1698, 1-800-282-1376

Fax (613) 947-6850

TDD (613) 992-9190

© Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada 2011

Cat. No. IP51-1/2010

ISBN 978-1-100-52921-9

June 2011

The Honourable Noël A. Kinsella, Senator

The Speaker

The Senate of Canada

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A4

Dear Mr. Speaker:

I have the honour to submit to Parliament the Annual Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada on the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act for the period from January 1 to December 31, 2010.

Sincerely,

(Original signed by)

Jennifer Stoddart

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

June 2011

The Honourable Andrew Scheer, M.P.

The Speaker

The House of Commons

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A6

Dear Mr. Speaker:

I have the honour to submit to Parliament the Annual Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada on the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act for the period from January 1 to December 31, 2010.

Sincerely,

(Original signed by)

Jennifer Stoddart

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

The Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act, or PIPEDA, sets out ground rules for the management of personal information in the private sector.

The legislation balances an individual's right to the privacy of personal information with the need of organizations to collect, use or disclose personal information for legitimate business purposes.

PIPEDA applies to organizations engaged in commercial activities across the country, except in provinces that have substantially similar private sector privacy laws. Quebec, Alberta and British Columbia each have their own law covering the private sector. Even in these provinces, PIPEDA continues to apply to the federally regulated private sector and to personal information in inter-provincial and international transactions.

PIPEDA also protects employee information, but only in the federally regulated sector.

Commissioner’s Message

Protecting privacy rights is an increasingly complex challenge in the digital age, when more and more of daily life plays out on the Internet and our activities can so easily be tracked, stored, shared and analyzed.

The complex privacy issues of the online world were a major focus of our work in 2010.

As our social world shifts online, privacy safeguards have become critical. We were pleased to report in September that we were satisfied with how Facebook had implemented privacy improvements in response to our comprehensive investigation of the site.

Our investigation of Google’s collection of sensitive personal data transmitted over unsecured wireless networks, meanwhile, showed the deficiencies in governance controls on privacy.

In the context of this complex, rapidly evolving environment, we heard questions being raised about whether privacy is evaporating in our current era of digital exhibitionism.

Of course, concepts of privacy do evolve over time and from generation to generation. However, it is clear to me that privacy continues to be a deeply cherished value – and we saw plenty of evidence of this in 2010.

“New Social Norm”

Early in the year, Mark Zuckerberg, the chief executive officer of Facebook, offered his view of privacy. He said:

People have really gotten comfortable, not only sharing more information and different kinds, but more openly and with more people. That social norm is just something that has evolved over time. We view it as our role … to constantly be innovating and be updating what our system is, to reflect what the current social norms are.

I don’t disagree with the observation that social norms are changing. Privacy looks different today than it did a generation – or even a decade – ago. It is startling how people post the nitty-gritty of their intimate lives online.

But I also take heart in all the signs that people – including the biggest Internet users, youth – do, in fact, still care very much about privacy.

We see evidence of this whenever we go out to schools to talk with children and teens from Grades 4 to 12 about managing their online reputations. At the end of each presentation, young people ask questions that show how interested they are in privacy. They want to know how to manage who sees what in their online profiles. They want to know how they can see everything that others are posting about them. And they often ask how to permanently delete things – everything from items they wish they hadn't posted to old quiz information that they don't want on the Internet anymore.

Privacy remains an incredibly important and cherished value to Canadians – and to people around the world.

Those trying to convince us that privacy is out of fashion are consistently the people who stand to profit from its demise.

Personal information has become a valuable commodity. Companies make money from the use of personal information – it’s no wonder that some would like us to believe that privacy doesn’t matter.

I’ve even heard the question asked: “Can we have both privacy and innovation?”

The answer is a resounding Yes. Privacy does not stand in the way of innovation.

The pressure on privacy is not just the result of new social standards or new and captivating technologies. In the commercial sphere where PIPEDA applies, it chiefly comes from the fact that there is big money to be made in pushing the privacy boundaries.

Push Back

But people are pushing back.

We’ve seen that with the two giants of the online world – Facebook and Google.

Facebook users spoke up – loudly – after the social networking site rolled out a series of changes that made it far more difficult for users to protect their privacy. The outcry had an impact and Facebook scrambled to ratchet back some of its privacy modifications in order to quell the criticism.

Google, meanwhile, was also the target of a privacy backlash when it launched Google Buzz early in 2010.

The company took Gmail, which had been a private, web-based e-mail service, and abruptly melded it with a new social networking service. Google automatically assigned users a network of “followers” from among people with whom they corresponded most often on Gmail, without adequately informing those users about how this new service would work or providing sufficient information to permit informed consent.

There was a storm of protest by users around the world who were understandably concerned that their personal information was being disclosed.

The rollout of a product with such significant privacy flaws betrayed a disappointing disregard for fundamental privacy norms and laws. I was among a group of 10 international data protection authorities who jointly wrote to Google to remind it of the need to respect the laws of the countries in which they launch their products. That initiative was another sign of the continuing commitment to privacy protection right around the globe.

To its credit, Google quickly apologized to its users and introduced changes to address the widespread criticism.

Privacy Still Matters

These two stories illustrate the fact that people do care.

Yes, many people – particularly young people – are willing to share more than we did in the past. But they want to do so on their own terms. They want to be able to control their personal information – and that just happens to be one of the basics of privacy law in Canada and many other countries.

Canadians clearly like many of the new services being offered online and they want to continue using them in order to connect with one another. More than half of Canadians are now on Facebook.

It’s also clear, however, that people want a service that respects their privacy. This is what Canadians have told my Office in letters and telephone calls – and it is what I hear in my travels across the country.

I have a very strong sense that we are speaking on behalf of Canadians when we ask these big online companies to respect our laws.

Privacy Online

Online privacy issues are an area of increasing focus for my Office, which is why we’ve chosen to make it a major theme in this year’s annual report.

It’s certainly an area full of challenges. The issues are often complex and highly technical. Websites seem to change every day, so a great deal of effort is required to keep up with what’s happening. The online world that Canadians access for products and services is global – we’re often dealing with organizations based outside the country.

There’s no doubt that the digital world is raising monumental challenges for privacy rights. That means we need to work harder and smarter, not throw in the towel on privacy and “get over it” – as one tech titan famously stated a number of years ago.

There is a lot we can do in the face of new privacy risks stemming from technological change:

- We need to enforce our privacy laws and ensure they remain modern and relevant.

- We need even more cooperation between privacy authorities – we’re far stronger when we speak with one voice.

- We, as a society, must ensure that our privacy literacy matches our online literacy because, at the moment, there’s a gap.

Modern Legislation

Technologies are developing at an astonishing rate and these changes are raising interesting new questions and challenges from a legal perspective.

Are laws designed for a bricks and mortar world up to the task of protecting privacy in the online context? Do we need new laws? How do you deal with jurisdictional questions and enforcement when dealing with global online companies?

It is clear that our current regulatory framework for protecting the privacy rights of Canadians is being tested in the face of rapidly changing technologies.

It is critical that we ensure that we are constantly updating our laws to meet current and future challenges.

The architects of the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) had the foresight to make the legislation technology neutral and also include a requirement for a Parliamentary review of the Act every five years.

The first review began in late 2006 and the next one is expected to start in 2011.

My Office has already begun laying some of the groundwork for the upcoming review.

We have commissioned a report on the effectiveness of our current ombuds model. As well, we held public consultations on the privacy issues related to both the online tracking, profiling and targeting of consumers by marketers and other businesses as well as cloud computing practices.

Both the report and our public consultations will help shape my Office’s input during the next PIPEDA review.

The report was prepared by two noted legal scholars, Dean of Osgoode Hall Law School Lorne Sossin and Professor France Houle of the Université de Montréal. We asked them to examine the effectiveness of the ombuds model in protecting personal information in the private sector, particularly in light of changes in the technological, economic and legal context since PIPEDA was first enacted.

In their analysis, these authors suggest that the current ombuds model has had mixed success.

On the positive side, the authors take the view that my Office has succeeded in accomplishing important goals related to compliance by working with large industry sectors such as banking and insurance, building trust across the private sector, providing guidance on the interpretation and application of PIPEDA, responding to complaints, inquiries and concerns, raising awareness of PIPEDA and generally enhancing the profile of privacy issues.

However, they are also of the view that the ombuds model may be less effective in promoting compliance where small- and medium-sized businesses are concerned.

The professors have suggested, as an option going forward, that my Office could acquire targeted and limited power to make orders, including the ability to impose penalties such as fines. They also propose explicit guideline-making power, to assist with the fair and transparent implementation of new order-making powers.

My Office is assessing the authors’ analysis, mapping it onto our experience under PIPEDA to date, and comparing it with our own views of the merits and effectiveness of the ombuds model. The authors’ analysis will undoubtedly make a significant contribution to the public discourse on future evolutions of PIPEDA.

With our public consultations, meanwhile, we developed a deeper understanding of a couple of emerging technological trends that will have a significant impact on the privacy of Canadians.

The consultations were an historic first for us. We invited written comments, but also held a series of day-long panel discussions in Toronto, Montreal and Calgary, canvassing a broad range of views from business, government, academics, consumer associations and civil society.

As this annual report was being prepared, we were completing a final report on the consultations for publication in 2011.

As we begin thinking about recommendations for PIPEDA reform during the upcoming Parliamentary review, we are also looking forward to changes resulting from the last review.

The print version of the 2010-2011 Annual Report to Parliament contained an error regarding the dates of the two bills mentioned in the following paragraph.

They are contained in two bills – one that received Royal Assent in December 2010 and another that was before Parliament at the beginning of 2011.

The legislation that was still under consideration by Parliament would, among other things, amend PIPEDA to require organizations to notify my Office and affected individuals following significant data breaches. That would be a welcome change.

The bill that has passed is aimed at curbing the amount of damaging and deceptive electronic communications (spam messages) that circulate in Canada. In the year ahead, we look forward to taking on our enforcement responsibilities under this new anti-spam law.

This legislation amends PIPEDA to provide my Office greater discretion to refuse or discontinue complaints and to permit us to share information with our domestic and international counterparts. These two new discretionary powers apply to investigations generally, whether the matter involves spam or other privacy issues.

Increased Cooperation

We must also work beyond our borders. Canada on its own cannot possibly tackle the plethora of privacy concerns cropping up across the World Wide Web.

There has also been a lot happening on the global stage. For example, we are taking part in a number of initiatives to develop an international privacy standard and we’re a founding member of the new Global Privacy Enforcement Network.

We have also been involved in the privacy work of Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which in 2010 marked the 30th anniversary of its groundbreaking Guidelines on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data.

On a more informal level, in 2010 we saw an unprecedented collaboration of 10 data protection offices coming together to send a strong message to Google and other online companies about the need to respect privacy laws around the world when launching new products and services.

All of the authorities involved in that project recognized the need to – as much as possible – join forces to ensure our messages are heard.

Privacy Literacy

Another key to online privacy is to find ways to build a better understanding of privacy issues on the part of both consumers and organizations.

Canada is a nation of early adopters when it comes to new technologies, with 80 percent of Canadians over the age of 16 now online. And while we are sophisticated when it comes to online literacy, I think our privacy literacy in the context of the digital world could be improved.

Many people don’t know they’re leaving a trail of digital bread crumbs when they click their way through websites and from website to website. They don’t know that those crumbs are stored, analyzed and accessible. And they don’t understand that this information may be used in ways they never imagined.

How many people actually read privacy policies? How knowledgeable are people about securing their home computers and networks?

The need for improved privacy literacy applies not only to individuals, but also to organizations. Businesses need to ensure that their employees are privacy literate; that they have knowledge of how personal information should be used and handled in the context of privacy values.

We’re strong advocates for this kind of training, which can save an organization a lot of grief – and money. An employee who has spent time thinking and learning about privacy is far less likely to leave a laptop containing personal information on the front seat of her car or to be cavalier about punching in a fax number when sending sensitive records.

Training – ongoing training – makes people stop and think about the need to protect personal information. It builds awareness that personal information should be private by default.

A recent poll conducted for my Office found that only 37 percent of businesses had provided privacy training for employees. We need to do better.

Toronto Office

The year 2010 marked a very exciting development in the history of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada: We opened our first office outside of the nation’s capital.

Our new Toronto office creates an opportunity for a stronger presence for outreach and PIPEDA investigation work. A very large percentage of our complaints against private-sector organizations involve companies located in the Greater Toronto Area.

We expect that the Toronto office is going to lead to stronger, more effective relationships with our stakeholders there – and that’s ultimately going to mean better privacy protection for Canadians.

A New Mandate

At the end of 2010, I was honoured to be reappointed as Privacy Commissioner of Canada.

It has been a great privilege to serve Canadians and Parliament for the past seven years and I deeply appreciate that the Prime Minister and Parliament have confidence in me to continue on in this role. I look forward to the opportunity to build on what my Office has already accomplished.

I have been touched and gratified by the accolades that my Office has received for its work in recent years. While there are still improvements I would like to make to ensure that we are delivering the best possible service to Canadians, we have many achievements to be proud of.

The secret to these successes is the dedicated team of professionals at the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada. They are a thoughtful, creative, passionate, determined and tireless group that is always ready to meet the challenge of increasingly complex privacy issues.

Our Office has grown in recent years and we’ve been lucky to have some exceptionally talented and highly knowledgeable people join us.

This annual report is an opportunity to offer everyone in the Office my profound appreciation for all their outstanding work, which has a very positive impact on the day-to-day lives of people across the country.

In mid-2010, our Assistant Commissioner for PIPEDA, Elizabeth Denham, was appointed Information and Privacy Commissioner for British Columbia. While we miss her both on a professional and personal level in Ottawa, we are delighted that we now have another strong partner in British Columbia and the opportunity to continue working together on issues of mutual interest.

As a result of that appointment, Assistant Commissioner Chantal Bernier’s responsibilities have been expanded and she is now responsible for both the Privacy Act – Canada’s federal public sector privacy legislation – and PIPEDA. I am grateful to her for taking on such an enormous challenge and would like to publicly express my deep gratitude for her unfailing commitment and exceptional leadership in the Office.

There will be many new and ongoing privacy issues for our team to tackle together over the next three years. We still have many challenges before us, most notably, improving service to Canadians who reach out to our Office for help.

Protecting privacy in this rapidly transforming landscape demands agile and creative responses. This is what we will continue to strive to deliver on behalf of all Canadians.

Jennifer Stoddart

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

Privacy by the Numbers

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada in 2010

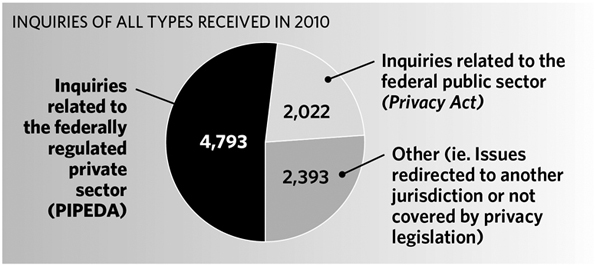

| PIPEDA inquiries received | 4,793 |

|---|---|

| PIPEDA early resolution complaints received | 108 |

| PIPEDA complaints received | 99 |

| PIPEDA investigations closed | 249 |

| Draft bills and legislation raising PIPEDA issues reviewed for privacy implications | 13 |

| Private-sector policies or initiatives reviewed (For example, a written analysis of a new technological application, or a paper on an industry practice to keep staff up to date on new developments.) |

30 |

| Policy guidance documents issued | 14 |

| Research papers issued | 5 |

| Parliamentary committee appearances | 13 |

| Other interactions with Parliamentarians or staff (For example, meeting with MPs or Senators.) |

40 |

| Speeches and presentations delivered | 150 |

| Contribution agreements signed | 16 |

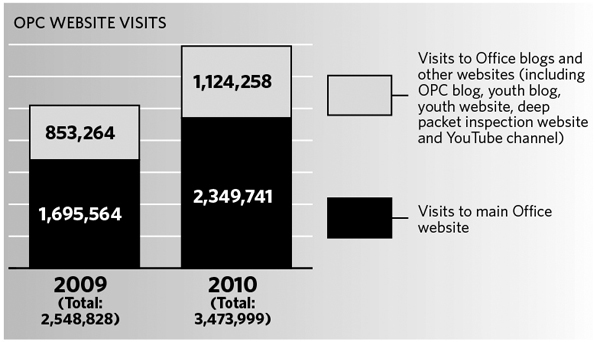

| Visits to main Office website Visits to Office blogs and other websites (including OPC blog, youth blog, youth website, deep packet inspection website and YouTube channel) |

2,349,741 1,124,258 |

| Total | 3,473,999 |

| “Tweets” sent | 700 |

| Publications distributed | 15,478 |

| Media interviews | 250 |

| News releases | 42 |

Note: Unless otherwise specified, these statistics also include activities under the Privacy Act, which are described in a separate annual report.

Chapter 1

The Privacy Landscape

Key Accomplishments in 2010

1.1 Serving Canadians

Public Inquiries

Canadians phoned or wrote to our Office more than 9,200 times during 2010. Approximately half of those calls and letters involved a matter related to privacy issues in the private sector covered by PIPEDA. Other inquiries related to the Privacy Act, which applies to the federal public sector, or involved another jurisdiction or issues not exclusive to either of the Acts we enforce.

On the PIPEDA side, we continued to see a growing number of inquiries related to online issues.

For more information, see section 4.1

Public Complaints

Largely as a result of our strengthened efforts to resolve issues more rapidly at the front end, the number of formal complaints registered with our Office dropped significantly.

We received 108 early resolution complaints and 99 formal investigation complaints related to the private sector, for a total of 207 complaints. That compares with 231 formal complaints received in 2009.

As described in section 4, we have been extremely successful in our efforts to help individuals and organizations try to resolve issues before they become formal complaints.

In particular, we have established a formal early resolution process, which has quickly become an important tool for addressing issues in a timely manner. In some cases, an issue that would have taken months to resolve through the official complaint investigation process is now concluded in a matter of days.

In most early resolution cases, we were able to reach a satisfactory resolution without opening a formal investigation.

Complaint Investigations

We closed 249 complaints relating to the private sector in 2010.

Online issues continued to play a major factor in our investigation work. In 2010, we worked on privacy issues related to major online players such as Facebook and Google. We also investigated the popular online dating site, eHarmony.

We’ve made online issues a special focus of this year’s annual report. Summaries of our complaint investigations involving the online world are included in section 2.

Information on our other complaints investigation work is provided in section 4.

Public Awareness

The Commissioner, Assistant Commissioners and other officials from our Office delivered 150 speeches and presentations, many of them on private-sector privacy issues, during the course of 2010.

We were also asked to provide comment for dozens of media stories – many of them related to privacy issues cropping up in the online world.

Our paper publications continue to be in high demand – we distributed 15,478 copies of our pamphlets, brochures and guides at conferences and upon request from organizations and individuals during the year.

Meanwhile, the number of visits to our website soared by 36 percent from the previous year.

We continue to put a special focus on online youth privacy, with websites designed for young people and a popular school presentations program. In 2010, we also supported the first annual PrivacyCampTO, a conference on digital privacy.

For more information on our public awareness initiatives, please see section 5.

1.2 Supporting Parliament

Appearances before MPs and Senators

During 2010, our Commissioner, Assistant Commissioners and other officials of the Office made 13 formal Parliamentary committee appearances.

In October, for example, we appeared before the House of Commons Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics concerning its study on the privacy implications of street-level imaging applications.

Google’s Street View imaging cars had collected payload data from unsecured wireless networks. We initiated our own investigation into this matter.

We were pleased that the Committee took such an interest in the personal information handling practices of Google and the protection of Canadians’ privacy. In our testimony, we continued to stress the importance of ensuring that privacy remains a key consideration as any organization develops new products and services involving the use of personal information.

In January 2011, the Committee issued its report, saying it was satisfied that the privacy concerns of Canadians with regard to street-level imaging technology are being taken seriously by all parties involved.

The Committee said it was reassured that our Office continues to monitor developments to ensure compliance with Canadian law. For its part, the Committee said it would also continue to monitor the issue and revisit the matter if necessary.

In its report, the Committee stated: “(T)echnology innovators need to ensure that privacy protection is a core consideration at the development stage of any new project. Potential privacy risks should be identified and eliminated or reduced at the onset of new projects and not be left to be addressed as costly afterthoughts.”

The issue of national security – sometimes in a context that involves the private sector –continued to be a subject of dialogue between our Office and parliamentary committees.

For example, in November, we appeared before the House of Commons Standing Committee on Transport, Infrastructure and Communities on Bill C-42, An Act to amend the Aeronautics Act. The bill – prompted by the requirements of the U.S. Secure Flight program – would allow the sharing of personal information between Canadian airlines and U.S. authorities when an aircraft flies over, but does not land in, the United States.

While we understand that U.S. sovereignty extends to its airspace, we felt it was important to express our concerns about the potential consequences of the U.S. Secure Flight program for the privacy of Canadian travellers.

In our testimony, we noted that the Canadian government has an important role to play in working with the U.S. government and Canadian airlines to minimize the impact of Secure Flight. We proposed that the government ensure that the minimum amount of personal information is disclosed, that it question retention periods, and also negotiate robust and accessible redress mechanisms.

We also made presentations at other committee hearings, including:

- Senate Standing Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology on Bill C-36, the Canada Consumer Product Safety Act - November 25, 2010.

- House of Commons Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics on the the 2009 Annual Report to Parliament on PIPEDA and the 2009-2010 Annual Report to Parliament on the Privacy Act - October 19, 2010.

- House of Commons Standing Committee on Transport, Infrastructure and Communities on aviation safety and security - May 11, 2010.

Over the course of the year, we also had many other more informal interactions with Parliamentarians, including follow-ups to committee appearances, subject-matter inquiries from Members of Parliament, teleconferences, face-to-face meetings and briefings.

Reviews of draft bills and legislation with potential privacy implications

Meanwhile, we examined a total of 27 bills introduced in Parliament in order to consider potential privacy implications. Roughly half of those involved issues related to the private sector.

These included the following bills:

- C-22 - An Act respecting the mandatory reporting of Internet child pornography by persons who provide an Internet service.

- C-28 - An Act to promote the efficiency and adaptability of the Canadian economy by regulating certain activities that discourage reliance on electronic means of carrying out commercial activities, and to amend the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission Act, the Competition Act, the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act and the Telecommunications Act.

- C-29 - An Act to amend the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act. (Safeguarding Canadians’ Personal Information Act.)

- C-32 - An Act to amend the Copyright Act. (Copyright Modernization Act.)

- C-36 - An Act respecting the safety of consumer products. (Canada Consumer Product Safety Act.)

- C-42 - An Act to amend the Aeronautics Act. (Strengthening Aviation Security Act.)

- C-50 - An Act to amend the Criminal Code. (Improving Access to Investigative Tools for Serious Crimes Act.)

- C-51 - An Act to amend the Criminal Code, the Competition Act and the Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Act. (Investigative Powers for the 21st Century Act.)

- C-52 - An Act regulating telecommunications facilities to support investigations. (Investigating and Preventing Criminal Electronic Communications Act.)

Legislative Renewal

In an environment where privacy issues are constantly evolving in the face of new technologies, it is critical to ensure that PIPEDA remains up to the task of protecting Canadians’ privacy rights.

Fortunately, PIPEDA (unlike the Privacy Act) requires review by Parliament every five years.

As a result of the first review, a number of amendments to PIPEDA were introduced in Parliament as part of two separate bills.

One of those pieces of legislation – a bill to fight electronic spam – received Royal Assent at the end of 2010 and will bring about important changes for my Office.

The aim of the legislation is to deter the most damaging and deceptive forms of spam and to help drive spammers out of Canada and stop them from preying on Canadians from abroad. Our Office will have a role in enforcement along with the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) and the federal Competition Bureau.

Included in the legislation are amendments providing our Office with a greater ability to share information with our international and provincial counterparts.

The same legislation also amended PIPEDA to provide the Privacy Commissioner with discretion to refuse or discontinue complaints. This is a welcome amendment which will help us target our limited resources to the most strategic issues for Canadians.

Going forward, we could decide not to accept a complaint if the complainant has not exhausted other available grievance or review procedures; if the complaint could be more appropriately dealt with under other federal or provincial laws; or if the complaint was not filed within a reasonable period of time.

Other amendments would provide the discretion to discontinue investigations. We could stop an investigation if, for example, there is insufficient evidence; the complaint is trivial or made in bad faith; the organization has provided a reasonable response; or the matter is already under investigation or has been investigated before.

We are required to provide the complainant and the respondent organization reasons for the refusal or the discontinuation.

Further proposed amendments to PIPEDA are included in the Safeguarding Canadians’ Personal Information Act, which was still before Parliament at the end of 2010.

That Act called for, among other changes, new requirements for organizations covered by PIPEDA to notify the Privacy Commissioner and affected individuals following serious data breaches.

The creation of a mandatory data breach notification regime would be an extremely welcome step for privacy protection in Canada. We are lagging behind many other jurisdictions, which already have breach reporting requirements in place.

Consumers should have the right to know if the personal information they entrust to an organization is disclosed without authorization, if there is a substantial risk of significant harm to their pocketbook or their reputation, business or employment opportunities, or creditworthiness.

Our Office would also be in a better position to ensure that all steps are taken to correct or mitigate the damage. And, over time, we would also be alerted to patterns and trends that require special attention so that the personal information of Canadians continues to be protected.

In 2010, our Office began preparing for the next review of PIPEDA, expected to begin in 2011.

We commissioned a report on the effectiveness of our current ombudsman model. As well, we held public consultations on the privacy issues related to both the online tracking, profiling and targeting of consumers by marketers and other businesses and cloud computing practices.

Both the report and the consultations will help inform our input during the upcoming review of PIPEDA.

Further information about our public consultations is included in section 2.

1.3 Supporting Organizations

Raising Awareness

In the fall of 2010, we officially opened an office in Toronto. Investigations concerning respondents in the Greater Toronto Area will be conducted from the new office and we will use our presence there to increase our engagement with businesses, industry associations and other stakeholders in the region. Our purpose is to enhance compliance with PIPEDA in the private sector through partnerships and education.

We also launched an enhanced online tool to help businesses protect their customers’ privacy. The tool helps businesses figure out how much information they should have about their customers and how to protect it.

Further information about our efforts to raise organizations’ awareness of privacy issues can be found in section 5.

Audit

One way in which we support compliance with privacy law by private-sector organizations is through verifying, through our Office’s audit function, that they have the policies, procedures and controls in place to safeguard the privacy and personal information of their customers.

In 2010, we conducted an audit of Staples Inc. Following previous complaints about breaches involving returned electronic data storage devices and considering the potential impact on consumers, we decided to examine the retailer’s personal information handling practices and procedures.

The audit, described in detail in section 3 of this report, showed that, while Staples generally has good privacy practices, the management of returned data storage devices is an area that is yet to be fully addressed. In 15 of the 17 stores audited, we found devices that were resealed and verified as wiped of consumer information when such was not the case; devices that were not verified by a manager prior to being restocked; or devices that were sent directly to a return to vendor bin without being wiped of consumer information.

We made a series of recommendations to Staples to help ensure it is meeting its obligations under PIPEDA.

1.4 Advancing Knowledge

Consultations

In the spring of 2010, we held public consultations on online tracking, profiling and targeting and cloud computing. We received numerous written submissions and held three public events in Toronto, Montreal and Calgary. The goal of the consultations was to learn more about certain industry practices, explore their privacy implications, and find out what privacy protections Canadians expect with respect to these practices. The consultations were also intended to inform the next legislative review process for PIPEDA.

We prepared a draft report that summarizes what we heard, what our views are, and how we see the road forward and published it for public comment. We will prepare a final report for publication in 2011.

Research

Research has become increasingly important in a world where complex technologies are raising new risks for privacy. Over the last couple of years, we have concentrated more resources on identifying and understanding the technological challenges to privacy.

In early 2010, we hired two highly qualified computer scientists and began equipping an internal lab to support their work. This investment supports two goals: building our in-house capacity to research developing technologies, and supporting investigations with a significant technological component.

We are continuing to expand the staff and equipment dedicated to this important function.

Contributions Program

Our Contributions Program continues to provide funding for cutting-edge research and public education in privacy promotion and protection. The program has provided over $2 million to more than 60 initiatives across the country since it was created in 2004.

In 2010, 16 projects received funding. Recipients are advancing research in a number of key areas of interest to the Office, including:

- Targeted online advertising;

- Data-sharing between governments and commercial organizations through national security programs at the border and at airports;

- Video surveillance in public spaces by commercial organizations; and

- The privacy implications of patient websites, online health record databases and other “Health 2.0” tools.

In the area of public education, the program is providing funding for projects aimed at informing Canadians on issues relating to credit ratings and privacy, and the impact of new information technologies on consumer privacy rights and protection.

Employee training

In response to the rapidly changing privacy landscape, our Office recognizes the importance of supporting training in the areas of leadership, management and specialist areas such as information technology and audit and investigation techniques. These competencies and specialized knowledge are required for achieving our mandate. In light of these requirements, we engage in activities to attract, develop and retain people with the aptitude and abilities to meet current and future organizational needs.

1.5 Global Initiatives

Privacy enforcement authorities worldwide are facing a similar challenge: How best to protect personal information that is constantly in motion across multiple jurisdictions.

Data protection authorities are increasingly recognizing that they cannot rely solely on national laws to protect data that doesn’t recognize borders. In 2010, we saw some important first steps towards establishing international cooperation frameworks.

Global Privacy Enforcement Network

Representatives from several privacy enforcement authorities came together at a meeting hosted by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) to launch the Global Privacy Enforcement Network (GPEN).

Our Office was one of the founding members. By the end of 2010, GPEN had more than 20 members on four continents.

GPEN is an informal network of privacy enforcement authorities that is intended to promote enforcement cooperation by sharing information about privacy enforcement issues and facilitating effective cross-border privacy enforcement in specific matters.

GPEN is an outcome of a 2007 recommendation of the OECD Council that called for the creation of a network of enforcement authorities. The recommendation was developed with the assistance of a volunteer group chaired by Commissioner Stoddart.

Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC)

The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Cross-border Privacy Enforcement Arrangement became operational in July 2010. Our Office helped develop the Arrangement and we are a participant along with the U.S. Federal Trade Commission and privacy commissioners from Australia, Hong Kong and New Zealand.

Like GPEN, the APEC Arrangement is intended to encourage information sharing but it is limited to enforcement authorities in the Asia-Pacific region and it is focused on more formal cross-border cooperation through parallel or joint investigations and enforcement actions.

Sharing Information with Global Counterparts

Effective enforcement requires being able to share information with other data protection agencies. Our ability to share information has been severely restricted but this has changed as a result of the passage of amendments to PIPEDA contained in anti-spam legislation which received Royal Assent in December 2010.

The amendments will give the Commissioner clear authority to collaborate and exchange information with foreign counterparts that have similar functions and duties, as well as with our provincial colleagues.

The information-sharing provisions in the new legislation strike a careful balance. We will only be able to share information under a written arrangement that limits the information to be disclosed and restricts how it can be used. The Commissioner will also be able to enter into arrangements to engage in other activities such as developing standards, conducting joint research and participating in staff exchanges.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has been a key player in developing global solutions to privacy and security issues. The efforts of the OECD Working Party on Information Security and Privacy are aimed at ensuring that the global flows of information are adequately protected and fostering cooperation among enforcement authorities.

The OECD Guidelines on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Data Flows celebrated their 30th anniversary in 2010. PIPEDA incorporates the Canadian Standards Association Model Code, which was largely based on the OECD Guidelines.

To mark the anniversary, the OECD held three special events. The first covered the development of the Privacy Guidelines, their impact in various countries, and the Guidelines in the current privacy environment. The second event was held in Jerusalem, in advance of the International Conference of Data Protection and Privacy Commissioners, and addressed the evolving role of the individual in data protection. The third event concerned the economics of personal data and privacy.

Commissioner Stoddart heads a volunteer group that helped plan the events. Our Office also seconded a staff member to the OECD to help draft a discussion paper describing the new privacy environment and identifying the challenges to protecting personal information in the 21st century. This paper, which is expected to be made public in 2011, is intended to serve as a background document for further discussion about how well the Guidelines are meeting current challenges.

The OPC, which works closely with the Government of Canada representative, Industry Canada, will continue to support the important work of the OECD, as it moves forward with an assessment of the Guidelines.

Ibero-American Data Protection Network

We have also intensified our relationship with the Ibero-American Data Protection Network. The network was created to foster the exchange of information among Ibero-American countries.

In September, Assistant Commissioner Bernier delivered the keynote address on Canada’s experiences during the first 10 years PIPEDA has been in force to the eighth Ibero-American Data Protection Meeting in Mexico.

Our Office closely followed the process leading up to the adoption of Mexico’s new private-sector privacy law, Ley Federal de Protección de Datos Personales en Posesión de Particulares, which was greatly inspired by PIPEDA.

International Organization for Standardization

The International Organization for Standardization, better known as the International Standards Organization or ISO, is a key player in the development of privacy-related standards for the use and deployment of new and existing technologies.

ISO's sub-committee on Information Technology Security – and, in particular, its working group on Identity Management and Privacy Technology – is a focal point for the development of privacy-related standards, including a Privacy Framework standard and a Privacy Reference Architecture standard.

A senior member of our Office acts as the Canadian Head of Delegation and national expert to this working group, as well as acting as the liaison officer from the International Conference of Data Protection and Privacy Commissioners to the working group. In addition to this role, he represents Canada on a high-level Privacy Steering Committee. This committee is working on a broad range of issues related to privacy terminology and privacy-related initiatives underway within ISO. It also organized the first international privacy standards conference, which was held in Germany in October 2010. The goal of the conference was to foster information sharing and coordination amongst ISO technical committees engaged in privacy standards work and other important stakeholders such as the OECD, APEC and international data protection commissioners.

Francophonie

Our involvement with the Association francophone des autorités de protection des données personelles (AFAPDP) continues to be an important focus of our international activities. The AFAPDP is the organization representing francophone data protection authorities around the world, and our Office was instrumental in its creation in 2007.

In 2010, Assistant Commissioner Chantal Bernier attended the association’s annual meeting in Paris, where she made two presentations. She discussed our Office’s experience with respect to new technological threats to privacy, notably in the online world, as well as the deployment of millimetre wave body scanners in Canadian airports. As well, she provided an overview of our Office as part of a discussion on best practices in data protection offices in francophone countries.

In future years, the AFAPDP plans to provide increased support to developing countries in the Francophonie as they establish new legislative frameworks to protect the privacy rights of their citizens. Our Office will strongly support these efforts.

Chapter 2

Key Issue: Privacy in the Online World

More than four of every five Canadians are now logging on to the Internet, the vast majority of them every day. They check the weather, arrange travel, chase after romance, shop, pay bills and taxes, watch videos, play games, hunt for information on products and services, and interact with friends, family and complete strangers.

The Internet is many things to many people: Convenient, comforting and familiar for some; a frustrating puzzle for others.

But what unites them all is that their online activities leave an unbroken trail of data.

Former Privacy Commissioner Bruce Phillips presciently raised concerns about this trail in his 1995-1996 annual report to Parliament, asking: “Nothing to hide? It's just as well...from the time we get up in the morning until we climb into bed at night we leave a trail of data behind us for others to collect, merge, analyze, massage and even sell – often without our knowledge or consent.”

Since then, the trail has only widened. It not only tells others where we have been and what we were doing; increasingly, it is being used to define who we are.

Over time, our online trail crystallizes into a highly detailed digital dossier that is of extraordinary interest to a whole lot of other people and organizations.

Governments, with an eye to public safety, troll the Internet for potential evil-doers.

Scammers and schemers see opportunities adorned with dollar signs.

Meanwhile, legitimate businesses are anxious to know what Canadians are up to online, in order to lure them with targeted ads and offers and to invest their marking budgets wisely. This can be welcome for people open to relevant information tailored to their interests. It can be intrusive for those who want to be left alone.

We live in what some have dubbed the era of “big data” – a global digital economy fuelled by massive international flows of data.

With advances in information and communication technologies and falling transmission and storage costs, these everyday transactions often result in multi-point transborder data flows.

Credit card purchases we make in another country using a card issued by a Canadian bank may be processed in a third country and data mined in a fourth jurisdiction.

With cloud computing, a Canadian-based company may use a web-based service provided by an American company to process and store personal information in multiple locations worldwide. This information, in turn, can be accessed by the Canadian company’s employees from any place in the world where a network connection is available.

The Internet, and technology in general, are evolving at a breakneck pace.

This rapid change, combined with the global nature of the issues and the fact that organizations and individuals are still struggling to develop the appropriate rules of engagement, make the task of protecting privacy in this still relatively new environment a significant challenge.

Our approach has been to address the privacy issues of the online world with tools such as investigations, research, outreach to business, public education and collaboration with international partners.

In 2010, we conducted several investigations into the privacy practices of online organizations.

Social media networks, which some research suggests now link together more than half of all Canadian Internet users, were of particularly pressing interest to our Office.

In 2010, we followed up on our landmark investigation of the world’s premier social network, Facebook, which we describe in section 2.1.

With Canadians increasingly likely to meet their romantic matches online, it’s no surprise that we also found ourselves investigating an Internet dating site – eHarmony.

We also investigated the U.S.-based Internet giant Google.

Specifically, we investigated Google’s collection of Wi-Fi data by vehicles gathering information for its Street View mapping function and found that the company had violated Canadian privacy law. We also publicly chastised Google for launching its Buzz social networking service without adequate regard for the privacy rights of its Gmail users.

Our message to all tech titans was clear: Think about privacy before you launch a new application; don’t just leave it to luck and the lawyers.

Through a groundbreaking series of consumer consultations last spring, we sought to get a handle on the privacy implications of certain emerging technologies, including cloud computing and the online tracking, profiling and targeting of consumers by marketers and other businesses.

Our consultations zeroed in on the privacy issues specific to children and youth, who are the most avid users of the Internet, especially social networking sites.

We also explored the issues in detail in our outreach activities involving schools. And we convened an advisory panel of teens from across the country to share their perspectives on digital privacy.

The Internet’s implications for privacy preoccupied us in other ways in 2010 as well. For example, in conjunction with a Government of Canada consultation paper on a Digital Economy Strategy for Canada, we reflected on the importance of digital literacy in helping people safeguard their privacy and anonymity online.

At the same time, we welcomed the passage of much-needed legislation to curb spam, bulk text messages and other forms of unwanted electronic communication. Spam carries threats such as spyware, malware and phishing attacks, thus undermining consumer confidence in the online economy. The new law, which received Royal Assent in December, gives our Office an enforcement role shared with the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) and the Competition Bureau.

It also makes some key amendments to PIPEDA. Notably, it gives the Privacy Commissioner greater discretion over which complaints to investigate, allowing us to focus on more complex or systemic issues. The Commissioner also gains more explicit authority to share information with other enforcement authorities, both within Canada and abroad.

In short, 2010 was a busy year for online privacy issues. The following describes some of the highlights of our activities in this area:

2.1 Facebook Follow-up

In the fall, our Office announced that we had completed a review of the changes that Facebook implemented as a result of our investigation of the site, and had concluded that the issues raised in the original complaint had been resolved to our satisfaction.

In a statement, Commissioner Stoddart said: “The changes Facebook has put in place in response to concerns we raised as part of our investigation last year are reasonable and meet the expectations set out under Canadian privacy law.”

The investigation, prompted by a complaint by the Canadian Internet Policy and Public Interest Clinic, a public advocacy group, resulted in significant change.

A major concern during the investigation was that third-party developers of games and other applications on the site had virtually unrestricted access to Facebook users’ personal information.

In response to our recommendations, Facebook rolled out a permissions model that is a vast improvement. Applications must now inform users of the categories of data they require to run, and to seek consent to access and use this data. As well, technical controls ensure that applications can only access user information that they specifically request.

Other changes provide users with clear information about Facebook’s privacy practices. The site developed simplified privacy settings and implemented a tool that allows users to apply a privacy setting to each photo or comment they post.

While we have closed the file on our original comprehensive investigation of Facebook, we have received further complaints about new issues. For example, we received complaints dealing with Facebook’s invitation feature and Facebook “Like” buttons on other websites. Those issues were still under investigation as we prepared this annual report.

Facebook Timeline

| May 2008 – Canadian Internet Policy and Public Interest Clinic files complaint. |

|---|

| July 2009 – Privacy Commissioner announces her investigation has identified a number of privacy concerns related to the Facebook site and that some of those issues remain unresolved. She asks Facebook to respond to those concerns within 30 days. |

| August 2009 – Facebook agrees to make a series of changes in order to address the Commissioner’s concerns. Facebook and the Commissioner’s Office set a one-year timetable for implementing these changes. |

| September 2010 – Privacy Commissioner announces that her review of the changes Facebook has implemented as a result of her investigation is complete and that the issues have been resolved to her satisfaction. |

| Current: Investigations into further complaints against Facebook are ongoing at the time of writing this report. |

2.2 eHarmony Investigation

Finding love and romance in the 21st century increasingly involves sitting in front of a computer screen.

The popularity of online dating sites has soared in recent years, joining introductions from friends and chance encounters in bars as one of the most common ways in which couples first meet. According to a statistic in the Harper’s magazine Index, the chance that an American couple who met since 2007 first met online is now one in four.

Meanwhile, the online dating industry’s revenues have been estimated at between $3 billion to $4 billion a year worldwide.

"It does seem to have displaced all other forms of dating…. I would say that it's been in the last five years that it's become hyper-mainstream,” Susan Frohlick, a University of Manitoba cultural anthropologist who has studied online dating, told the Washington Post in 2010.

Protecting privacy in the context of online dating sites – where so many people post so much personal information – has also become a mainstream issue.

It is in this context that we completed our first investigation of an online dating site’s privacy practices and policies in 2010.

eHarmony is a popular U.S.-based online dating site, which operates in Canada as eHarmony.ca.

To join the site, individuals must provide a substantial amount of highly personal information by completing a “comprehensive relationship questionnaire.” It includes more than 300 questions about everything from character, intellect, family background and income, to physical appearance and sexual vitality.

Complaint

A woman who had been a member of eHarmony complained to our Office that, upon ending her membership, she had asked eHarmony to delete her online account.

Days later, she went online to check that her instructions had been carried out. She discovered, however, that she could still sign in and that the account contained all the personal information she had previously provided.

She contacted eHarmony on several further occasions to repeat her request. According to the complainant, eHarmony replied that her account was now inaccessible to other members.

However, eHarmony told her that it could not entirely delete her record of having joined, or remove her personal information.

Dissatisfied with the response, she filed a complaint with our Office.

Investigation

When the complainant requested that the site “delete” her profile, she expected that her account and all her personal information would be permanently erased from eHarmony’s servers.

In response to her request, however, eHarmony initially “closed” – or deactivated – her profile, making it inaccessible to prospective matches.

The complainant quickly told eHarmony that this was not what she wanted. At that point, she learned from eHarmony that it did not permanently delete members’ personal information.

Our investigation found that the option to “close” an account was not readily accessible on the eHarmony website. Nor was there a clear explanation of what eHarmony meant by that term.

Moreover, there was no clear and separate permanent “deletion” option.

eHarmony stated that it “anonymizes” the information in the closed accounts as it eventually did in the complainant’s case, but did not explain under what circumstances it did so.

Data retention

PIPEDA requires that organizations develop guidelines and procedures with respect to the retention of personal information, as well as maximum and minimum retention periods. Under the law, eHarmony is allowed to retain personal information only for as long as necessary for the fulfillment of the purposes for which it was collected.

eHarmony stated that the reason it deactivated accounts and indefinitely retained the data – as opposed to deleting the accounts and the information in them – is that 40 percent of members reactivate within a two-year period. If the data is retained, individuals seeking to re-subscribe are not inconvenienced by the time-consuming task of completing a new questionnaire.

Recommendations

In our view, eHarmony should give users who decide to terminate their accounts a clear choice between account deactivation (temporary) and account deletion (permanent).

Further, it should make the distinction clear in its privacy policy.

During our investigation, we noted that if 40 percent of members tend to reactivate dormant accounts, then a majority – 60 percent – do not. Thus, they would not benefit from the indefinite retention of their information.

Therefore, we recommended that eHarmony:

- Develop, implement and inform users about a retention policy through which personal information in deactivated accounts will be deleted from eHarmony’s servers, erased or anonymized after a reasonable length of time;

- Include an account deletion option; and

- Explain to users on their member account pages how account deletion is distinct from account deactivation, making both options clear and easily accessible. An explanation of the difference between account deletion and account deactivation should also be written into the general privacy policy.

Response

In its response, eHarmony confirmed that it had taken, or was in the process of taking, steps to address our concerns, including:

- Establishing a two-year retention period for personal information that the site collects from the users of its service;

- Providing a clear and efficient process for users to request removal of their personal information; and

- Providing users with clear information about the difference between deactivating an account and deleting an account as well as information about how long eHarmony retains personal information.

eHarmony also explained to our Office how and when it anonymizes users’ data, which, in effect, permanently and irreversibly strips all personally idenfiable data from user accounts. eHarmony confirmed that the complainant’s account had been anonymized in this manner and the information was rendered permanently depersonalized.

eHarmony also advised our Office that it has revised and improved its procedures for responding to privacy requests.

Conclusion

Given that eHarmony now offers users a clear option of completely deleting their accounts before the end of two years, we concluded that a default retention period of two years for inactive accounts is acceptable.

Ultimately, we were satisfied with eHarmony’s responses. In addition to establishing a set retention policy, it has made its privacy controls clearer to users and improved processes for dealing with privacy concerns. Accordingly, the complaint was considered well founded and resolved.

Other observations

Concerns about privacy policies and practices related to the use, retention and disposal of personal information by online dating sites are by no means confined to eHarmony.

A quick scan of other sites reveals that some do not even have privacy policies. Some that have privacy policies do not specify how they handle personal information after a user is no longer active on the site.

Unless a site deliberately clears out personal data that is no longer required to support the user’s dating efforts, the information will remain on the servers. This introduces the risk of a data breach.

We urge users of any social networking site – and especially dating sites because of all the highly personal information collected there – to take steps to safeguard their privacy. For instance, users should:

- Make sure the site has a privacy policy and read the policy before signing up. The policy should be in clear and easy-to-understand language. It should state what types of personal information the site collects, how it is used, and how it will be protected.

- Check whether the site allows users to delete their profiles, and whether the deletion can be made permanent. Some sites allow users to “close” their account, but this merely deactivates it so it is not returned in a public search. The personal information remains intact on the database, possibly indefinitely.

- Check whether the site has a policy governing how long it retains personal information, and whether, when and how it deletes it. Some, for example, may only anonymize the data after a set period.

2.3 Google Wi-Fi

In October 2010, our Office published the results of an investigation into Google Inc.’s collection of highly sensitive data from unsecured wireless networks.

We found that the incident, in which Google Street View cars inappropriately collected personal information such as e-mails, usernames, passwords, phone numbers and addresses, was the result of an engineer’s initiative and Google’s lack of controls over processes to ensure that necessary privacy protections were followed.

We concluded that the collection was unlawful because it did not follow core principles of PIPEDA – user knowledge and consent to the collection of personal information. The incident was a serious violation of Canadians’ privacy rights.

Investigation

Our Office launched its investigation after Google admitted that its cars – which were photographing neighbourhoods for the Google Street View mapping application – had, over a period of several years, collected data transmitted over wireless networks. These networks, which were installed in homes and businesses across Canada and around the world, were not password protected or encrypted.

Technical experts from our Office travelled to Google’s premises in Mountain View, Calif., to examine the data collected. They conducted an automated search for data that appeared to constitute personal information.

To protect privacy, the experts manually examined only a small sample of data flagged by the automated search.

Even from that sample, it was clear that some of the captured information was highly sensitive. For example, one document listed people suffering from certain medical conditions, along with their telephone numbers and addresses.

Because the study was not intended to be comprehensive, it is impossible to say how much personal information was collected from unencrypted wireless networks. It is likely, however, that thousands of Canadians were affected.

Integrated code

Our investigation further revealed that Google collected the personal information because of a particular code integrated into the software used to collect Wi-Fi signals.

The code was developed in 2006 by an employee engineer who developed the code to sample all categories of publicly broadcast Wi-Fi data, and included lines that allowed for the collection of “payload data.” This term refers to the content of the communications.

Through a lack of control by Google to ensure proper safeguards were in place, the code wound up being used in the Google Street View cars when the company decided to collect information about the location of publicly broadcast Wi-Fi radio signals. This information was fed into its location-based services database.

When the decision to use the code was taken, the engineer who created it identified “superficial privacy implications.” Those implications were never assessed by other Google officials because the engineer failed to forward the code design documents to the Google lawyer responsible for reviewing the legal implications of the Wi-Fi project. This contravened company policy and controls were clearly lacking to ensure compliance.

Recommendations

In light of the investigative findings, the Privacy Commissioner recommended that Google ensure it has a governance model in place to comply with privacy laws. The model should include controls to ensure that necessary procedures to protect privacy are followed before products are launched.

The Commissioner also recommended that Google enhance privacy training to foster compliance among all employees. And she called on Google to designate staff responsible for privacy and compliance with Canadian privacy law.

She recommended further that Google delete the Canadian payload data it collected, provided this action is not prohibited by legal proceedings or other obligations under Canadian or American laws. Any Canadian payload data that could not be immediately deleted was to be secured and access to it restricted.

Google has responded to the Commissioner’s recommendations and the investigation was ongoing in early 2011 to ensure full resolution of the matter by Google.

Our Office was one of several international data protection authorities that investigated the Google WiFi incident. For example, the Spanish authority announced in late 2010 that it had opened infringement proceedings against Google, an action that could potentially lead to hundreds of thousands of Euros in fines. As we were preparing to publish this report, the French data protection authority announced it had imposed a fine of approximately $140,000 Cdn for breaching that country’s privacy laws.

Previously, Google had also raised significant privacy concerns in many countries, including Canada, with the launch of its Street View service.

2.4 Google Buzz

In April, Commissioner Stoddart and nine fellow data-protection authorities from around the world issued a joint letter that directed Google Inc. and other international corporations to respect the privacy rights of people who use their products and services.

The letter to Google’s then-Chief Executive Officer, Eric Schmidt, made public during a high-profile news conference in Washington, D.C., warned organizations to comply with the privacy laws of each country where they propose to roll out online products and services.

In an unprecedented collaboration, the privacy guardians – representing a combined 375 million people in Canada, Europe, New Zealand and Israel – expressed deep concern about Google’s privacy practices.

Central to the concern was the company’s launch, two months earlier, of a social network called Google Buzz. In creating Buzz, Google simply started with its Google Mail, or Gmail, service. Taking what had been a private, one-to-one, web-based e-mail service, Google automatically assigned users a network of “followers” from among people with whom they corresponded most often on Gmail. In many cases, this list of followers was made public.

However, those users were not adequately informed about how this new service would work, and were not given sufficient information to permit informed consent. This violated the globally accepted privacy principle that people should be able to control the use of their personal information.

Gmail users, understandably concerned that their personal information was being disclosed, sparked an intense backlash. Google apologized and quickly introduced changes to address the widespread criticism.

The data protection authorities, however, noted in their letter that the privacy problems associated with the rollout of Google Buzz should have been “readily apparent” to the company. They called on Google and other organizations entrusted with people’s personal information to incorporate fundamental privacy principles directly into the design of new online services, rather than to wait and test the product in the marketplace.

2.5 Anti-spam Legislation

As the year wound to an end, long-awaited anti-spam legislation received Royal Assent. The legislation regulates not only the sending of commercial e-mails and other forms of communications such as commercial text messages, but also other harmful practices such as electronic address harvesting and spyware.

Our Office had long supported such a law because unsolicited commercial e-mail violates the basic privacy principle of consent for the collection and use of personal information. Spam is also tied to phishing scams, identity theft and other privacy invasions.

In passing the legislation, Canada fell in step with all other G8 countries in addressing this assault on the online economy.

The new law will curb spam, including unwanted text messages and other forms of unsolicited electronic communications, by, among other things, strengthening consent requirements placed on senders.

Our Office will share oversight and enforcement powers with the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) and the Competition Bureau.

The Act reinforces our Office’s power to investigate the unauthorized collection of personal information through spyware or electronic address harvesting. The CRTC will guard against the sending of unsolicited commercial electronic messages, the re-routing of Internet communications without consent, and the installation of computer programs without consent. The Competition Bureau, meanwhile, will intervene in cases of misleading and deceptive marketing practices, including false headers and website content. Both of those institutions are empowered to impose significant penalties for individuals and organizations that violate the law.

To facilitate our Office’s co-operation with these two institutions, the legislation gives the Privacy Commissioner more explicit authority to share information with other enforcement authorities. This authority is broad, permitting collaboration on anti-spam and other matters with data-protection agencies elsewhere in Canada and abroad.

The new Act, expected to come into force in the fall of 2011, also gives the Commissioner more discretion to decline to investigate or to discontinue a complaint.

As 2011 got underway, we were working on developing an enforcement strategy, preparing tools to raise public awareness, and hiring additional staff to carry out our new responsibilities under the law.

2.6 Consumer Privacy Consultations

In the spring of 2010, our Office organized consultations on issues that we felt could test the privacy of consumers, now and in the near future. As people and businesses increasingly move online and enjoy the benefits of the digital age, the ways in which online sites use personal information in order to make a profit need to be fully examined from a privacy perspective.

We chose online tracking, profiling and targeting of consumers, and cloud computing, as our key topics, because we see these trends as likely to have impacts on the privacy of Canadians. We also focused specifically on children online.

The aim of this consultation was to learn more about certain industry practices, explore their privacy implications, and find out what privacy protections Canadians expect with respect to these practices.

The consultation was also intended to promote debate about the impact of technological developments on privacy, and to inform the next mandated review process for PIPEDA, scheduled for 2011.

We received 32 written submissions in response to our notice of consultations. We also held three webcast public events, in Toronto, Montreal and Calgary.

Online tracking, profiling and targeting

With respect to the consultations on online tracking, profiling and targeting, participants generally agreed on the issues, but less on possible solutions.

The blurring of public and private lives and the effect this has on people’s reputations was a major point of discussion. We heard concerns about children online. Children of all ages have a digital presence and their personal information needs to be protected. We heard about how privacy needs to be part of digital literacy or digital citizenship strategies.

Most industry participants maintained that PIPEDA is up to the task of protecting personal information in the face of evolving technologies and business models. Other participants were less definitive.

Examining online tracking, targeting and profiling through the lens of PIPEDA and the fair information principles, we noted the difficulties in determining what is and is not personal information. We also observed a lack of transparency around tracking, profiling and targeting, and what this means in terms of obtaining meaningful consent – a requirement under PIPEDA.

We recognize the work that industry associations do with their members in terms of helping them to be compliant with PIPEDA. Concerns were expressed during the consultations about what other new uses – besides behavioural advertising – could be made of individuals’ browsing activity or their social networking and location data.

We urge industry associations to continue reminding their members that consent to new uses is an integral part of privacy protection under PIPEDA.

There was a lot of discussion about the challenges facing individuals when online data about them is retained permanently. Our Office encourages industry to develop technical approaches to addressing retention issues.

In addition to retention, accessing one’s personal information and ensuring its accuracy are two important provisions in PIPEDA that can help address some of the reputational issues that stem from online activities. Our Office encourages industry to find innovative ways to meet the access, correction and accuracy provisions under PIPEDA.

Cloud computing

A second consultation topic was cloud computing, which refers to a growing trend to store data with third-party providers through an Internet connection.