Privacy and Developing Countries

This page has been archived on the Web

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Dr. Gus Hosein

Visiting senior fellow at the London School of Economics and Political Science

This report was commissioned by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

September 2011

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Aaron Martin for his research support on this paper, and the helpful reviews and support from Laurent Elder at the International Development Research Centre. Maria Yalamova was essential in assisting on the research, and David Banisar and Edgar Whitley for their constant flows of helpful information sources, and the earlier work of Nicholas Pauro. This report relied heavily on the feedback from our research partners on the PrivAsia project, including Al Alegre, Shahzad Ahmad, Jehan Ara, Vickram Crishna, Nighat Dad, Kerina Francis, Nagarjuna G., Rajan Gandhi, Elonnai Hickok, Prashant Iyengar, Ahmed Swapan Mahmud, Pirongrong Ramasoota, Phet Sayo, Dinesh Thapa and Nigel Waters. I am also grateful for the insightful research from Jeremy Gruber and Helen Wallace, and the ever-valuable insight from Simon Davies.

I. Introduction: Privacy for the other five billion

Privacy and surveillance is quickly climbing the policy agendas of developing countries. This study will review this landscape by identifying some of the leading policy initiatives and how they are considered in developing countries.

Biometric systems, DNA databases and communications surveillance have all given rise to significant parliamentary debates, policy campaigns, legal processes and research studies in the course of the last decade. When these policies are introduced, democratic deliberation usually follows, lobbying and advocacy ensues, media organisations become aware of the issues and, in turn, give rise to greater awareness-raising campaigns. As a result, laws are amended, systems are implemented with regulators and agencies to oversee the process, and courts may be called upon to judge compliance with constitutional provisions. This is the ideal policy life cycle in a deliberative democracy.

Except this rarely occurs. While we are finally seeing advanced and sophisticated debates in some countries, the vast majority of countries around the world do not yet have these debates over matters relating to privacy. Understandings of technology may be more limited. Advocacy groups, media organisations, regulators, and judiciaries, where they exist, are less equipped to engage in these complex technology policy discussions. Even the policy-makers themselves may be unable to cope with the complexities.

This is particularly the case in developing countries. Neither the lack of debate nor their weaker economic status as ‘developing countries’ affects the rate of adoption of surveillance policies. In fact, as this report will show, many developing countries are implementing vastly more sophisticated surveillance systems than exist in the developed world. The rate of adoption of these policies and technologies is increasing dramatically.

By reviewing some of the exemplary surveillance practices, this report will identify some of the key dynamics in these policy processes. There may be opportunities for the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada to help build capacity on these issues globally. In turn, there may also be opportunities for us to learn from these dynamics that may inform our own policy processes in ‘developed’ countries. Many of the policies in the developing countries that are outlined below may be signs of things to come.

Methodology

This report is a summary of the author’s in-depth research over the past three years. In that period I have conducted a number of reviews and studies on privacy issues in developing countries and emergency situations. These include:

- Co-ordinating a project with the International Development Research Centre (IDRC)Footnote 1 on privacy rights in Asian developing countries. This ongoing project, funded by IDRC, has partners from 8 Asian economies (Bangladesh, Hong Kong, India, Malaysia, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Thailand).Footnote 2

- Advising the International Development Research Centre on its approach to 'eHealth' systems in developing countries and emergency situations by highlighting the risks to information security and patient privacy.Footnote 3 The research was informed through interviews and meetings with practitioners and experts from around the world, including Haiti, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, Rwanda, and South Africa.

- Advising the United Nations (UN) Special Rapporteur on Terrorism and Human Rights in his 2010 study on the implications of anti-terrorism policies on privacy rights around the world.Footnote 4

- Acting as an external advisor to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in an evaluation of biometric registration of refugees, with on-site work in Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya and Malaysia. This was partly funded by IDRC.

This report also builds on data collected over a longer period of monitoring international developments within my work at Privacy International. Along with colleagues at the London School of Economics and Political Science, notably Aaron Martin who contributed to the research for this report, we have been monitoring legal, policy, technology and research developments around the world.Footnote 5

The ideas in this report are also a representation of the findings of a workshop I recently chaired in the Philippines amongst privacy experts from Asian developing economies. I asked the participants from 10 countries in the region about the links between privacy and development, and the challenges therein. Their answers informed this work and were a useful sounding-board for the ideas presented below.

II. Human Rights, Privacy, and Development

Even as surveillance rises on the policy agendas in developing countries, there are some significant obstacles to raising the profile of privacy and human rights.

Establishing policies on surveillance and privacy already pushes the limits on democratic deliberation and debate. 'National security' and 'anti-terrorism' are merely components of the constellation of arguments around privacy and surveillance policies, as they do battle with concerns about efficacy, effects on personal liberty, implications on economic strategies and business models, and consumer protection. Technology, meanwhile, both aids and inhibits all these arguments as we struggle to understand what is possible, cost-effective, legal, and justifiable.

It is only recently that we have started incorporating rights considerations into our policy deliberations. As a result in recent years there have been extensive debates and deliberations on some surveillance policies. To name a few:

- biometric and genetic databases in the United Kingdom led to these issues becoming key constitutional, political and electoral issues;Footnote 6

- communications data retention in Germany has resulted in years of controversy, legal cases involving over 34,000 complainantsFootnote 7 and marches on the street;Footnote 8

- lawful access to communications in Canada has taken years to establish because of political uncertainty;

- smart-meters in the Netherlands faced significant resistance which forced policy change;Footnote 9

- the powers of state security agencies in the United States continues to be questioned in the courts,Footnote 10

amongst many others. The outcomes have not always favoured privacy, but the traditional policy process has been used to its fullest: parliamentary debate, policy research, media campaigns, lobbying and other activities by all sides of the debates, court cases and appeals. We can speak of ‘rights’ to privacy, and demand that ‘interferences’ are consistent with international conventions and national constitutions.

There are essential conditions for such deliberations to take place. Constitutional rights and international treaty obligations are essential for appeals to the judiciary. Laws and regulations are necessary to provide key junctures in legislative processes. An active and resourceful civil society is often necessary in order to raise attention and bring cases to regulatory and judicial bodies. An independent and interested media that is open to questioning state power and national security interests can provide a forum for calling authorities to account.

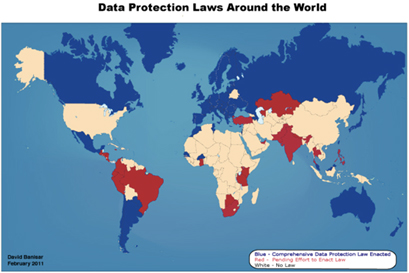

In the field of privacy, these conditions exist only in a few countries. Many countries, if not most, have treaty obligations and constitutional articles but often lack the key institutions such as a well-resourced civil society, regulatory institutions, an independent judiciary, and active and informed media organisations. Even as an increasing number of developing countries are establishing data protection laws, they frequently lack the capabilities to regulate.

The lack of appropriate resources and institutions may lead one to conclude that developing countries may not have an active interest in privacy protection. Even the emergence of national data protection laws is seen by critics merely as an attempt by the government of a developing country to attract investment from Europe, and not some national initiative based on a sense of urgency and need.

Such criticism is not dissimilar to the criticism that emerges in debates around Development and Human Rights.Footnote 11 When applied specifically to privacy, these include concerns about universality and cultural sensitivities, the prioritisation of human rights over development, and whether privacy is only of concern in advanced technological and consumer-based economies.

A 'universal right' or 'cultural imperialism’?

Human rights proponents are sometimes painted as universalists who ignore local cultures. According to opponents of universalism, some cultures do not have a regard for individual rights but rather wish to promote the group or community’s rights first. Therefore, human rights are foreign concepts pushed upon unwilling nations and cultures.

Human rights proponents argue that this is not at all the case; the inviolability of the human’s rights to be free and deserving of dignity is core to what it is to be human. Additionally, every country around the world has signed on to at least one of the UN’s seven core human rights treaties. To these universalists, ‘culture’ arguments are often excuses against change. Culture is neither static nor sacrosanct and so can not inherently be incapable of considering new ideas. The universalists do acknowledge that culture may affect the practical implementation of human rights.

The cultural argument is frequently used against the implementation of privacy rules: ‘privacy is a Western value’, foreign to many countries and cultures. Cultural relativists argue that many countries and cultures can choose to ignore privacy rights in favour of group rights, the needs of the public, and the needs of the state. International human rights norms should not interfere with a given society’s ability to choose how and when interferences with the ‘right’ to privacy can be undertaken. After all, where there is strong trust and confidence in the state or in market actors, why should strict lines be drawn by foreign dictation?

Nearly all international declarations of rights include explicit protections for privacy. Article 12 of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights 1948 declares the right to be free from arbitrary interference with one’s privacy, home or correspondence. Similar language is enshrined in Article 17 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1966, Article 14 of the UN Convention on Migrant Workers, and Article 16 of the UN Convention of the Protection of the Child. A number of regional human rights charters and conventions recognise the protection of privacy, including Article 10 of the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, Article 11 of the American Convention on Human Rights, Article 4 of the African Union Principles on Freedom of Expression, Article 5 of the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man, Article 21 of the Arab Charter on Human Rights, and Article 8 of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms.

Mere signing of an international treaty does not necessarily mean that an entire nation subscribes to all the rights therein. A national commitment may be better confirmed through its constitution. In some countries the right to privacy emerged from the right to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures, as well as the rights to free expression and due process. In other countries the right to privacy emerged as a religious value.Footnote 12 Privacy is also considered core to governments’ responsibilities to protect human dignity and the right of personality. In our reviews of privacy developments around the worldFootnote 13 we found that outside of the ‘West’Footnote 14 privacy is prevalent within constitutional statements:

- Explicit statements about the right to a private life, secure from unwarranted search and seizure, and communications surveillance clauses exist in one way or another in constitutions from countries as diverse as Angola, Algeria, Argentina, Bangladesh, Bolivia, Brazil, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Chile, China, Colombia, Comoros Islands, Republic of Congo, Costa Rica, Djibouti, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Egypt (earlier and current), Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Guatemala, Guinea-Bissau, Jordan, Kenya, Mongolia, Pakistan, Philippines, Peru, Paraguay, Russia, South Africa, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda, United Arab Emirates, Venezuela, Zimbabwe.Footnote 15

- New constitutions almost always enshrine privacy rights: Iraq’s new constitution includes a right to privacy,Footnote 16 while we are working with groups in Nepal to ensure privacy is included in their new constitution (set to be completed this year).Footnote 17

- Even when a right to privacy is not specifically enumerated or is limited to a single component(e.g. ‘search and seizure’ in the U.S. constitution, or ‘liberty’ in the German constitution) courts around the world are creating a jurisprudence of privacy, often linking the right to privacy with the fundamental ‘dignity and liberty’ constitutional components or finding it implicit in other rights. This has emerged in non-Western countries as diverse as India,Footnote 18 Japan,Footnote 19 and Uruguay.Footnote 20

- There are countries with no specific mention of privacy in their constitutions or in their jurisprudence, including MalaysiaFootnote 21 and Singapore.Footnote 22

Of course the regard for privacy may vary widely, and enforcement may be inconsistent. But privacy rights are not inherently alien to these cultures, or at least not to their political and legal systems.

‘Development’ vs. ‘human rights’ vs. ‘privacy’?

A frequent criticism in the development discourse about ‘human rights’ is that human rights are worthy considerations but they are not high on the list of priorities for the developing world. That is, developing countries must focus their limited resources on building basic infrastructure and providing access to essential services. Developing countries, along this line of reasoning, have much more important things to do than to worry about human rights.

According to the Office of the UN’s High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), development and human rights are interdependent, as they both aim to promote well-being and freedom, based on inherent dignity and equality of all people.

“Human rights and human development share a preoccupation with necessary outcomes for improving people’s lives, but also with better processes. … When human rights go unfulfilled, the responsibilities of different actors must be analysed. This focus on locating accountability for failures within a social system significantly broadens the scope of claims usually associated with human development analysis. In the other direction, human development analysis helps to inform the policy choices necessary for the realization of human rights in particular situations.”Footnote 23

They are often compatible goals, and even interdependent. The OHCHR argues that human rights are essential to good governance and effective government.

Even where we accept that human rights and developing countries are not mutually exclusive, and we have settled concerns of cultural imperialism, there may yet be concerns that privacy itself does not deserve high placement on any policy agendas. Essential to democratic development of any country are functioning democratic and legal systems, effective government administration, and free and open media, amongst other core components. Some may contend that yes, we must protect against torture and detention without trial, and perhaps attend to free expression, and perhaps government transparency and accountability; but privacy is not high on the list of priorities, and may even interfere with these other noble goals.

We must not ignore the times where privacy, human rights, and development agendas may conflict. Whether it is the prevention of the spread of HIV, or the registration of mass populations of refugees, there will be times where the need to collect information on vulnerable groups and people is necessary. But this could be true of any qualified fundamental human right. In turn, the process of qualification would require that accountability and protections be built into these systems to reduce any unnecessary and disproportionate risks.

Indeed, privacy can be incorporated into the accountability structures of development and human rights objectives. Just because people live in developing countries does not mean that they are ignorant of their own needs and desires for privacy. Registration systems established for even the most noble intents can be used to exclude people unfairly, or worse, to identify individuals and/or groups for undue attention. The use of interception and surveillance technologies by oppressive governments during the recent pro-democratic revolutions in Northern Africa and the Middle East demonstrated that regimes that collect information for the national security of a developing country may not always use this power for good.

Privacy is an issue only in advanced economies?

Criticism of privacy as a global human concern focuses on how privacy is a modern concept that only applies in modern contexts. That is, the importance of privacy in developing countries may be limited by the lack of industrialisation. In turn, without development there is no need for privacy. The argument here is that privacy is always technology-dependent and our conceptualisation of many developing countries is that they are well behind on technological development. Privacy matters to the ‘Facebook Generation’ in the West, not to those in sub-Saharan Africa who are struggling to get access to library books. Similarly, laws limiting communications surveillance may be important, but when most people do not have access to computers the risks of abuse are low.

This view of the world does not reflect the current state of affairs. Information and communications technologies are spreading quickly in the developing world. The International Telecommunications Union, a UN agency, estimated that by the end of 2010 the developing world will have accounted for an estimated 45% of global broadband subscriptions. Footnote 24 Mobile phone penetration around the world is still rising, as the ITU estimated that there are over 5.3 billion mobile phone subscriptions, including 940 million 3G subscriptions. In turn, the Facebooks and the Googles are quickly expanding in developing countries,Footnote 25 often building specific interfaces to cater for the reduced quality infrastructures in some parts of the world.Footnote 26

Because of the availability of foreign development funds, governments in the developing world are deploying some of the most advanced technologies, more so than in the developed world in some cases. As the next section will show, advanced uses of health registries, biometrics, genetics, and communications surveillance are spreading across developing countries at rates not even seen in developed countries.

Even if it were true that human rights are not of value in countries where the focus is more on ensuring that people have access to their basic needs, the ultimate aspiration for the developing countries of the world is human progress. Put simply, the purpose of development is for these nations and their peoples to attain the ability to promote well-being and freedom. Both the process of development and the establishment of human rights seek to allow people to determine for themselves the conditions of their lives. Therefore what is once a failed state, we hope, will eventually become a developing country, and then become developed. If the goal is to eventually be developed, where issues like determination over information flows are of some value, then we must question why proponents of development would ignore it at an earlier stage.

One day these countries will have the techniques and technologies, and we share an interest in ensuring that their infrastructures are strong and that rights are built in. After all, why should the communications privacy of an African be any less than that of a North American or European? Considering most of these countries have constitutional values for an analogue world (e.g. inviolability of the ‘home’), it is worth ensuring that it applies to the digital world (e.g. protecting data held in the ‘cloud’.)

Lessons and transborder policy flows

The purpose of the above discussion was not necessarily to promote privacy higher on the policy agenda, but rather to raise issues for consideration prior to presenting the data on policy developments in some developing countries. What we present below is a summary showing that surveillance and privacy issues are rising on policy agendas.

The world is indeed a rich and diverse place. Just because there are some values we may wish were universally held, they are not necessarily so. Varying conceptualisations should not be seen as a problem to be fixed. Rather they may help us better understand our own definitions, preconceptions, and assumptions. It is possible that we may have much to learn from other cultures and contexts as our ‘Western’ values may yet change and come to approximate the values held in other places.

This may be both positive and negative. In recent months researchers and technologists have uncovered surveillance tools used by governments of Northern Africa and the Middle East,Footnote 27 and they have seen how these technologies are not only similar to those found in Western Europe and North America, but originate from Western EuropeFootnote 28 and North America.Footnote 29 Similarly, the technology used by the Iranian government to conduct surveillance of the opposition movement was found to be from Nokia Siemens, designed to European standardsFootnote 30 and in accordance with U.S. policy from the 1990s.Footnote 31 On the other hand, some developing countries may be leading the world in surveillance systems, and we may have much to learn about how these policies play out as they could also inform our future practices.

III. Policy Agendas

In many ways, developing countries are leading the way when it comes to adopting and developing new surveillance practices. Policies rejected in the West are finding traction in the developing world.

In this section we present some examples of policies emerging in developing countries around the world. This is not intended to be a comprehensive statement of all privacy and surveillance policies around the world. Looking at some of these examples we can see some of the policy dynamics at play to better understand the challenges and opportunities that exist for engaging with developing countries.

National identification systems

New national identification systems are springing up across the developing world. The paper-based ID cards of yesteryear are gradually being replaced with systems built on digital technologies, cards and passports with contact and contactless processing technologies, vast databases of personal information, and new ‘biometric’ technologies such as digital photographs, fingerprints, and iris scans. These systems provide governments with the capacity to better identify and manage the citizenry, whilst introducing a sophisticated means of surveillance and social sorting.Footnote 32

The policy drivers for the adoption of these new ID systems are wide-ranging and numerous. Passport systems are being upgraded with biometrics due to requirements imposed by international bodies such as the International Civil Aviation Organization, a UN agency, although these requirements are regularly misunderstood or misrepresented.Footnote 33 Governments are also rushing to embrace new ID systems out of a desire to be seen as being technologically ‘modern’. Recording citizens’ personal details and issuing unique identity numbers are believed to be a part of ‘good governance’ in the 21st century.

Under this notion of good governance, the funding for these ID programs often comes from Western governments or international donors, supported by the know-how of multinational companies. As examples,

- under the direction of Interpol, the Belgian company SEMLEX is developing a new biometric passport for the Economic and Monetary Community of Central African States (CEMAC), which includes Cameroon, Congo, Central African Republic, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea and Chad;Footnote 34

- the governments of LesothoFootnote 35 and PakistanFootnote 36 are receiving funds from the U.S. government to implement identity systems;

- the Swiss company, Trüb, is developing Azerbaijan’s new biometric passport;Footnote 37

- Rwanda’s new electronic ID system is being built by De La Rue,Footnote 38 the funding source for which is unknown;

- the World Bank is funding Bangladesh’s new ID card despite concerns about social exclusion;Footnote 39 and

- the United Nations Development Program is funding Zambia’s new multi-purpose ID scheme.Footnote 40

The funding of these systems can take interesting turns. Pakistan’s National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA) has signed a contract to help Nigeria issue computerized national ID cards.Footnote 41 This is a form of technology transfer with important surveillance and privacy consequences, particularly as Pakistan has had problems with its own identity system.Footnote 42 Meanwhile the Japanese government offered to fully fund Uganda’s national ID system, provided that the Ugandans used Japanese firms’ technologies, and collected detailed information on all Ugandans including criminal histories, banking information, and voter information. The Ugandan government rejected the proposal and selected a German firm instead.Footnote 43

Governments are often keen to be perceived as leaders or innovators. India and Mexico are pursuing unprecedented biometric-based identity schemes for their national populations.

- India’s aim is to issue a unique identification number to all the country’s residents, for the purpose of empowering the poor to ‘bring them into the global economy’. It will involve the collection of fingerprints, iris scans, and digital photographs of each Indian citizen. The system is expected to cost at least $10 billion over the next five years.Footnote 44 In response to claims that other countries, such as the United Kingdom, have moved away from such ideas, the Indian government responds that it has the necessary expertise to make it all work. It is working closely with IT companies to build the technical infrastructure and partnering with institutions such as banks, to serve as registrars for the program. However, critics point out that authorities are already registering citizens even though the program has not been authorised by the Indian Parliament.

- Mexico is aiming to enrol young people in the Government’s new ID system.Footnote 45 It plans to collect the iris scans and fingerprints of 25 million young people by the end of 2012.Footnote 46 The Mexican ID program is being built and managed by the multinational technology firm, Unisys.Footnote 47

In their public discourses, both governments have expressed the desire to be world leaders in these technologies. The challenge is that these are huge projects with new technologies. They both claim that despite the complexity of these systems, they are fully capable of protecting their security and integrity.

These new identity systems are often a means for the state to collect and consolidate vast amounts of personal information on citizens. For example, Indonesia’s new electronic ID card project involves the collection of extensive personal data, including marital status, blood type, parents’ names, employment status, physical or mental disabilities, birth certificates and divorce certificates, place and date of birth, fingerprint biometrics and a photograph.Footnote 48 This information is then shared across government agencies. In Mongolia, the new national identity scheme will be accessible by officials in the electoral commission, tax department, military recruitment office, police, customs, local registrar, and passport office.Footnote 49

National identity systems can also emerge through other government policies, such as voter registration initiatives or through the provision of national healthcare. Bolivia is investing in a biometric voter registration system, which is being built by Smartmatic and NEC.Footnote 50 In Nigeria, the government is in the process of collecting photographs and fingerprints from all voters in an effort to reduce voter fraud. However, doubts remain about whether these technologies are capable of fixing systemic corruption and malfeasance.Footnote 51 Biometrics are also being used for voter registration in the Philippines, where there are over 50 million registered voters.Footnote 52

In other contexts, the use of ID technologies such as biometrics is being imposed on people by foreign militaries intent on singling out dangerous elements. Coalition forces in both Afghanistan and Iraq have been collecting various biometrics from people since the beginning of the military conflict in these countries. However, these technological legacies will remain in place after the forces go home, leaving behind a powerful surveillance capacity.Footnote 53

Surveillance of movement

Governments are increasingly implementing extensive data collection at borders. Foremost among these is the fingerprinting of foreigners entering a country. The U.S. government was the first to introduce mandatory fingerprinting of visitors (a program known as US-VISIT).Footnote 54 Since then developed countries such as Japan and Korea have followed suit. These policies and practices are now being emulated by some developing countries.

- Malaysia will soon implement its National Foreigners Enforcement and Registration System, which will collect fingerprints from all foreigners entering the state and will interface with the Malaysian Immigration System and the country’s Advanced Passenger Screening System;Footnote 55

- Since 2008 Ecuador has been implementing proposals to fingerprint foreigners as they enter the South American state;Footnote 56

- The cost of a Mozambican passport has risen more than ten-fold—to 3,000 meticais or $106— since the introduction of biometrics,Footnote 57 putting it out of the reach of poor citizens and, according to some allegations, forcing some into illegal migration;Footnote 58

- Ghana has announced plans to collect biometrics from all unregistered migrants from neighbouring countries, including Fulani herdsmen;Footnote 59 and

- Qatar recently announced plans to fingerprint all foreigners entering the country, as well as conducting mandatory medical checks.Footnote 60 The Qatari government has also expressed an interest in introducing iris scans at the border,Footnote 61 following the lead of its neighbor in the Gulf, the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The UAE was the first country to implement a large-scale iris biometric system at its border, with all foreigners who hold visas required to undergo iris scans.Footnote 62

Scanners that generate full-body images of passengers were recently introduced in airports in North America and Europe, where there has been considerable controversy and public debate about their effectiveness, appropriateness, and invasiveness. Governments in developing countries such as Nigeria and India are also considering these technologies, despite controversies elsewhere. Nigeria was an early adopter because the ‘underwear bomber’ who triggered the Christmas Day scare was a Nigerian national. There are now allegations of the misuse of these scanners by Nigerian security authorities.Footnote 63 Meanwhile, in India it is unclear whether the government will actually go forward with their plans,Footnote 64 claiming that there are cultural sensitivities to consider.Footnote 65

Governments are also collecting vast amounts of personal information on travellers from airlines and reservation systems. The collection of both advanced passenger information and passenger name records is spreading as firms like the Switzerland-based firm SITA promote the collection and sharing of this information through their IT systems.Footnote 66 Once these data are collected it is more likely that passenger analysis at borders and airport pre-screening will follow.

Communications surveillance

Communications surveillance comes in different shapes and sizes, ranging from real-time interception of communications, to laws for retaining communications-related data, to identity requirements such as Subscriber Identity Module (SIM) card registrationFootnote 67 and cybercafé ID policies.Footnote 68 As we have seen in the case of Iran in 2009 where it was discovered that the government had surveillance capabilities enabled by European firms,Footnote 69 which could then be used to spy on opposition movements, these surveillance trends represent a worrying set of developments, especially in developing countries with state-owned or state-controlled telecommunications companies.

SIM card registration is arguably the most widespread type of communications surveillance practiced in developing countries. These policies require that SIM cards be registered with personal information such as name, ID number, home address, and sometimes biometrics such as fingerprints. The widespread introduction of SIM card registration policies has the potential to spell the end of anonymous communication. However, in many places these registration policies have proven ineffective and, at times, counterproductive. And in certain countries, such as Mexico, they have been fiercely resisted by citizens.Footnote 70

- In Mozambique, where there are more than six million mobile phone users, the government recently passed a new law banning unregistered SIM cards. This policy was introduced following social unrest in the country’s capital, sparked by rising food and water prices. However, there are a limited number of SIM card registration offices, and waiting times are notoriously long;Footnote 71

- Ghana’s attempt at enforcing registration policies resulted in a sharp decline in SIM card sales;Footnote 72

- Nigeria continues to struggle to implement its SIM registration policies effectively, with government and business still in dispute over who should pay for this form of surveillance.Footnote 73

SIM registration policies could in fact be leading to social exclusion by creating insurmountable obstacles to gaining access to communications technologies, where those without fixed addresses and adequate identity documents will not be able to register.

SIM registration policies may even pose a chilling effect. In Mexico, the government’s SIM registration law has been circumvented as cheap ‘pirate’ cards have become available on the black market.Footnote 74 Yet this has not inspired confidence in users of mHealth services, such as those patients using the VidaNet service—a HIV patient-reminder system operating in Mexico City, which is currently facing difficulties providing a privacy-friendly service in a country with a national SIM registration program.Footnote 75

Recent events illustrate the extent and degree of sensitivity around communications interception in various developing countries:

- Legislators in Indonesia want to give the National Intelligence Agency (BIN) the power to conduct wiretaps without judicial oversight. The draft national intelligence bill containing the relevant provisions does not provide specific details about mechanisms for restricting or overseeing the intelligence agency’s interception powers.Footnote 76

- In 2009 researchers uncovered that TOM-Skype users in China were having their chat messages and personal details monitored and retained on insecure, publicly-accessible servers. This surveillance was ostensibly conducted by Chinese government authorities.Footnote 77

- Wiretapping continues to be a controversial and high profile topic in India. In early 2011 it was announced that a single domestic service provider (Reliance Communications, the second largest in India) conducts, on average, 82 telephone intercepts per day.Footnote 78 The same month it was made public that former political leader Amar Singh's telephone had been wiretapped on the direction of police in Delhi.Footnote 79 This revelation followed an uproar in 2006, when the main opposition party accused the government of bugging its leader’s phones.Footnote 80

- In 2010, Research In Motion, the company behind the popular BlackBerry service, announced that a firmware update in the UAE, pushed out to subscribers by the national carrier Etisalat, contained spyware, which was designed to transmit received messages back to a central server.Footnote 81

- Following the disputed presidential elections in Iran in 2009, Nokia Siemens Networks (a joint venture between Nokia and Siemens) came under fire for having provided the Iranian Government with systems to monitor the communications of protestors. Footnote 82

More advanced forms of communications surveillance are on the horizon in developed countries and yet seem to be already deployed in developing countries. Firms who develop Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) technology, which permits the real-time interception and analysis of packets of data passing through the Internet, are now exploring new markets for their “network management” systems after earlier rejections in Europe and North America. Two telecommunications companies in Brazil have already introduced DPI technologies,Footnote 83 and it appears that the Middle East and Asia are next in line to adopt these measures,Footnote 84 though it seems that they have already arrived: Narus, the Boeing-owned company, recently drew negative attention because it had provided DPI technologies to the Egyptian government. Narus claims to also have clients in India, Korea, Japan, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, “and many more” countries.Footnote 85

Electronic health systems

Much like national identity systems, the introduction of eHealth systems is generally perceived as a positive development for governance in poorer parts of the world, with the objective being to improve the delivery of healthcare and make national health systems more efficient. However, these proposals often do not consider the significant privacy and security risks that arise due to the digitization, centralization, and sharing of health-related data.

In many places, the priority is simply to get a functioning health information system up and running as quickly as possible, very often with limited financial, technical and organizational resources. Yet, by ignoring privacy and security concerns new risks are being introduced to already vulnerable patients, potentially leading to increased stigma, social exclusion or persecution (depending on the context).

We recently examined the many complex issues surrounding eHealth privacy and security in depth for the International Development Research Centre. Our reportFootnote 86 scopes the terrain of medical privacy and health information security and suggests ways of reinvigorating privacy in eHealth implementations.

In our research we found an international trend towards bringing disparate health systems together under a single national authority. If these centralization trends continue, they may result in the largest collection of information on a country’s citizenry, and in a way a de facto civilian registry. A national registry of citizen information is certainly useful for governments to understand and manage their populations, but these are usually better established for specific purposes through deliberative processes to ensure they are fit for purpose,Footnote 87 not created as a side-effect of providing healthcare. A population registry could also have many secondary effects that are not well considered while we establish a health registry, as it can, for instance, reveal ethnic origin or religious affiliation in a systematic manner.

In some countries we heard of plans for storing medical information in the ‘cloud’, where information on a citizenry will be stored in another country, and thus another legal jurisdiction. The distributed system and the institutions seeking access may not be governed by the same policies and procedures as a local storage arrangement. If not carefully designed, a single record in one non-state entity could provide the key to gaining access to the entire health record of an individual or even a whole community.

Finally, even as the systems and practices in a developing country are being overhauled, little work was being done to establish new policy frameworks for the protection of privacy and security. Capacity-building in these countries focused mostly on deploying new systems, at great cost.

DNA databases

National DNA databases are quickly spreading globally. These are forensic systems that facilitate criminal investigations, though in many debates they are now perceived to be an essential component of crime prevention.

It is important to understand the criteria determining whose DNA can be sampled and stored, for how long it can be retained, and under what circumstances it may be removed from a database. Yet these essential questions about the policies and systems are too often ignored.

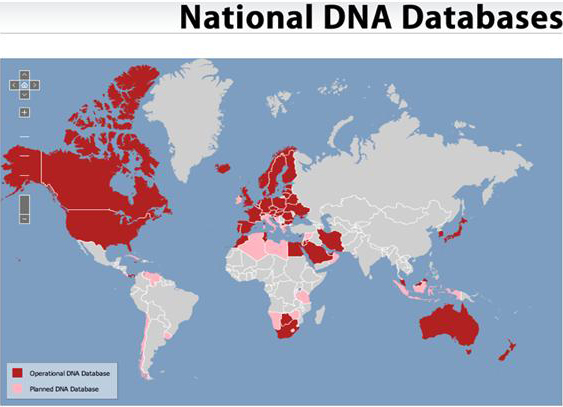

A recent report from the Council for Responsible Genetics (CRG) provides a good overview of the extent of diffusion of DNA databases across the world. These databases are “expanding unchecked at an alarming rate and efforts are underway to harmonize them.”Footnote 88

A number of developing countries have already developed operational DNA databases, including Botswana, China, Colombia, Egypt, FYR Macedonia, Iran, Jamaica, Jordan, Lithuania, Malaysia, Morocco, Panama, Romania, South Africa, Tunisia, and Ukraine. Moreover, the following developing countries have established plans to set up a national DNA database: Albania, Algeria, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Chile, Costa Rica, Cuba, India, Indonesia, Lebanon, Lesotho, Libya, Mauritius, Montenegro, Namibia, Syria, Tanzania, Thailand, Uruguay, Venezuela and Zimbabwe.

Even in jurisdictions where courts have already called for changes to DNA practices, changes are slow in coming. For instance, in 2008 the European Court of Human Rights ruled that strict safeguards must be in place for DNA databases,Footnote 89 and yet by March 2011 the UK had yet to make any changes and other countries within Europe are still lacking adequate protections.

Visual surveillance

The introduction of CCTV has historically been controversial. Though the practice is now spreading quickly in North America and Europe, there has been much debate and research on the effectiveness of these systems. Empirical research on CCTV has found that the crime prevention benefits of video surveillance are uncertain or far less than envisioned.Footnote 90

Despite the mixed outcomes of CCTV implementations, the government of Mexico City recently announced plans to introduce 100,000 new security cameras in the city center. As the project administrator recently stated in an interview: “For its complexity, solidity and the speed with which we are doing it, this project has no rival.”Footnote 91

Research points to China as another place where the market for CCTV is growing dramatically, with tens of thousands of cameras being deployed in some cases.Footnote 92 Industry sources have expressed their hopes that India will be the next growth market for video surveillance systems.Footnote 93

Surveillance systems for emergency management

When disasters strike, governments introduce measures to assist in helping those who were affected, for example in aid or food distribution. These systems very often include an information-gathering component. In these contexts, concerns about the privacy impact of these measures are usually not properly debated and deliberated.

The ‘Watan’ card, introduced in Pakistan following the floods there in 2010, is a case in point. It was intended as a means to facilitate the distribution of cash and aid to affected families. The cards were issued by NADRA, Pakistan’s identification authority, with the involvement of the Asian Development Bank, World Bank, and UNHCR.Footnote 94 One of the problems with the system, however, was that it required that aid recipients prove their identity (using previously state-issued NADRA ID numbers) before they could claim a Watan card. In many cases, such identity documents had been lost or destroyed in the floods. As a result of these stringent identification policies, tens of thousands of people were denied aid after the flooding.Footnote 95 Following international public outcry, these ID requirements were relaxed.

Similarly, UNHCR has been developing registration systems for refugees around the world, some of which include the collection of biometrics. This registration information is essential for the protection of the refugee, as once the refugee’s information is collected that refugee is then protected under refugee conventions, and is afforded rights and access to services. Therefore it is essential that this information is stored by UNHCR. However, the security of these systems is challenging partly due to the complex environments within which UNHCR staff operate; they often work with other implementing partners who are seeking access to refugee information, including host governments. This has led to much review of UNHCR’s security and privacy practices.

Emerging laws on privacy protection

The landscape of privacy and surveillance policy in developing countries is not necessarily all bleak. There are frequent calls for new laws to protect privacy. There are many new and pending laws. Data protection regimes are spreading, though clearly much work is still required as there are large gaps.

Previously, governments outside of Europe introduced data protection legislation in order to enhance trade opportunities for their outsourcing industries. This is still the case, but now many of these emerging laws also provide protection for citizens of these countries. In the Philippines, a draft law was introduced in order to enable the transfer of information from Europe for outsourcing services and to also regulate the processing of information held by the government.Footnote 96 In India, the current momentum behind a national data protection laws is not only for outsourcingFootnote 97 but also in order to create a regime of safeguards around the proposed identity system.Footnote 98 Bangladesh and Pakistan are also considering laws because of outsourcing, but also because of previous abuses.

Meanwhile regional activity is leading to the spread of new data protection laws. APEC has been assisting the development of laws in the Asian Pacific. Meanwhile the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has recently concluded a relatively strong data protection law, that re-affirms the human right to privacy, for the purpose of harmonising legal systems, and responding to ‘technology such as the Internet, with its facilities of profiling and tracing individuals’, and ‘the increasing use of information and communications technologies may be prejudicial to the private and professional life of users’.Footnote 99

Importantly, courts are increasingly recognising the importance of privacy and are now elaborating on constitutional rights. In Pakistan, where there is a constitutional protection of privacy under article 14 on dignity and privacy, the Supreme Court has been developing jurisprudence. In 1996, in a case that uncovered the wide-spread communications surveillance of judges, politicians, and military and government officials, the Supreme Court ruled in Benazir Bhutto vs Federation of Pakistan that the practice was unlawful and required authorisation by judges of the Supreme Court. In 2004, the Lahore High Court ruled in favour of financial privacy in the case M.D. Tahir vs Director, State Bank of Pakistan, concluding that it was illegal to collect ID numbers and other information of bank account holders without any allegation of wrongdoing.

Since the 1960s, the Indian Supreme Court has been developing a body of jurisprudence on the right to privacy as part of the Article 21 Fundamental Right to protection of life and liberty.Footnote 100 In Kharak Singh v. State of UP from 1963, the Supreme Court required the government to limit home searches, borrowing from British jurisprudence the importance of the home as a private space. In Gobind v. State of M.P. in 1975 the court ruled again on home searches, stating that the dignity of the individual is at stake, and thus privacy can only be denied when there is a superior and important countervailing interest. The protection of privacy of communications was established as a constitutional right in People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) v. Union of India 1997, requiring that the right to privacy only be curtailed where there is a procedure established by law, incorporating European judicial approaches. Other cases include media privacy (State v. Charulata Joshi 1999), the protection of personality (R. Rajagopal v. State of Tamil Nadu 1995), and protecting medical information (Mr. ‘X’ v. Hospital ‘Z’ 1998).

A more recent case that is particularly relevant to this report was decided in July 2009 when the Indian High Court in Mumbai issued its opinion in the case of whether it should overrule the ban on homosexual intercourse. The Court reviewed Indian jurisprudence on the right to privacy and reviewed foreign case law, including cases from the U.S. and Europe to conclude that banning homosexual intercourse was an unjust interference with privacy. The Court then held that:

“it is not within the constitutional competence of the State to invade the privacy of citizens lives or regulate conduct to which the citizen alone is concerned solely on the basis of public morals. The criminalisation of private sexual relations between consenting adults absent any evidence of serious harm deems the provision's objective both arbitrary and unreasonable. The state interest “must be legitimate and relevant” for the legislation to be non-arbitrary and must be proportionate towards achieving the state interest. If the objective is irrational, unjust and unfair, necessarily classification will have to be held as unreasonable. The nature of the provision of Section 377 IPC and its purpose is to criminalise private conduct of consenting adults which causes no harm to anyone else. It has no other purpose than to criminalise conduct which fails to conform with the moral or religious views of a section of society. The discrimination severely affects the rights and interests of homosexuals and deeply impairs their dignity.”Footnote 101

Importantly, the Government argued that the culture of India was such that homosexuality was immoral, even though the law that banned homosexuality was actually based on an old British law.

While there are more and more cases emerging around the world, these still require vast amounts of time and resources to bring these cases to courts. Additionally, as we see in the West as well, even when a law or a practice is ruled unconstitutional it takes much political will to see an effective change of law, and often requires functioning regulatory systems and checks and balances to ensure against future abuses. Just because courts around the world have ruled that communications surveillance must be tightly regulated, this does not mean that illegal surveillance doesn’t take place. In fact, the challenge of regulation is something that perhaps unites both the developed and developing countries of the world.

IV. Developing Opportunities

In countries around the world, almost without regard for cultural variations or economic differences, surveillance is rising on the policy agendas. New systems are being deployed to collect information on large populations without adequate technological and policy safeguards. The technologies being deployed are often untested, and may give rise to secondary effects such as social exclusion or discrimination. Though legal safeguards exist in the form of constitutional safeguards, and sometimes even in the form of data protection laws, we may rely too greatly on weakened legal and judicial institutions. Too often, the legal safeguards are inadequate or poorly resourced. This is no less true when the purposes of the systems are beneficent: while we build citizen registries or health systems for the good of a nation, we often fail to uphold our good intentions through developing adequate policy frameworks and other safeguards.

Worryingly, countries around the world are just as eager to lead on new surveillance practices as they were once eager to lead on ‘e-commerce’, or ‘e-government’. They are implementing systems that we have not yet even considered within our own countries, or sometimes we have considered and rejected.

This does not necessarily mean that there will be a global divide. The rate of technological development of advanced techniques of identification and communications surveillance, as instances, may lead to cost reductions due to innovations in the marketplace through sales in developing countries. Put simply, these technologies are being tested in developing countries and may yet come to the developed world.

With billions being spent in developing countries on these technologies, it is likely that they will be reintroduced in Europe and North America. After all, if the West and international development organisations are funding surveillance of Africans and Asians, why should these systems not also be applied against Westerners? The national security and crime-fighting concerns in the developed world are increasingly similar to those in the developing world, and vice versa.

There is some cause for optimism. In recent years, there has also been a noticeable rise in calls for greater protections and safeguards. Because of noted and publicly disclosed surveillance abuses, countries are now considering new laws. In other cases, because of the introduction of new surveillance systems, governments are considering counter-balancing them with legal protections.

Opposition voices and the emerging voices of civil society organisations are calling for protections, protesting against developments, conducting research to question the effectiveness of policy decisions, and seeking alternatives. They are also borrowing some of our legal ideas and using them to come up with their own. We may do the same: we can look to the Indian High Court decisions and ask ourselves why we do not question unfair practices based on conceptions of morality; or learn from the Egyptians and Tunisians as they discover the systems of surveillance that were put in place to silence their calls for change.

These debates and deliberations in developing countries are still in their nascent stages. This is also true in many countries in the West, as they also lack the legal, political, social, and economic infrastructures for democratic deliberation. They all need support.

Canada can play a key support role. Canada’s International Development Research Centre has led the world with unprecedented levels of support for capacity building on privacy in developing countries. The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC) is actively involved internationally in privacy promotion and protection initiatives, with the goal to promote internationally the right to privacy, in particular within countries that do not have comprehensive privacy legislation. This is done primarily through participation in groups such as APEC, the Ibero-American Forum of Data Protection Authorities and the Francophone International Data Protection Authorities Association. The OPC also regularly hosts foreign delegations looking to put in place new privacy regimes. Given its diversity of legal systems and languages, the OPC could do even more to make its knowledge accessible and relevant to more countries. The OPC and its advisors can run training sessions for lawyers and judiciaries around the world to explain the legal cases and Canada’s story on human rights and freedom. The OPC could work with civil society organisations to build capacity on the importance of privacy in the conduct of government and commerce. When regulatory systems are established, the OPC and the international regulatory community could help new regulators to understand the challenges of enforcement, the value of effective educational programs, and the benefits of working with other institutions.

We must all set good examples. It is very helpful to state that the UK Government has abandoned its biometric identity card, for instance, as it may cause some countries to reconsider their own plans. We need to show the benefits of our legal and political structures that have helped make better decisions. We also need to show that we are making the right decisions because otherwise we have weakened any chances for developing countries to question the validity of a surveillance system if it is already widespread elsewhere. Similarly, we must continue to promote best practices amongst technology developers and when necessary regulate industry, as these methods will help ensure that the privacy safeguards built into technologies and services used in Canada are also deployed in Cameroon.

Even with all the good examples and all the leadership, surveillance systems will continue to expand in developing countries so long as international organisations and governments fund their deployment. We must call on these donors, foundations, and agencies to consider privacy and human rights in their development strategies. We must also monitor the international trade in surveillance technologies. Failing to do so may result in a new form of inequality between the developing countries with extensive surveillance, and the developed world without. More worrying is the most negative outcome, where these funds will ensure the continued rise of surveillance industries and services that will eventually become global.

In the meantime, more international research and policy engagement is essential to understanding the extent of these challenges. As we learn more about the risks of information abuse, whether through innocent security failures or invasive security practices, we will hopefully soon find ways to seek solutions to our shared risks.

- Date modified: