Annual Report on the Privacy Act 2011-2012

This page has been archived on the Web

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

The Privacy Act 1982 – 2012

Three Decades of Protecting Privacy in Canada

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

112 Kent Street

Ottawa, Ontario

K1A 1H3

(613) 947-1698, 1-800-282-1376

Fax (613) 947-6850

TDD (613) 992-9190

© Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada 2012

Cat. No. IP50-2012

1910-006X

Follow us on Twitter: @privacyprivee

October 2012

The Honourable Noël A. Kinsella, Senator

The Speaker

The Senate of Canada

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A4

Dear Mr. Speaker:

I have the honour to submit to Parliament the Annual Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada on the Privacy Act for the period of April 1, 2011, to March 31, 2012. This tabling is pursuant to section 38 of the Privacy Act.

Sincerely,

(Original signed by)

Jennifer Stoddart

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

October 2012

The Honourable Andrew Sheer, M.P.

The Speaker

The House of Commons

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A6

Dear Mr. Speaker:

I have the honour to submit to Parliament the Annual Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada on the Privacy Act for the period of April 1, 2011, to March 31, 2012. This tabling is pursuant to section 38 of the Privacy Act.

Sincerely,

(Original signed by)

Jennifer Stoddart

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

About the Privacy Act

The Privacy Act, which took effect in 1983, obliges approximately 250 federal government institutions to respect the privacy rights of individuals by limiting the collection, use and disclosure of their personal information.

The Privacy Act also gives individuals the right to request access to personal information about themselves that may be held by federal government institutions. If individuals feel that the information is incorrect or incomplete they also have the right under the Act to ask that it be corrected.

Commissioner’s Message

The Evolution of Privacy Over Three Decades

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair …”

– Opening lines, A Tale of Two Cities, by Charles Dickens

When Canada’s Privacy Act was born 30 years ago, only a few people had even heard the phrase “surveillance society,” and even fewer were voicing concerns about its emergence.

To illustrate that concept, the first Annual Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada featured a cover cartoon of a man peering through a keyhole.

How innocent that seems in retrospect.

Who among us back then could possibly have dreamt of the pervasive surveillance of which government systems are now capable?

Who imagined video cameras would scrutinize people innocently going about their daily lives on a community’s main street? Or that scanning devices would peek through our clothes at airports? Or that the old-fashioned paper letters of that time offered more security from the prying eyes of the state than the electronic mail that would replace them?

The appetite of governments for personal information about citizens over the past three decades has proven to be voracious.

Time and again, Privacy Commissioners have raised red flags warning the public and Parliament about the risks of collecting too much information on citizens.

Over the years, a number of investigations by our Office have unearthed cases of denial of access or improper collection or disclosure.

A 2008 audit found that the Royal Canadian Mounted Police’s (RCMP) national exempt databanks (which are shielded from public access) were crowded with tens of thousands of records that should not have been there. Exempt databanks serve to withhold the most sensitive national security and criminal intelligence information, and yet more than half of the files examined as part of our audit did not meet the threshold for continued exempt bank status.

A decade earlier, when the federal air navigation system was privatized, the Office’s concerns about personal information being handed over by Transport Canada led to the culling of one million pages of outdated or irrelevant material – equal to standard file boxes piled 32 stories high.

Evolution of Privacy

The evolution of privacy issues during our first 30 years has been truly remarkable.

In 1982, when the Privacy Act was passed by Parliament, the country was two years away from the introduction of the first mobile phone. Electric typewriters still dominated in government and business. Visionaries were discussing something called the Internet.

The headline privacy issues of the 1980s reflected these simpler times.

When the personal information of about 16 million taxpayers was stolen from a National Revenue office in 1986 – “the Chernobyl of privacy disasters” we called it – the miniaturized details were recorded on rectangles of photographic film known as microfiche.

A prominent cause for complaints to our Office in those days were demands to produce a Social Insurance Number, which many people carried on a card in their wallet.

At the same time, however, new personal information concerns emerged; our Office flagged potential privacy risks from data matching, cross-border information flows, smart cards and genetics.

Together, the proliferation of low-tech privacy violations and the appearance of new threats combined to propel privacy “from a peripheral social issue, from being a rather esoteric, rarefied – almost cult – concern into the mainstream of public consciousness,” as the first Privacy Commissioner, John Grace, wrote in 1990.

This move into the mainstream was reflected in the Office’s workload, with many double-digit percentage increases in the number of complaints year over year during the 1980s.

And then things really got hectic.

Second Decade

The Privacy Act’s second decade, from 1992 to 2002, featured the emergence of increased risks to privacy stemming from the very nature of Canada’s fast-changing society – the explosion in computing technology, the increase in software sophistication and the transformation of personal information into a commodity.

The issues became more complex and mainstream consciousness was slow to awake to these risks. Public education became a high priority.

Our 1995-1996 Annual Report devoted two pages to describing the electronic trail of personal information that an ordinary Canadian unwittingly left behind during an average day in the brave new Information Society.

By then, Privacy Commissioner Bruce Phillips had abandoned his initial hope that voluntary measures by the private sector could effectively protect personal information. Instead he was urging the government to develop federal private-sector privacy legislation.

To the nation at large, Mr. Phillips also made an eloquent plea – one which has echoed down to the present – for Canadians to construct an ethical foundation for the new cyber technology. “Otherwise we are conducting a technical exercise in a moral vacuum,” he cautioned, “molding our lives to fit technology, not making technology fit our lives.”

The warning proved prescient.

Five years later, our 1999-2000 Annual Report revealed the hitherto unpublicized existence of a “citizen profile in all but name” created by Human Resources Development Canada.

An audit by our Office found that the innocuously named Longitudinal Labour Force File contained up to 2,000 items of information about individual Canadians, drawn from income tax returns, provincial and municipal welfare rolls, national employment services, child tax credits, the Social Insurance master file and elsewhere. Because records were never purged, the database included files on 33.7 million individuals, more than the total population then alive.

Within two weeks of the publication of that Annual Report, the government announced the database would be dismantled.

Mr. Phillips recalls that incident was “the biggest headline-grabber of my tenure” and also how Canadians were seized with the issue: “I think it generated tens of thousands of requests to the Department by Canadians wanting to know what this database contained about them.”

The privacy workload continued to mount, despite several consecutive years of severe constraint on resources.

Third Decade

The waning years of the second decade witnessed two developments that would have a significant impact on the third decade of our Office’s history.

First, the extension of our mandate to the private sector with the phasing in of the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) and, second, the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

The latter gave birth to a belief among Western governments that national security demanded the collection of more and more personal information about individuals – by open or surreptitious means – and required cross-matching that information across disparate databases.

Our 2001-2002 Annual Report highlighted what then Commissioner George Radwanski called a “Big Brother” database which would have retained for seven years as many as 30 pieces of personal information about all air passengers flying into Canada.

Fortunately, the next Annual Report was able to state that “our opposition, supported by public opinion, eventually led the Minister of National Revenue to revise the initiative, significantly reducing the impact on privacy.”

Meanwhile, national security concerns in the United States had a spillover effect in Canada.

The introduction of enhanced driver’s licences, which contain RFID chips that can be electronically scanned, is one of several instances where privacy issues have arisen because of U.S. national security initiatives.

Enhanced driver’s licences were proposed as an alternative to passports when the United States tightened its entry requirements. In 2007, the Canada Border Services Agency was working with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security to set up a system for using enhanced driver’s licenses at surface border crossings. During the program’s trial phase, the two agencies agreed that the data files of thousands of Canadians would be handed over to Homeland Security for storage in its database in the U.S.

Since 2002, the federal government has required that institutions carry out Privacy Impact Assessments for initiatives that raise privacy concerns.

While reviewing the Privacy Impact Assessment related to enhanced driver’s licences, our Office learned details of the plan; we then pointed out that the proposed data transfer was not only problematic for protecting the privacy of Canadians, but also unnecessary for the system to work.

As a result, when Homeland Security scans an enhanced driver’s licence today, its system pings a database in Canada, which allows access to verify only that one individual’s file.

Matters could have been very different if the Privacy Impact Assessment hadn’t been conducted. Had the wholesale export of personal information to the United States taken place as proposed, it might have been too costly to reverse.

A Tool with Impact

Later in this report, we provide more examples of the significant contribution of the assessment process to fostering a privacy-sensitive environment within the federal public service.

Another privacy protection measure which has amply demonstrated its worth in this tumultuous third decade is the detailed privacy audits we can carry out on government departments or programs.

While the Privacy Impact Assessment process is essentially preventative, the audits are remedial and identify systemic privacy issues, often after individual investigations have uncovered evidence of problems.

One such audit led to our first-ever special report to Parliament in 2008, mentioned earlier, about thousands of files containing personal information wrongly sequestered in RCMP exempt banks.

More recent audits have uncovered concerns related to the so-called “no-fly” aviation security program and the Financial Transactions Reports Analysis Centre of Canada (FINTRAC), the agency responsible for keeping tabs on possible criminal money-laundering.

Later in this Annual Report, we detail observations about the handling of personal information uncovered by an audit at Veterans Affairs Canada, already the subject of public criticism for violating a veteran’s privacy.

Other significant privacy concerns in recent years involve pending legislation to provide law enforcement authorities with stronger enforcement powers. “Lawful access” legislation, introduced in February 2012, proposes to create an expanded surveillance regime that would have serious repercussions for privacy rights.

Hope and Concern

In retrospect, the past three decades have been, as the opening Dickens quotation suggests, a time of both hope and profound concern on the privacy front.

On the hopeful side, despite the numerous issues that have come to light over the past three decades, privacy remains a treasured value for the vast majority of Canadians. In fact, a 2011 poll commissioned by our Office showed two thirds of those surveyed agreed that protecting the personal information of Canadians will be one of the most important issues facing the country in the next ten years.

By acting in an ombudsman role, our Office has achieved positive results in specific cases such as the enhanced driver’s licences, the Longitudinal Labour Force File and the protection of images captured by full-body airport scanners.

Despite some setbacks, the federal bureaucracy has generally become more attuned to privacy concerns.

Our Office is increasingly consulted in advance by government departments and agencies about the possible privacy implications of proposed initiatives, including in the highly sensitive area of national security.

However, some areas of outstanding concern remain.

Some are summarized in Chapter 3, which recounts our audit and investigations of Veterans Affairs Canada and investigations involving the Correctional Service of Canada and the Canada Revenue Agency.

As well, some departments are still taking far too long to respond to legitimate requests from individuals about their personal information on file – in the most extreme cases it can take years for people to gain access.

Finally, despite the risk of underscoring the obvious, I must pick up the theme of many previous Commissioners’ messages – the Privacy Act is badly outdated and requires an urgent overhaul to respond to the challenges of the digital era and the reality of huge government systems capable of a surveillance few could have envisaged in 1982.

Nonetheless, on this 30th anniversary, the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada has much to be proud of.

Our greatest asset over the years has been the dedicated and talented people who have devoted themselves to ensuring that the privacy rights of Canadians are protected. We have always been a relatively small team, but we have accomplished a great deal.

Since opening our doors, we have responded to some 260,000 requests for information from Canadians. We have completed 37,600 investigations. We have reviewed over 500 Privacy Impact Assessments since 2002 (when PIAs were introduced). And we have carried out approximately 150 audits of federal government institutions.

Most importantly, we have worked to make a difference for Canadians.

Jennifer Stoddart

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

A Brief History:

Federal Privacy Law and the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

The Parliament of Canada enacted the federal Privacy Act in 1982. Prior to that time, data protection provisions were included in the Canadian Human Rights Act.

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada opened its doors on July 1, 1983 upon the coming into force of Canada’s federal Privacy Act, which governs the personal information-handling practices of federal departments and agencies.

Over the three decades that have followed, we have adapted to a change in scope from purely public sector to private as well.

We have also gone from being heavily reliant solely upon investigations to focusing greater effort on public education to inform organizations on meeting their obligations through best practices and individuals on how to protect their privacy and assert their rights.

At the Office’s inception, it shared corporate management expenses with the Office of the Information Commissioner. The two offices combined for a total of 59 full-time employees and an annual budget of just more than $2 million.

Beginning in 2001, the duties of our Office were extended to the private sector under the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA). The legislation came into force in stages between 2001 and 2004.

By 2004, the Office no longer shared corporate management services and had an allocation for 100 full-time staff with a budget of just over $11.7 million per year.

In 2005, we received approval to stabilize funding for PIPEDA, as well as increased funding in support of our overall mandate. In subsequent years, we received additional funding for various initiatives such as the Federal Accountability Act, eliminating the backlog of investigations, expanding public outreach, establishing an internal audit function within the Office and also to support our new responsibilities under Canada’s anti-spam legislation.

In recent years, we have enhanced our ability to address the fact that so many new and developing privacy issues are tied to information technology and the online world. It is critical that we have the right expertise and tools to evaluate the privacy impact of various technologies.

The online world is global and over the past years we have also found that cooperation with data protection authorities in other countries is essential to protect Canadians’ privacy rights.

Today, the Office has the capacity for a full-time staff of 176 with annual expenditures of approximately $24.5 million. In response to the federal government’s Deficit Reduction Action Plan, our Office proposed that we would find savings of five percent per year within our operations by fiscal year 2014-2015 while maintaining the best possible level of service for Canadians.

Selected Quotes from Past Privacy Act Annual Reports

John Grace (Privacy Commissioner from 1983 to 1990) |

Privacy protectors cannot be staled by custom or allowed to be complacent. The challenges to privacy are new, urgent, various and ingenious, brought about by technology that never sleeps and is rarely denied. — 1984-1985 Before countries earn the right to preach about protecting privacy values in the flow of personal information crossing borders, they need to have adequate data protection laws within their own jurisdictions. — 1985-1986 |

Bruce Phillips (Privacy Commissioner from 1991 to 2000) |

There is no more fragile, yet important right, in today’s complex society than the right to a reasonable expectation of privacy. It is not a right, which some cynics suggest, that only serves those with something to hide. Without a meaningful measure of privacy our fundamental freedoms of expression, belief and association risk becoming meaningless. — 1990-1991 The technology is evolving so fast that neither engineers nor policy makers have time to consider the social impacts. Each new development affects or overrides the privacy protections so laboriously erected to defend against the last one. — 1991-1992 The information society could just as well be characterized as the information jungle where the prevailing law is the survival of the fittest. The jungle is about to become much more lethal to our privacy with the introduction of infinitely larger systems of collecting, manipulating and distributing our personal histories to countless others. — 1993-1994 |

George Radwanski (Privacy Commissioner from 2000 to 2003) |

We’re all confronted now with the real possibility of having to go through life with someone looking over our shoulder, either metaphorically or quite literally. …(T)he evolution of fundamental rights such as privacy should teach us that their greatest value lies in their ability to ensure and protect us in times of the worst adversity. — 2000-2001 The more information government compiles about us, the more of it will be wrong. That’s simply a fact of life. — 2001-2002 |

Robert Marleau (Interim Privacy Commissioner in 2003) |

People can have a private life even if much of their lives is spent in public view, as long as their activities cannot be linked to each other and to themselves. It is the ability to connect activities to each other and to an identifiable person that is at the heart of profiling and surveillance. Lost privacy cannot be given back. — 2002-2003 |

Jennifer Stoddart (Privacy Commissioner since 2003) |

Our Office is not convinced that reducing the freedom of all individuals in society will prevent further threats to public safety by terrorists. — 2003-2004 Characterizing the current (Privacy) Act as dated in coping with today’s realities is an understatement – the Act is tantamount to a cart horse struggling to keep up with technologies approaching warp speed. — 2003-2004 Canadians deserve real redress when things go wrong, not a Privacy Commissioner who has no power to even take a wrongful collection or a shameless disclosure of personal information to the Federal Court for a judgment and damages. — 2004-2005 There needs to be a greater acknowledgement of the fact that our privacy rights are fragile in the face of government. They falter each time we trade away the personal and private for promises of more safety, greater efficiency or faster service. The Orwellian dystopia was predicated on a totalitarian society. In our democracy, benevolent intentions appear to be pushing us toward a surveillance society. — 2007-2008 |

Privacy by the Numbers in 2011-2012

Information Requests

| Linked to the Privacy Act | 1 310 |

|---|---|

| Linked to the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) | 4 717 |

| Not linked exclusively to either Act | 3 086 |

| Total | 9,113 |

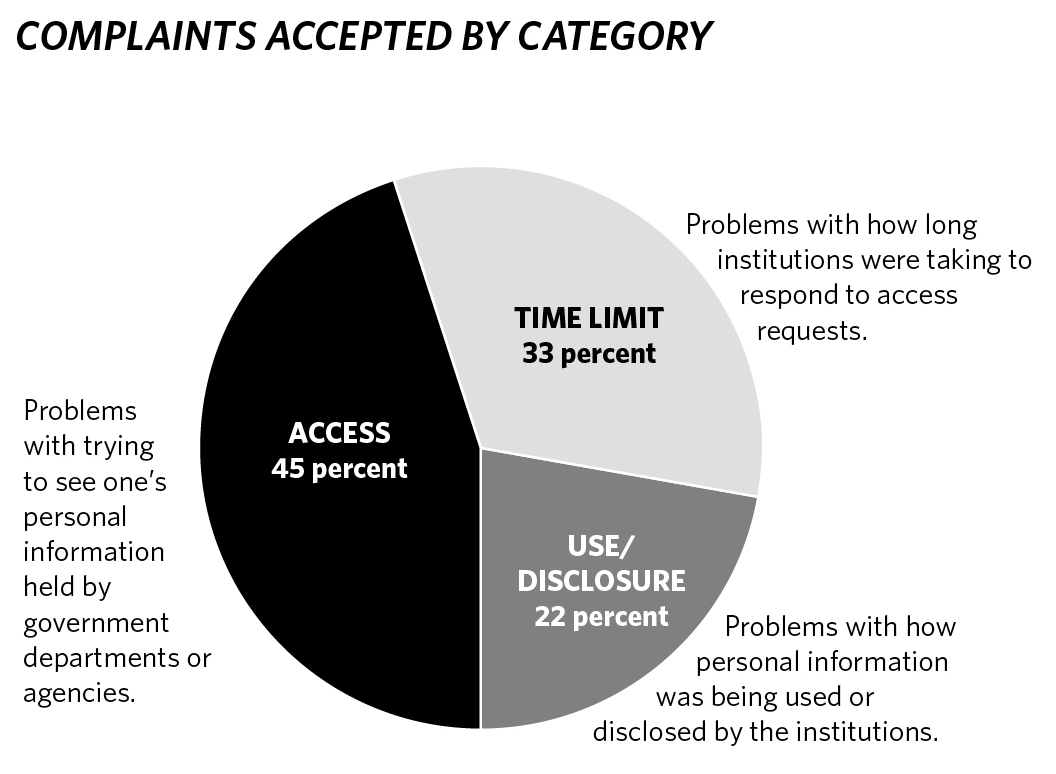

Privacy Act Complaints*

| Accepted | |

|---|---|

| Access | 442 |

| Time Limits | 326 |

| Privacy | 56 |

| Total accepted | 986 |

| Closed Through Early Resolution | |

| Access | 95 |

| Time Limits | 66 |

| Privacy | 213 |

| Total | 213 |

| Closed Through Investigation | |

| Access | 340 |

| Time Limits | 256 |

| Privacy | 104 |

| Total | 700 |

| Total closed | 913 |

| *For a description of each of these categories of complaints, please see Appendix 1. | |

Privacy Impact Assessment Reviews

| Received | 58 |

|---|---|

| Reviewed as high risk | 31 |

| Reviewed as lower risk | 26 |

| Total reviewed | 57 |

Audits

| Public sector audits completed | 1 |

Policy and Parliamentary Affairs

| Draft bills and legislation reviewed for privacy implications | 16 |

| Public-sector policies or initiatives reviewed for privacy implications | 54 |

| Policy guidance documents issued | 8 |

| Parliamentary committee appearances on public-sector matters | 5 |

| Submissions to Parliament | 2 |

| Other interactions with Parliamentarians or staff | 53 |

Communications Activities *

| Speeches and presentations | 138 |

| News releases and communications tools | 34 |

| Exhibits and other offsite promotional activities | 42 |

| Publications distributed | 13,351 |

| Visits to principal OPC website | 1.77 million |

| Visits to OPC blogs and other websites | 865,280 |

| New subscriptions to e-newsletter | 364 |

| Total subscriptions to e-newsletter | 1,365 |

| *Combined public and private sectors | |

Requests to the OPC under the Access to Information Act

| Requests received | 64 |

|---|---|

| Requests closed | 58 |

Requests to the OPC under the Privacy Act

| Requests received | 11 |

|---|---|

| Requests closed | 10 |

CHAPTER 1

The Year in Review: Key Accomplishments During 2011-2012

Here are highlights of the work we did over the past fiscal year to strengthen and safeguard the privacy rights of Canadians in their dealings with the Government of Canada. Details are provided in subsequent chapters.

Privacy Compliance Audits

During the year, we conducted an audit of Veterans Affairs Canada in order to assess compliance with the Privacy Act.

The audit found the Department has taken a number of encouraging steps and is determined to regain the confidence of its more than 200,000 clients after the highly publicized mishandling of one veteran’s most sensitive personal details.

Our Office’s 2010 investigation of that very high-profile case brought to light serious systemic issues and prompted the broader audit.

The audit, described in detail in Chapter 3, found that senior management at Veterans Affairs Canada is committed to ensuring that the personal information handling practices of the Department comply with the Privacy Act, and it has been actively involved in monitoring the efforts made to address the deficiencies highlighted in our investigation.

Key elements of a comprehensive privacy management program are now in place. As well, the Department is monitoring access to veterans’ files, refining system access controls and increasing employee awareness. It has also developed new policies, procedures, processes and guidelines to respect veterans’ privacy.

Information Requests, Complaints and Data Breaches

Our Information Centre is responsible for responding to requests from individuals and organizations about privacy rights and responsibilities - an extremely important service we offer to Canadians. In 2011-2012, we received over 9,000 requests and almost 15 percent of those related to federal public sector issues.

Meanwhile, there were significant increases in both the number of Privacy Act complaints accepted and closed. In 2011-2012, we accepted 986 complaints - an increase of almost 40 percent from the year previous. Meanwhile, we concluded 913 complaints – a 60 percent leap from a year earlier.

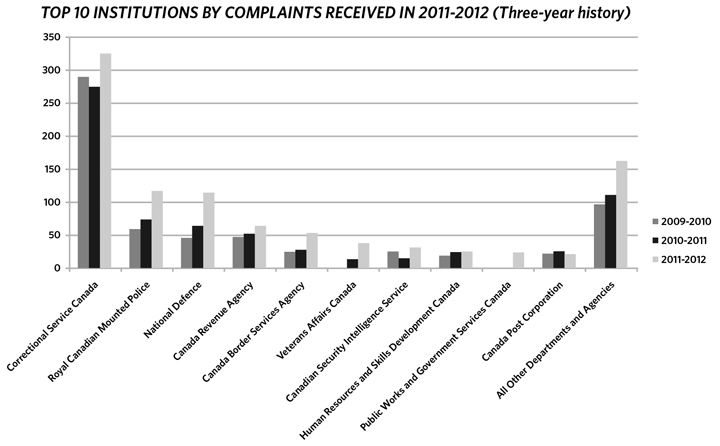

A significant proportion of the growth in complaints to our Office originated with four institutions: the Correctional Service of Canada, National Defence, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and Veterans Affairs Canada. We explore the reasons for these increases in Chapters 3 and 4.

Our use of early resolution has been growing steadily over the last several years. Early resolution can be used to effectively and quickly address some complaints by using negotiation and conciliation. In 2011-2012 almost a quarter of our closed files involved the use of early resolution.

Federal institutions reported 80 data breaches involving personal information in 2011-2012, the highest number of breach reports we’ve received in recent years. It is unclear whether the increase reflects more diligent reporting or an actual increase in incidents.

Privacy Impact Assessments

We reviewed 57 Privacy Impact Assessments (PIAs) in 2011-2012. Of these, 31 were reviewed in greater depth because of the significance of the privacy risks or the broader societal issues involved. Many of our PIA reviews and consultations with departments related to public safety initiatives.

Federal government institutions are required to undertake PIAs for activities and initiatives involving personal information, to demonstrate that privacy risks have been detected and either removed or mitigated. Our Office receives copies of these assessments; we may review and make comments on them if we feel it is necessary.

Policy and Parliamentary Affairs

Parliament had a reduced sitting schedule in 2011 as a result of the federal election in May. During 2011-2012, officials from our Office appeared five times before parliamentary committees and provided two written submissions, which is somewhat less than in previous years.

A number of the legislative and international initiatives the government embarked upon raised potential concerns for privacy – for example, the “lawful access” legislation (Bill C-30), the Canada-US Perimeter Security Action Plan, and the Safe Streets and Communities Act (Bill C-10).

Reaching out to Federal Institutions

Outreach is an important part of our interactions with federal government departments and agencies. Examples of our outreach during 2011-2012 included: hosting a third annual workshop for public servants on Privacy Impact Assessments, developing a video to help public servants to understand the PIA process; and helping to organize an event for federal Access to Information and Privacy professionals with our colleagues at the Office of the Information Commissioner of Canada.

Advancing Knowledge

The incredible pace of technological change makes our task of protecting the privacy rights of Canadians a constantly evolving challenge. It is essential that we take time to fully understand, and reflect upon changes that impact on privacy. Knowledge is what enables us to keep up with all this change.

At times, we commission research related to the public sector to support the work of our Office. In 2011-2012, this included work on themes such as privacy in the age of social media, surveillance and citizen journalism; the gathering of national security intelligence via the private sector; the proliferation of drones and the use of DNA for law enforcement purposes.

CHAPTER 2

The Integration of Privacy in Public Policy

A look at some of the positive developments for privacy protection within the federal government over the last 30 years.

Historical Look Back

From its very beginning 30 years ago, the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada has pursued the goal of nurturing a privacy-sensitive culture within the federal public service.

The ombudsman’s model for our Office and the absence of enforcement powers have dictated a collaborative approach to safeguarding the sensitive personal information of Canadians constantly being gathered by federal institutions.

With the support of many dedicated public servants, we have seen privacy steadily being integrated into the development of public policy throughout the past three decades.

That integration has gone through a few distinct phases.

Often, during the first 20 years, privacy was incorporated after a government initiative had been already put into action. Typically, a public complaint or an audit by our Office shone a spotlight on a privacy-invasive initiative and policy changes followed.

That happened with questions in the 1991 census about religion and fertility, which some Canadians complained were intrusive and which were withdrawn from the 1996 census.

We also saw a failure to consider privacy at the front end of an initiative with the Longitudinal Labour Force Survey, under which the then Human Resources Development Canada had quietly amassed files – some with 2,000 pieces of information – on 33.7 million Canadians (many of them deceased).

Two weeks after its existence was exposed in our 1999-2000 Annual Report, the Department shut down this “citizen profile in all but name.”

A second phase of integrating privacy in policy development began in 2002, when Treasury Board introduced the pioneering Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA) Policy.

Instead of the costly and cumbersome repairing of privacy transgressions after the fact, Privacy Impact Assessments are geared at prevention.

The TBS Directive on Privacy Impact Assessment (which replaced the former Policy in 2010) requires most federal government institutions to examine the privacy effects of new or significantly altered programs or activities. Departments and agencies need to determine what personal information will be collected.

When we review Privacy Impact Assessments, we look to see that federal institutions have demonstrated that there is a pressing and substantial public goal rationally connected to any activities that infringe on privacy.

We also expect empirical evidence showing how the proposed collection and use of personal information actually meets the needs of that public goal.

If privacy risks are identified, the PIA should describe and quantify those risks and propose solutions to eliminate the risks or mitigate them to an acceptable level.

The Government of Canada is a world leader in requiring federal institutions to undertake PIAs. Similarly, our Office is often consulted by international organizations and data protection authorities on our own process, which has developed and evolved over the past decade, for reviewing those PIAs. While institutions are not obliged to heed our advice, we find that most consider our recommendations and work with us to resolve or mitigate privacy concerns.

What began as a trickle (six PIAs in 2001-2002) has quickly swollen to a steady stream of assessments, which our Office handles on a triage basis, focusing on the initiatives which we believe pose the greatest privacy risks.

Between 2002 and the end of the 2011-2012 fiscal year, our Office has received a cumulative total of 588 PIAs, with 2009-2010 being the high water year with 103.

One notable success of the PIA approach involved the use of enhanced driver’s licences for land border crossings – a story told earlier in this report, in the Commissioner’s Message.

Our work on many other files has also had positive, privacy-protective results. A few examples are described below.

Privacy Impact Assessment Reviews: Making an Impact

Whole-body imaging at airports

Extensive consultations between our Office and the Canadian Air Transport Security Authority (CATSA) contributed to better privacy protections, including ensuring that millimeter-wave imagers were used only for secondary screening, and only as a voluntary option to a traveller undergoing a physical pat-down. (In some other jurisdictions, whole-body imaging is used for primary screening and is mandatory.) Scanned images are viewed in a separate area by an officer who cannot see the passenger. Follow-up checks by our Office have recommended better enforcement of these agreed-upon privacy safeguards.

Secure Certificate of Indian Status Card

First Nations citizens must have government-issued Indian status cards to claim entitlements under the Indian Act. A PIA submitted by Indian and Northern Affairs Canada in 2009 proposed that a new "secure" version of this card should also serve as a border-crossing document under stricter U.S. security rules.

This would have meant that all the application information for status cards would automatically be registered with Canadian border authorities, and potentially with U.S. border authorities. Instead, the Department accepted our recommendation to allow card holders the option of choosing border-crossing features, or having the status card issued without them, thus preserving their right to use a passport or enhanced drivers' licence instead, as do other Canadians at the border.

Automated licence plate recognition program in British Columbia

Active since 2007, the RCMP's automated licence plate recognition program in British Columbia uses video cameras on marked and unmarked police vehicles, combined with pattern identification software, to identify licence plates on parked and moving vehicles. More than 3.6 million plates were recognized in the first two and a half years of the program.

The plate numbers are cross-checked against databases containing lists of stolen vehicles, suspended drivers and uninsured vehicles. A "hit" or match triggers further investigation and police intervention; fewer than two percent of checks produce hits.

Our review of the PIA from the RCMP noted that the police were retaining the "non-hit" information. We saw that as ubiquitous surveillance of law-abiding Canadians who had committed no infraction. The RCMP agreed to stop retaining the "no-hit" information for the present.

Over the past few years, we have seen a promising new phase of policy integration unfolding.

We see a greater number of federal departments and agencies approaching our Office about initiatives or expanded activities even before they have prepared a PIA.

For example, the RCMP recently briefed us about a proposal to develop a centre to support investigations about missing persons and unidentified human remains.

In addition to a database accessible only to law enforcement agencies, the RCMP intends to create a public database with limited details about missing persons and unidentified remains.

Our Office reviewed with the RCMP concerns about data matching, limiting database access and the use of a public website to post details and solicit tips.

Such advance consultations span a wide range of programs - increased scrutiny of international students (Citizenship and Immigration Canada); developing international cyber security initiatives and protocols (Public Safety Canada); a cyber authentication renewal initiative, which includes using private-sector credentials to authenticate users of online government programs (Shared Services Canada); and a study of possible options for the 2016 census and beyond (Statistics Canada).

This dynamic integration of privacy in policy development has the potential to confer significant public benefits. It means that the public's privacy interests are taken into consideration at the earliest stages of developing policy for new programs. In turn, that should lead to speedier implementation of programs that are more privacy-aware.

Our process for reviewing PIAs is also evolving. Our Office is undertaking more site visits to supplement the paper-based review and is more frequently calling upon the expertise of our policy and technological specialists when reviewing PIAs. The help and collaboration of experts from other branches of our Office allows us to more effectively undertake complex and demanding examinations. In turn, our work on PIA files has helped to inform other branch activities, including parliamentary appearances, audits, inquiries, and complaint investigations.

Overall, PIAs provide our Office with an extremely valuable window through which we can view how initiatives are being rolled out across the entire federal government.

The Current Year

Privacy Impact Assessment Reviews

A thorough Privacy Impact Assessment can help ensure that the government collects only information to which it is legally entitled and which is necessary for a legitimate program, activity or initiative; that it properly protects the information; that it safeguards the information from inappropriate or illegal disclosures; and that it disposes of the information in a timely fashion when no longer needed.

We received 58 new PIAs during the past fiscal year.

Including some files submitted in the previous year, we reviewed 57 PIAs in 2011-2012. We sent out 31 detailed letters of recommendation for initiatives we felt were particularly intrusive, and an additional 26 letters with less detailed, high-level recommendations for initiatives which, in our view, posed lower privacy risks.

We also offered advice and recommendations at the request of government institutions on another 19 issues ranging from security clearance protocols to records storage and the use of personal information for social science research.

We welcome requests for these meetings and believe this consultative process is influential in helping to build data protection measures into government programs at the outset.

Here is a sample of these PIA reviews and consultations.

CITIZENSHIP AND IMMIGRATION CANADA

Visa Application Centre - Mexico

Citizenship and Immigration Canada consulted extensively with our Office on new requirements being introduced for temporary resident visa applicants, and on changes to the overseas application process. Staff at privately contracted visa application centres help individuals to fill in applications, provide information, verify that applications are complete and forward applications to Citizenship and Immigration for further processing and decision-making.

The way in which the Department establishes these overseas visa application centres is changing. Going forward, contracts with service providers will be managed by Citizenship and Immigration headquarters rather than by the Department's regional offices.

In some countries, applicants will be required to enroll their fingerprints at the visa application centre; these, along with a digital photograph, will be used to verify identity when the visa holder arrives at the Canadian port of entry.

We received a PIA for the Mexico Visa Application Centre in July 2011, and made recommendations about the collection of sensitive personal information by private sector contractors, as well as recommendations about the necessity to safeguard key documents. We also made broad recommendations for particular care in the safeguarding of fingerprints, which will be required for visa applicants from some countries, which are yet to be determined, starting in 2013.

We also raised questions about access to individuals' personal information by the governments of the countries in which the centres are located. We have asked that our Office be informed when the Department decides which countries must submit fingerprints for visa applications. We also requested that the PIA be revised to reflect the need for additional safeguards for the protection of sensitive biometrics.

To ensure that the independent service providers adhere to the privacy protection clauses in their service agreements, we recommended that Citizenship and Immigration regularly audit visa application centres. Citizenship and Immigration has indicated that it will do so, and that agreements may be terminated if service providers don't measure up.

ROYAL CANADIAN MOUNTED POLICE

Video Surveillance, Parliament Hill, Phase II

We reviewed a preliminary PIA on the expansion of video surveillance activities on Parliament Hill, which is a joint project of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and the security divisions of the Senate, House of Commons and Public Works and Government Services Canada.

Phase I of the video surveillance project was completed in 2003 with the installation of 50 cameras on the roofs of the Parliament buildings. Phase II contemplates the installation of an additional 134 video cameras over the next three years. The areas under camera surveillance include exterior perimeters of all buildings, pedestrian doors and assembly areas.

Some cameras will offer panoramic views and zoom capability and the video stream will be monitored 24/7.

We were concerned about the scope of the project and its potential impact on the privacy rights of Parliamentarians, Parliamentary staff, guests and visitors to Parliament Hill, and of those engaging in peaceful protests and assemblies. According to the preliminary PIA, a deliberate decision was made to not post signs notifying individuals of video surveillance on Parliament Hill.

That decision was of special concern to our Office. We referred the RCMP to our Guidelines for the Use of Video Surveillance of Public Places by Police and Law Enforcement Authorities, which state that the public should be notified by signage when surveillance cameras are in place.

We recommended that a full PIA be completed on the project, which will allow us to continuously assess future phases as they are implemented.

We also asked for a site visit to the video surveillance operations centre in order to observe collection, retention and disclosure practices. The RCMP responded positively, indicating they will share our concerns about signage with their partners in the project, and that a full PIA will be undertaken. A site visit was arranged, which added greatly to our knowledge and understanding of this project. We are in ongoing consultations with the RCMP, and will continue to follow this file closely.

National Victim Assistance Policy

The RCMP supplies police services under contract to all provinces and territories in Canada, except Quebec and Ontario. While the RCMP is subject to the Privacy Act, it also must respect provincial laws and policies where it operates.

One of the most interesting and challenging files during the past fiscal year involved the provision of personal information about victims of crime by RCMP members, working under contract to provincial governments, to provincially based victim services organizations without the consent of the victim - and, in some cases, when victims have specifically declined the service. This is known as "proactive referral."

While we recognize the importance of victims receiving the support and services to which they are entitled, we have several concerns about this practice when viewed through the lens of privacy.

We consulted closely with the RCMP and with provincial data protection commissioners during our review of this PIA, and a team from our Office visited victim services organizations in British Columbia. Our staff was impressed by the dedication of the victim services organizations to helping individuals whose lives have been affected by crime.

However, given the highly sensitive nature of the information being shared, and the applicability of the Privacy Act to the RCMP, we recommended that the RCMP reconsider the proactive referral policy. We also indicated that before personal information is shared with a third-party organization, the consent of the victim should be obtained.

When the victim does give consent, we recommended that the RCMP ensure victim services organizations have appropriate processes in place to guarantee the information received is protected and disposed of properly. We also recommended that the RCMP undertake regular audits to ensure these provisions are being met.

In addition, we suggested that the RCMP explore different and less privacy-intrusive methods of encouraging victims to give consent for referrals to victim services. This might include a targeted public outreach campaign in cooperation with provincial governments and provincial victim services organizations. We are continuing to consult with the RCMP on the issues raised by the PIA.

SHARED SERVICES CANADA

Access Key Service

We continued to review the Access Key Service, which is now under the responsibility of Shared Services Canada. The Access Key Service authenticates individuals and businesses in their online dealings with the Government of Canada.

We held numerous meetings with federal government institutions involved in this initiative, including Shared Services Canada and the Treasury Board Secretariat.

We have been assured that any federal government institution planning to offer online services or programs using the Access Key Service must first undertake a comprehensive risk assessment to ensure that the level of protection they will offer is commensurate with the risks and the sensitivity of the information involved in the online transaction.

We will continue to watch this file carefully as the government's online authentication renewal plan continues to evolve. The Access Key Service is to be phased out at the end of 2012, and will be replaced by a new Government of Canada branded credential. We will be reviewing a PIA for that initiative.

Credential Broker Service

In conjunction with the Access Key Service and as part of the federal government's Cyber Authentication Renewal Strategy, Shared Services Canada is introducing a new component of its service to authenticate Canadians when they use online government services.

The new Credential Broker Service, operating under contract to the government, will allow individuals to use online credentials issued by the private sector - such as electronic banking credentials - to sign onto Government of Canada services.

We have consulted closely with Shared Services Canada, the Treasury Board Secretariat and Public Works and Government Services Canada. We received a PIA on this initiative; however, it was lacking in required documentation and we asked that a revised PIA be submitted. Shared Services Canada agreed to do so. In the meantime, we continued our discussions, and have raised concerns related to the levels of authentication offered in the service and possible issues of accountability gaps if privacy breaches were to occur.

We have been reassured that appropriate mitigating measures are being built into the process and that privacy protective clauses are contained in the contracts between the federal government and the private-sector credential broker service.

CORRECTIONAL SERVICE OF CANADA

Disclosures for Health Research

The Correctional Service of Canada submitted a PIA about sharing the health information of inmates with Canadian academic institutions wishing to research the health of the federal offender population.

The PIA stated that this research is important to the safe transition of offenders into the community; to provide effective health services for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit offenders; and to improve mental health services. However, the file submitted to us lacked details on the actual research projects and did not include specifics of data-sharing agreements.

We had concerns about this vagueness, given the sensitivity of the information involved. We were also concerned that each unique research project may require different data elements and may create different technical risks.

We asked the Correctional Service of Canada to conduct separate PIAs for each data-sharing agreement. This will help ensure thorough analysis and mitigation of the specific and unique privacy risks that may be implicated in each research project.

We also asked that the agency carefully consider its proposed use of subsection 8(2(j)(i) of the Privacy Act for these disclosures. This section of the Act allows information to be disclosed for research purposes in an identifiable format only if the head of the institution is satisfied that the purpose for which the information is disclosed cannot reasonably be accomplished in any other manner. We are asking that the Correctional Service of Canada individually assess the merit of each research activity in order to make this determination.

CANADIAN AIR TRANSPORT SECURITY AUTHORITY

Passenger Behaviour Observation Pilot Project

Another significant review was the analysis of the Passenger Behaviour Observation pilot project, which was launched by the Canadian Air Transport Security Authority (CATSA) in 2011. The field trial took place over a five-month period from February to July 2011.This initiative involved specially trained officers who observed passengers awaiting clearance at the airport security checkpoint in order to look for suspicious behavior.

As we reported in our 2010-2011 Annual Report, our review of a PIA for Passenger Behaviour Observation raised concerns about the effectiveness of the initiative in identifying threats to aviation security. We noted the potential for inappropriate risk profiling, based on characteristics such as race, ethnicity, age or gender.

In addition to reviewing the PIA and consulting extensively with CATSA, we organized a site visit to see the project in action at the pilot site, Vancouver International Airport.

A PIA review officer and a technical analyst conducted a site visit in June 2011, and spoke at length with CATSA officials directly involved with the program at the airport.

The site visit added greatly to our knowledge of the initiative and helped us in our evaluation of the project's risks to the privacy and personal information of individuals.

We plan to increase our use of site visits in the future, as they have proven to be valuable adjuncts to the documents submitted to us for our review during the PIA process.

Parliamentary Activities

Another way in which privacy can be integrated into policy development is through exchanges and interactions between our Office and Parliament.

Our discussions and submissions can lead to substantive changes that offer better protections for the privacy of Canadians. Of course, Parliament decides if and how our contributions can best be utilized.

National security and public safety issues, including lawful access legislation and border security, loomed large during the year.

The 2011 federal election meant fewer sitting days for Parliament during the past fiscal year and, as a result, fewer formal appearances before Members of Parliament and Senators than usual for our Office.

The Commissioner and other officials from our Office appeared five times and we made two written submissions. Among the issues discussed were:

- The Safe Streets and Communities Act;

- Privacy implications of potential changes to the immigration system; and

- Proposed changes to existing legislation covering money laundering and terrorist financing.

The following highlights some of our parliamentary work in 2011-2012:

Lawful Access

The interplay between privacy and security is a fundamental question to any open, democratic society. Our Office understands the need and the importance of integrating privacy protections into public safety measures.

The Investigating and Preventing Criminal Electronic Communications Act (Bill C-30), introduced in February 2012, is but the latest incarnation of a longstanding project by authorities to recast Canada's legal framework regulating use of electronic surveillance.

Our Office has had a lengthy history with this effort and our exchanges with government on it extend back as far as the mid-1990s.

Our Office understands the challenges faced by law enforcement and national security authorities in fighting online crime - especially in an era of evolving communications technologies.

However, legislation that seeks to recalibrate police powers online must demonstrably help protect the public, respect fundamental privacy principles established in Canadian law and be subject to proper oversight. It is a standard of Canada's approach to surveillance that the invasiveness of a new police power or investigative method must be offset by similar levels of legal review, accountability and oversight.

Canadians care passionately about their right to privacy. Citizens from all walks of life, from every part of the country, irrespective of age and upbringing connect instinctively with this issue.

And so, when the government is proposing new methods of electronic surveillance - and contemplating the ideal balance between effective security and meaningful privacy - the views of citizens must be taken into account.

Since 2005, we have made our concerns public in parliamentary submissions and statements, responses to government consultations, communiqués issued with our provincial and territorial privacy counterparts, as well as in letters to responsible Ministers and lead departments. We have articulated these same concerns in speeches before professional associations, conference presentations, discussion papers and even classroom lectures.

In October 2011, we sent an open letter to the Minister of Public Safety to once again articulate our deep concerns prior to the reintroduction of legislation.

The proper treatment of personal information and the safeguarding of citizen's rights and freedoms in the context of national security are among the government's most pressing duties. Privacy protection is not an ancillary issue in this domain, but at the heart of the social freedoms that governments are bound to safeguard.

To date, Canadians have not been given sufficient justification for the proposed new powers when other, less intrusive alternatives could be explored. A focused, tailored approach is vital.

In February 2012, the federal government introduced the latest version of lawful access legislation, which proposes to expand the legal tools of the state to conduct surveillance and access private information.

For many years, our Office has been urging a cautious approach to creating an expanded surveillance regime that would have serious repercussions for privacy rights. We are not convinced that the latest bill takes the focused, tailored approach necessary to avoid the erosion of our free, open society.

We do recognize that the government, in that bill, reduced the number of data elements which could be accessed by authorities without a warrant or prior judicial authorization. There were also certain oversight provisions included in the latest version of the bill.

On balance, however, the legislation contains serious privacy concerns, similar to past versions.

In particular, we are concerned about access, without a warrant, to subscriber information behind an IP address. Since this broad power is not limited to reasonable grounds to suspect criminal activity or to a criminal investigation, it could affect any law-abiding citizen.

The ongoing privacy issues that remain outstanding include:

- The scope of the new powers, which can be accessed by a wide range of provincial and federal authorities;

- Access to personal information without judicial authorization, including instances unrelated to crime or security issues;

- The lack of public reporting, which lessens accountability and complicates Parliamentary review; and

- The absence of dedicated review, to properly control and check on the use of new investigative tools.

We look forward to sharing our detailed views on this bill with Parliament when Bill C-30 is studied in Committee.

Canada-U.S. Perimeter Security Action Plan

Another important public safety issue was the Canada-U.S. perimeter security initiative, the stated goal of which is to increase security and ease trade along our shared border. While details continue to emerge month by month, our Office has strongly advocated that all initiatives flowing from the agreement must truly and properly integrate and respect the privacy rights and legal protections expected by Canadians.

Prime Minister Stephen Harper and U.S. President Barack Obama signed the Beyond the Border Declaration in February 2011. Our Office subsequently participated in the government's public consultation and submitted a series of recommendations touching on the privacy risks stemming from the various elements of the perimeter security model. These themes included: guiding privacy principles, health emergency plans, cyber security, biometrics, traveller monitoring, information sharing and border screening measures.

Following those discussions, the Canada-US Perimeter Security Action Plan was released in December 2011.

This served to set the stage for our Office and our provincial and territorial colleagues to release a joint resolution on the initiative. The document stresses the importance of privacy protection in the new security initiatives and intelligence-sharing channels flowing from the governments' Action Plan.

In our recommendations to the federal government, we have stressed that:

- Any initiatives under the plan that involve the collection of personal information should also include appropriate redress and remedy mechanisms to review files for accuracy, correct inaccuracies and restrict disclosures to other countries;

- Parliament, provincial privacy commissioners and civil society should be engaged as initiatives under the plan take shape;

- Information about Canadians should be stored in Canada whenever feasible, or at least be subject to Canadian protection; and

- Any use of new surveillance technologies within Canada such as unmanned aerial vehicles must be subject to appropriate controls set out in a proper regulatory framework.

Our Office has already made provisions for the added review function and activities we anticipate in connection with the initiative's various new programs - reviewing Privacy Impact Assessments, offering comment on regulatory revisions and providing information to Parliamentarians on new legislative proposals and privacy issues flowing from the joint US-Canada security effort.

Safe Streets and Communities Act

The Safe Streets and Communities Act reintroduced a number of measures aimed at increasing penalties for certain crimes that had previously been included in nine bills debated by Parliament during a previous session, but not passed.

We advised Parliamentarians that the legal changes proposed in this omnibus legislation would have significant and lasting effects on privacy rights for many Canadians.

These effects are not limited to individuals convicted of criminal offences. For instance, people working at, or visiting a correctional institution, or married to or visiting certain imprisoned individuals could find their personal information collected more readily and shared more broadly among government agencies.

Our Office offered recommendations to mitigate potential violations of privacy and minimize unnecessary collection of the personal information of law-abiding Canadians. We cautioned government to establish robust controls and limits to narrow the collection, use, disclosure and retention of personal information to only that which is appropriate and necessary.

None of our recommendations were incorporated and the legislation received Royal Assent on March 13, 2012.

Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing

The Commissioner appeared before the Senate Standing Committee on Banking, Trade and Commerce on March 1, 2012, during its review of the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act.

During her testimony, she shared her concerns about a possible expansion of Canada's anti-money laundering and anti-terrorist financing regime without evidence that further changes were needed to address domestic problems.

Canada already has an expansive regime that, as we found in our 2009 audit, leads to the over-reporting of vast amounts of personal information about Canadians while failing to provide conclusive evidence about its effectiveness and its impact on Canadians.

The Commissioner recommended that the Senators fully assess the effectiveness of the regime and explore whether other measures could be more demonstrably efficient and less privacy-intrusive in combating money laundering and terrorist financing.

If the federal government is convinced that additional changes are absolutely necessary for law enforcement and national security purposes, the Commissioner underscored the importance of the government providing public justifications for these changes, supported by data and evidence. In 2012-2013 we plan to table our second audit of the Financial Transaction and Report Analysis Centre of Canada.

Security of Canada's Immigration System

The Commons Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration agreed in December 2012 to study the security of Canada's immigration system. Specifically, the Committee examined what gaps exist and the actions the federal government had taken or planned to take to enhance that security.

Appearing before the Committee on February 16, 2012, the Commissioner stressed that the Privacy Act imposes obligations when the federal government collects personal information. Federal agencies must ensure certain safeguards, limit secondary use, and list their data holdings publicly, whatever the citizenship of the individuals involved.

The Commissioner also told Committee members that if the federal government made any legislative or regulatory changes to the immigration system, she would expect detailed PIAs from the appropriate institution.

Finally, she emphasized the necessary tension between the scrutiny of visitors and Canada's global commitment to rights and freedoms. These values are embedded in the privacy obligations of government when it processes the personal information of individuals, either as they visit our country or take their first steps toward citizenship.

Census

Following the abolition of the Long Form Census, Statistics Canada consulted extensively with our Office on its Report on 2016 Census Options: Proposed Content Determination Framework and Methodology Options.

Statistics Canada explored methodological options for conducting the Census of Population in 2016 and beyond. These options, based on international practices, include the traditional census methodology currently used in Canada, the use of administrative records and surveys to supplement the short-form census and a census based on the creation of a Central Population Register using a universal PIN.

In our response, we indicated we could not support the use of a universal and mandatory PIN and a Central Population Register as a viable option. We also expressed strong reservations when it comes to the use of additional administrative data records for census purposes.

We continue to work with Statistics Canada.

CHAPTER 3

Challenges for Information Management

Three decades after the Privacy Act was passed, there remains room for substantial improvement in terms of how some federal government departments address the protection of personal information.

While there have been some very positive developments for privacy in the federal government over the past 30 years, some challenges remain.

This chapter describes some of the areas where there remains room for improvement.

Two themes are interwoven throughout the case studies that follow:

First, the need for improved anticipation of potential problems involving the management of personal information; and, second, the need for better training in how to reduce those risk areas.

For example, better training should have led correctional officers to question the propriety of posting inmate medical appointments in plain view at a federal penitentiary. Who amongst us wants our co-workers (or fellow inmates, as the case may be) to know, not only when we're seeing the doctor, but even the purpose of the visit? Similarly, a lack of awareness of procedures led officials to, not once, but twice, wrongly reveal the severity of a disability suffered by a member of the Canadian Forces to people who had neither the need, nor the right to know.

However, clear direction from the top and a well-conceived training and communication plan can make a huge improvement in privacy awareness and in the management of personal information.

Our exhaustive audit of Veterans Affairs Canada paints an encouraging picture of a Department determined to regain the confidence of its more than 200,000 clients after the highly publicized mishandling of one veteran's most sensitive personal details.

This chapter also shines a spotlight on two other departments which have consistently been on our Office's Top Five list for complaints over the last decade - the Correctional Service of Canada, which is in a league of its own in terms of the volume of complaints to our Office, and the Canada Revenue Agency.

There are intrinsic reasons why certain federal institutions are liable to continue to generate a substantial number of Privacy Act complaints. They hold a huge volume of personal information, much of it highly sensitive.

However, there are also ongoing privacy concerns related to those two institutions. In some cases, a genuinely proactive approach could lead to stronger privacy management and thus, fewer complaints.

Data breaches remain another source of continuing concern. The number of breaches reported to our Office last fiscal year hit an all-time high.

As examples demonstrate, many of those breaches could have been avoided by the exercise of some common sense. And others could have been averted if people had followed existing rules.

Finally, endlessly delaying access to personal information is no different than refusing access outright. That was the intended message when Parliament included a maximum time limit of two months for responses to requests made under the Privacy Act.

Yet this deadline is too often missed. In some cases, delays have even stretched into years.

An Audit of Veterans Affairs Canada

Background

In October 2010, the Commissioner released the results of an investigation into a complaint alleging that Veterans Affairs Canada mishandled an individual's personal information.

The investigation brought to light serious systemic issues, prompting our Office to launch the audit of Veterans Affairs.

The investigation found that the veteran's sensitive medical and personal information was shared - seemingly with no controls - among departmental officials who had no legitimate need to see it. This personal information subsequently made its way into ministerial briefing notes about the veteran's advocacy activities.

The investigation confirmed that two ministerial briefing notes about the complainant contained personal information that went far beyond what was necessary for the stated purpose of the briefings. This included sensitive medical information as well as details about how the complainant interacted with the Department as a client and an advocate for veterans.

The Commissioner concluded that the Department was not compliant with the Privacy Act and lacked adequate controls to safeguard the personal information of veterans.

The Commissioner recommended that Veterans Affairs:

- Develop an enhanced privacy policy framework to regulate access to personal information within the Department;

- Revise information management practices and policies to ensure that personal information is shared within the Department on a need-to-know basis;

- Ensure that consent for the transfer of personal information has been obtained and that the information shared is limited to that which is necessary; and

- Provide training to employees on how to handle personal information.

In response to the Commissioner's report, and at the request of the then Minister of Veterans Affairs, the Department developed a 10-point Privacy Action Plan to address these recommendations.

As part of this plan, the Department:

- Implemented a privacy governance structure;

- Developed policies, procedures, processes and guidelines for managing veterans' personal information;

- Established mandatory privacy training for employees; and

- Instituted monitoring of the Client Service Delivery Network, the primary electronic repository for veterans' personal information.

About Veterans Affairs Canada

Veterans Affairs Canada provides programs and services to more than 200,000 clients, including veterans from the Second World War and Korean War as well as former and serving members of the Canadian Forces and eligible family members. The Department also administers disability pensions and health care benefits for certain serving and former members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

With approximately 3,900 employees, Veterans Affairs operates three regional offices and 35 service points across Canada. The Department has also established 24 integrated personnel support centres with the Department of National Defence.

More information is available at www.veterans.gc.ca.

What We Examined

We reviewed the Department's personal information management policies, procedures and processes, program records, guidelines, Privacy Impact Assessments, security reviews, training materials, information-sharing agreements and contracts with third-party service providers.

We also examined the controls in place to protect personal information stored in electronic and hard copy format. In addition, we looked at a sampling of veterans' files.

The objective was to assess whether the Department has implemented adequate controls to protect the personal information of veterans, and whether its policies, procedures and processes for managing such information comply with the fair information practices embodied in sections 4 through 8 of the Privacy Act.

The audit did not include a review of the Department's management of personal information about its employees or contract personnel or the programs administered for the RCMP. Nor did we examine the personal information handling practices of the Veterans Review and Appeal Board, the Office of the Veterans Ombudsman, the Bureau of Pension Advocates, Ste. Anne's Hospital or the Department's third-party service providers.

Why This Issue is Important

The Department offers a wide range of programs and services to veterans, their dependents and survivors. This requires the collection and use of sensitive personal information and the maintenance of a large repository of that information.

The data holdings are not only voluminous, they are also highly sensitive. In addition to biographical data (names, dates of birth, marital status, etc.), veterans' files may contain military service records, employment and educational histories, financial and medical information.

The unauthorized use and disclosure of personal information could have a significant impact for veterans, their dependents and survivors. This could include financial loss resulting from identity theft or fraud, humiliation or damage to reputations, or risk to personal safety.

Veterans Affairs Canada has a legal obligation to ensure that policies, procedures and controls are in place to protect personal information collected under its mandate. This is essential in order for the Department to maintain the confidence of veterans in its ability to preserve the confidentiality of information entrusted to it.

What We Found

Senior management at Veterans Affairs Canada has expressed a commitment to ensure that the personal information handling practices of the Department comply with the Privacy Act, and it has been actively involved in monitoring the efforts made to address the deficiencies highlighted by the Privacy Commissioner in October 2010.

Key elements of a comprehensive privacy management program are in place.

An internal governance structure has been formalized to foster a culture of privacy throughout the organization, and to provide a coordinated and consistent approach to managing privacy in day-to-day operations. Information management and privacy experts have been engaged to examine and identify opportunities for improving the Department's personal information management practices.

As well, investments have been made in monitoring access to veterans' files, refining system access controls, increasing employee awareness, and developing new policies, procedures, processes and guidelines to respect veterans' privacy.

Our 2010 investigation report centred on two ministerial briefing notes containing personal information beyond what was necessary for the stated purpose of the briefings.

Within a month, the Department established guidelines for preparing briefing notes and other documents for internal use, as part of its Privacy Action Plan.

The guidelines emphasize that briefing material should contain only personal information that is absolutely necessary to meet the objective of the briefing. Employees are also instructed to consider whether this objective can be achieved without including personal identifiers, such as the names of veterans.

Employees involved in drafting client-specific briefing notes and background reports received training on the new guidelines. The Department also established centralized work units to process ministerial briefing documents.

As part of our audit, we reviewed a sample of 88 client-specific ministerial briefing documents that were prepared between April 2011 and March 2012.

We found that virtually all of them adhered to the need-to-know principle - the personal information revealed was limited to that necessary to fulfill the purpose of the briefing.

While two briefing documents contained information that extended beyond what was strictly required, it should be noted that those particular documents were prepared before a quality assurance process was set up in the fall of 2011.

Fair Information Practices

Fundamental to privacy protection is the principle that personal information should be collected only if there is a legitimate and authorized need directly related to an operating program or activity. We found that the Department's collection activities are relevant and are not excessive, and that veterans' personal information is used for authorized purposes.

However, there is room for improvement in how the Department manages veterans' consent. Generally, the Department obtains consent before releasing a veteran's personal information to a third party (e.g. external service provider, family member, etc.). But we observed consent forms that did not specify the third party or the information the Department was authorized to release. Further, we noted disclosures had been made and the corresponding consent was not included in the file.

Similarly, we found that details surrounding consent were not always entered in the Client Service Delivery Network, the primary electronic repository for veterans' records. A concerted effort is needed to ensure consent is consistently and sufficiently recorded on file. Otherwise, there is a risk that the Department may mistakenly disclose veterans' personal information.

We recommended that Veterans Affairs Canada ensure that veterans' consent is consistently recorded on file, and is easily accessible for verification. We also recommended that the Department establish mechanisms to provide assurance that consent is accurately reflected in the Client Service Delivery Network.