Drug testing and privacy

This page has been archived on the Web

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Report prepared by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

INTRODUCTION

"When the current spasm of anxiety about drugs has run its course, we will be left with an array of bureaucracies and technologies that will find other justifications for their continued existence, with serious and long-lasting implications for freedom and privacy… The history of technology is the history of the invention of hammers and the subsequent search for heads to bang with them."Footnote 1

"Between lie detector tests and drug tests, you wonder how anybody can get any work done."Footnote 2

"There has to be some consideration for individual rights. We can't be running around testing anybody at any time."Footnote 3

During the 1980's a confusion of forces pushed drug testing to the forefront of workplace issues. The globalization of the world's economy put ever increasing pressure on employers to reduce their costs of doing business and fuelled their search for the "perfect" employee. Rising levels of drug-related urban crime intensified the "war on drugs", particularly in the United States, a "war" whose focus shifted somewhat from attacking supply to attacking demand. Public safety seemed to be increasingly at risk as the spectre of on-the-job impairment—particularly in the transportation sector—was raised. Finally, as the decade came to a close, the Ben Johnson affair raised new concerns about drugs. Amidst all this emerged the attitude that testing of "everyone but me" was the solution to these ills.

We have used the term "confusion of forces" because quite different problems gave rise to them. In some cases it was illegal drug use, in some it was performance impairment and, with athletes, it was performance enhancement. Curiously, workplace drug testing through urinalysis seemed to offer the quickest fix to many of these problems. Curious, because urinalysis cannot measure impairment. Yet, apart from the desire to attack the demand side of the illegal drug trade, almost all forces calling for testing stem from concerns about on-the-job performance impairment. Curious, too, because drug testing is extremely intrusive of one of our most fundamental rights—the right to privacy. It is especially intrusive when imposed randomly, without "reasonable suspicion" safeguards, as many testing proponents advocate.

To understand just how intrusive drug testing is, a brief discussion of the mechanism of drug testing may be helpful. It is found in Part I.

The prevailing testing method of choice is urinalysis. One person’s account of urinalysis illustrates graphically just how degrading the experience might be:

"I was not informed of the test until I was walking down the hall towards the bathroom with the attendant. I thought no problem. I have had urine tests before and I do not take any type of drugs besides occasional aspirin. I was led into a very small room with a toilet, sink and a desk. I was given a container in which to urinate by the attendant. I waited for her to tum her back before pulling down my pants, but she told me she had to watch everything I did. I pulled down my pants, put the container in place—as she bent down to watch—gave her a sample and even then she did not look away. I had to use the toilet paper as she watched and then pulled up my pants. This may sound vulgar—and that is exactly what it is. . . . I am a forty year old mother of three and nothing I have ever done in my life equals or deserves the humiliation, degradation and mortification I felt."Footnote 4

Not only is the testing method intrusive. Testing results in the collection of highly sensitive personal information. It tells whether a person may have consumed the drug or drugs being tested for during the recent (and even not-so-recent) past. Related tests on urine collected to identify drug use through urinalysis may identify medical conditions, such as epilepsy or pregnancy, formerly known only (or even unknown) to the person being tested.

Test subjects could be required to disclose use of other legitimate drugs (prescription drugs and over-the-counter inhalants, for example) that could, themselves, cause a positive result. Subjects could also have to disclose certain eating habits, such as the consumption of poppy seeds.

Despite its intrusiveness, urinalysis has been embraced with enthusiasm by private firms and governments alike in the United States. A 1987 survey reported that 58 per cent of the largest U.S. employers then had drug testing programs. In 1986, Ronald Reagan issued an executive order entitled "Drug-free Federal Workplace". It requires the head of each executive agency to establish a drug testing program to detect illegal drug use by federal employees in sensitive positions. The executive order also authorizes testing for anyone applying to work in an executive agency. The U.S. Department of Transport has issued regulations requiring drug testing for transportation workers. As discussed later, this has direct implications for Canadian drug testing policy in the transportation sector.

The private sector in Canada appears equally enthusiastic about workplace urinalysis. A recently-reported Arthur Anderson and Co. survey stated that 48 per cent of Canadian small business executives favour drug testing for their employees. However, reliable numbers are not available on the number of Canadian firms which have actually adopted drug testing programs.

The government of Canada, while initially showing great restraint in the face of drug testing pressures, now appears willing to embrace the process in a range of situations. Urinalysis programs involving inmates, parolees, members of the Canadian Forces and (indirectly) athletes have been in operation for varying periods. Is the announcement in March of two new and broad-ranging testing programs by Transport Canada and the Department of National Defence a signal of the intention of the government to expand urinalysis programs dramatically? This document argues that many elements of these present and expanded drug testing programs can be characterized as unnecessary "overkill".

The growing pressures in society and government for drug testing programs and the intrusiveness of both testing procedures and their results on personal privacy led the Privacy Commissioner to undertake a review of federal government drug testing policy and practice.

While there is no doubt that drug testing infringes personal privacy in a profound sense, one must not be blind to the need to protect the public interest. R.I.D.E. programs, for example, are seen as justifiable intrusions on private rights to safeguard the public good, even in light of the Charter of Rights.

The recommendations contained in this report are offered as a contribution to the ongoing debate and a guide to government. The development of drug testing policies and practices which respect the requirements of the Privacy Act and which keep in appropriate balance public and private rights will be a unique and difficult challenge.

Seeking to find an appropriate balance, one might bear in mind a chilling comment eloquently stated by the editor of Harper's Magazine in a recent essay entitled: "A Political Opiate". Lewis Lapham analyzes a preoccupation with the problem of drugs in society as follows:

"But the war on drugs also serves the interests of the state, which, under the pretext of rescuing people from incalculable peril, claims for itself enormously enhanced powers of repression and control.

For the sake of a vindictive policeman's dream of a quiet and orderly heaven, the country risks losing its constitutional right to its soul."Footnote 5

Widespread drug testing is enormously attractive as a simple, quick fix to a complex social problem. Are the really tough issues—workplace stress, ignorance, inadequate employee counselling and the continuing failure to treat substance abuse as a health problem rather than a social deviance—so threatening that we must pursue a course which undermines many of our hard-won fundamental liberties?

Few would accept a "war on drugs" strategy which permitted employers or the state to intrude into our homes without reasonable suspicion, no matter how helpful such intrusions might be in addressing the drug problem. Yet governments, apparently with some public support, find drug testing so attractive that they propose to authorize intrusions into our bodies.

The burden of proof now rests on the shoulders of government to demonstrate that, in authorizing such intrusions, our "constitutional soul" has not been sacrificed.

PART I: VARIABLES IN THE DRUG TESTING PROCESS

Drug testing can take many forms and involve many variables, among them the following:

- the justifications for testing: for example, personal or public safety, reducing the demand for illegal drugs, enhancing employee productivity, reducing the likelihood of employee theft to support drug habits;

- what types of drugs are being tested for and the "threshold" concentration of each drug that will lead to calling a test result positive;

- who should be tested: job applicants, employees, workers in industries regulated by government, athletes, members of the public applying for benefits, and in what circumstances: pre-employment, post-accident, with cause to suspect impairment, without cause, at random, or some combination of these;

- the testing method: blood, urine, hair, saliva, psychological, breath, and the variety of testing protocols that may be used under each category;

- what testing seeks to identify: present use, present use and present impairment, past use, or past use and past impairment; and

- the intended uses of the test results: dismissal, treatment, discipline, prosecution, refusal of benefits, denial of eligibility to participate in sporting events.

An informed understanding of the scientific limitations of the testing method and a careful delineation of the precise goals of the testing program are prerequisites to any decision as to the effectiveness of a drug testing program. Legal considerations—including the Privacy Act, the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Charter—must also be incorporated into the analysis.

For example, a testing program that does not confirm positive results from screening tests will be unacceptable because it generates many false positives. Urinalysis to confirm impairment would not be useful, even with the proper confirmatory tests, since urinalysis can show past use only. It cannot show either present use or present or past impairment. Finally, even a properly designed test intended to confirm drug use may nonetheless be unacceptable because of Charter guarantees of “liberty” and protections against unreasonable search and seizure.

In what follows, several variables that may be involved in drug testing are explored in greater detail.

a) The Justifications for Testing

Proponents of drug testing advance any of several justifications.Footnote 6 Some are more relevant to certain environments (the workplace, for example) than others. Much of the following material describing the justifications for testing is based on an analysis of American literature and surveys, given the limited Canadian material and surveys on the subject.

(i) Reducing the demand for illicit drugs

Testing reflects society's concern about the "pervasive" use of illicit drugs and reduces the demand for them. This is clearly an important, if not the most important, justification behind President Reagan's 1986 executive order.Footnote 7

The executive order calls for a drug free federal workplace in the United States and focusses on illegal drugs.

The threat of a drug test which might jeopardize one's livelihood may deter a person from using illegal drugs. Thus, it is argued, drug testing can reduce the demand for illicit drugsFootnote 8 and complement attempts to reduce the supply of drugs. Drug testing programs aimed at reducing demand would focus only on illicit drugs—those that are banned outright or that have been obtained through illegal acts (such as the doctoring of prescriptions).

Private employers may argue that, by testing for illicit drugs, they too are doing what they can to reduce the demand for illicit drugs. One recent American survey suggests that 10 per cent of one sample group of large American corporations with testing programs justified them as a means to curb illegal drug traffic.Footnote 9 However, enhancing workplace performance (through reducing accidents, protecting a safe work record and improving productivity), appears more often to be the goal of private sector testing.Footnote 10

Almost any group—government, sporting or business—could rely on the justification of reducing drug demand for testing. That justification could in fact support testing an entire population.

(ii) Health and safety

Protecting health and promoting safety are often put forth as objectives of testing programs. These objectives have four aspects:

- protecting the safety of persons being tested when these persons might be injured through impairment (examples might include impaired driving or operating machinery in a factory).Footnote 11 Testing drivers for blood alcohol under the Criminal Code is perhaps the best known example of drug testing premised (in part) on this objective;

- protecting the safety of co-workers by detecting an impaired worker who might cause injury or death. Mine workers, nuclear industry workers, military personnel, police officers, firefighters, train and aircraft crews are examples of those who could be endangered by impaired colleagues;

- protecting the public safety by detecting impairment, or risk of impairment, in anyone whose impairment could harm the public—for example, a truck driver, pilot, train engineer or person operating a nuclear facility. Testing to detect blood alcohol levels is often justified using the public safety argument. Similarly, parole authorities might justify drug testing as a condition of parole by arguing that it will enhance safety in the parolee's community by reducing the risk of the parolee committing aggressive, anti-social acts while under the influence of drugs or to obtain money for drugs. This justification has been identified as the rationale for the government of Canada's consideration of testing;

- protecting the health of the person being tested in the short run, long run, or both. Test results could signal the need to help the person who tested positive. The use of certain drugs (nicotine, alcohol, cocaine, for example) can cause health problems—some minor, and some grave.

The health and safety justification can be used to justify workplace testing and testing wholly apart from workplace considerations. This type of testing program would not distinguish between licit and illicit drugs.

(iii) Efficiency, economy and honesty

Drug testing may be justified as a technique to develop more productive workers, reduce health care costs, verify employee honesty and reduce liability for damage caused by impaired workers.

- promoting efficiency. Employees who are not impaired by drugs (or, indeed, by other factors, such as lack of sleep) will be more productive. They will also be less likely to damage the employer's property. To be consistent, a testing program derived from this justification would not distinguish between licit and illicit drugs. It would focus on any drug that caused or might cause impairment.

- reducing health care costs. A reduction in drug use, both licit and illicit, may result in lower health care costs. Both government and the private sector might rely on this justification for testing.

- verifying honesty. Persons who possess and use illicit drugs are breaking the law. If they break the law in this manner, they might be willing to do so in other circumstances (for example, by defrauding their employers or government agencies which provide benefits). As well, the high cost of illicit drugs may force some persons to commit crimes, including work-related crimes.

Testing may also be used to ensure the integrity of those in drug law enforcement (police, customs officers, prosecutors, judges). Those whose duties involve suppressing the trade in illicit drugs should be beyond any suspicion that they are improperly implicated in the trade. Their involvement in any way could compromise drug law enforcement and the safety of colleagues.

Testing to verify honesty would generally lead to tests for illegal drugs only. Testing to improve the integrity of sports and to ensure that athletes have no unfair competitive advantage, however, could focus on any banned substance, legal or illegal, that enhances performance. - avoiding liability for employees who may injure or kill others while impaired. In the United States, the concept of "negligent hiring" has persuaded some employers to test. Employers who hire (or continue to employ) a person who uses drugs may fear liability if the person becomes impaired and causes harm while on the job.

(iv) Harmonization with requirements established by other countries

In the Canadian context, this justification for testing is especially important. The United States government and private sector have both strongly advocated testing for illicit drug use. American policy reaches into Canada through American transportation regulations and the imposition by American parent companies of testing programs on their Canadian subsidiaries. Canadian owned and domiciled companies could decide to test their own employees to retain access to the U.S. market. The Canadian testing programs that may flow from these political and economic realities will be shaped in part by the nature of the testing programs in the United States. The drugs attacked by the United States Department of Transport regulations, for example, are those, we now know, for which Canada feels the pressure to test.Footnote 12

Similarly, pressures from international sports bodies—the International Olympic Committee and international sports federations—will shape Canadian athlete testing policies.

(v) Comment

Most drug testing programs are based on a hybrid justification. An employer's desire to have productive employees and at the same time to discourage illegal activity may both be used to justify one program. Vetting employee honesty and reducing unsafe work practices may be used to justify another.

President Reagan's 1986 executive orderFootnote 13 offered several justifications for testing for the use of illegal drugs: to prevent lost productivity, to prevent the funding of organized crime through the drug trade, to promote public trust in federal employees, to increase reliability and good judgment and to prevent irresponsible behaviour which could pose a threat to national security.

The drug testing strategies announced in March, 1990 by Transport Canada and the Department of National Defence justify testing as a means to enhance safety, both public and "on-the-job". The Department of National Defence strategy also relies on other justifications—operational effectiveness and a substance abuse-free Canadian Forces among them. There is continuing debate, however, about the extent to which testing programs can contribute to accomplishing the goals identified above.

b) Which Drugs to Test for

The drugs being tested for will vary with—the purpose of the test and with the bias of those calling for testing. If, for example, an organization wanted to identify drug use which could result in impairment, it should test for legal drugs (alcohol and over-the-counter drugs), prescription drugs and illegal drugs that can cause impairment. If it wished only to identify illicit drug use, it obviously need not test for legal drugs.

The testing program instituted under President Reagan's executive order focusses on the use of illegal drugs only. It appears only peripherally interested in impairment by illegal drugs. It does not address testing for the use of or impairment by legal drugs (such as alcohol). The executive order calls for testing for illegal drugs as defined in Schedule I or II of the Controlled Substances Act (CSA). Hundreds of drugs are included in those schedules.Footnote 14

At a minimum, tests must search for cocaine and marijuana.

The Department of National Defence and Transport Canada testing policies, however, are not limited to testing for illegal drugs. They include testing for alcohol. The Transport Canada policy also addresses the use of other legal drugs, for example, over-the-counter and prescription drugs which may impair.

After deciding what drugs to test for, those testing must decide the level of concentration of the metabolized by-products ("metabolites") of a drug in a person's urine that will lead to a "positive" test result. There is general agreement that a certain concentration of a substance—a metabolite of cocaine, for example—must be found before a test is declared ''positive". Threshold levels must be set for each drug.

c) Who Should be Tested and in What Circumstances

Any organization contemplating testing must consider who to test and what circumstances should trigger testing. An employer may want to test an employee after he or she is involved in an accident. Another employer might test simply on suspicion of drug use. Still another might test only where an employee has been involved in an accident and where drug use and impairment are suspected as a cause of the accident. Employers must decide whether to test all employees, senior management, unionized employees, employees whose duties could affect safety, or some combination of these. When coupled with the range of drugs that can be tested for, this creates an enormous and complex array of testing options.

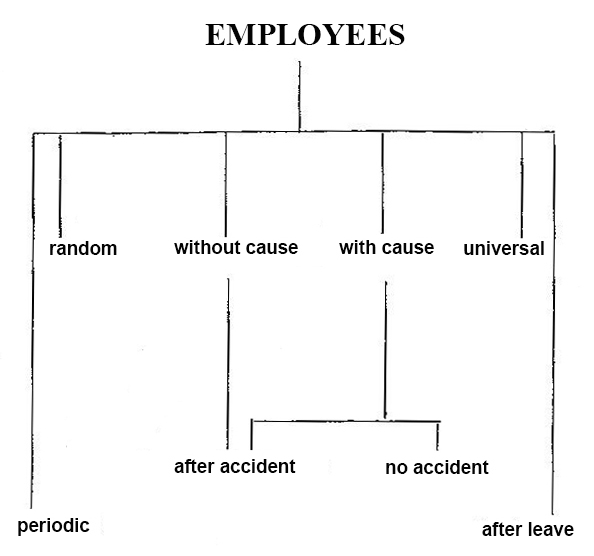

(i) Employees and job applicants

Testing programs for employees and job applicants could take any of the following forms:

Note: The definition of "with cause" could be designed to include any of the following situations:

- with (reasonable) cause to suspect (or believe) drug use on the job or at any time;

- with (reasonable) cause to suspect (or believe) drug use on the job or at any time and resulting impairment;

- with (reasonable) cause to suspect (or believe) drug use on the job or at any time and impairment that may cause or contribute to an accident or incident or that may have caused or contributed to an accident or incident.

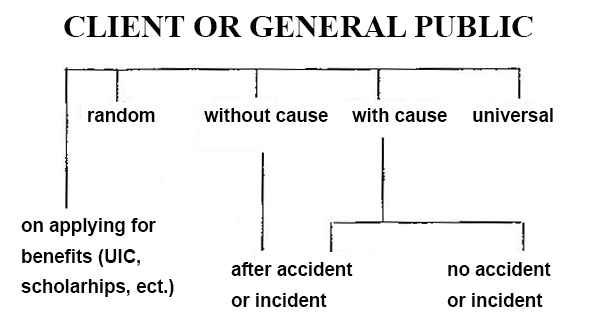

(ii) Clients of government and the general public

Testing programs for government clients (parolees or inmates, for example) or members of the general public (public assistance applicants, students on scholarship, athletes) might take any of the following forms:

d) The Testing Method

Added to the range of options listed above are several relating to the mechanics of testing. Among the types of drug tests now available or contemplated are urinalysis, breathalyzer, blood, hair and psychological profile.

(i) Urinalysis

In Canada the most commonly used test for drugs other than alcohol is urinalysis. Subjects are required to give a urine sample. The test seeks to locate in the urine the drug or metabolites of the drug being tested for. Apart from breathalyzer and blood testing for blood alcohol levels, urinalysis appears to be the sole drug testing method used by the federal government. Several federal institutions, including Correctional Service Canada, the National Parole Board and Department of National Defence, currently use urinalysis. Urinalysis will also be a key component of the testing strategies announced by Transport Canada and the Department of National Defence. All these programs are explained in Appendix A.

Urinalysis itself, however, does not consist of a single, well-defined process. It may involve any of several different "screening" and "confirmatory" tests. The type of drug being sought will often determine which method of urinalysis is to be used. Some are better at identifying certain drugs than others. Other factors affecting the testing method are the relative costs of various methods of urinalysis and the degree of expertise needed to conduct a given test procedure.

(ii) Other forms of drug testing

The Criminal Code breathalyzer test detects the presence and concentration of alcohol in the breath, which can be correlated with blood alcohol levels. A level of impairment is legislatively presumed from this information. When a breath sample cannot be obtained, the Code sometimes permits taking a blood sample. Breathalyzer testing cannot identify the use of or impairment by other drugs.

Some proponents of testing have explored psychological testing to determine the propensity to use illicit drugs. This method, however, fares poorly as a device to identify present or future drug users.Footnote 15

Another test analyses hair strands. Like the rings on a tree, strands of hair can record past events—in this case, drug use. A five-centimeter strand of hair might allow the tester to identify what drugs its owner had ingested over the last three months. This test, however, could not detect recent use (within the last three to five days). Still, it could be combined with other tests (urinalysis, for example) to develop a complete picture of drug use in the immediate and more distant past.

Hair analysis has not yet been shown to be a viable means of identifying past drug use. Even so, it has the potential to become a valid testing procedure. In one sense, obtaining a hair strand is less intrusive than getting a urine sample; a strand can simply be snipped from a person's head. In another sense, it may be much more intrusive, allowing the tester to probe much deeper into the subject's past.

This paper does not deal with the mechanics of all possible forms of drug testing. For example, it does not discuss saliva testing. Instead, it concentrates on the .method most widely used or considered for use today—urinalysis. Much of the analysis contained here, however, could apply to other testing methods.

e) What Testing Seeks to Identify

(i) Distinguishing among past and present impairment, and past and present use of a drug

Urinalysis can indicate only that a person has consumed a drug within the recent past (how far into the recent past will vary according to the drug being tested for). It cannot tell whether a person who has been tested is now using the drug.

At best, a person who tests "positive" for drug use may have been impaired at some past time. One cannot, however, confirm that the person was impaired. Nor can a positive urinalysis confirm that a person was impaired when the test was taken.

Urinalysis cannot determine precisely when the drug was used, (although it can generally tell that it has been used within the last few days).Footnote 16 Nor can it identify the quantity of the drug ingested.

To summarize:

- urinalysis can detect past use of a drug;

- urinalysis cannot confirm present impairment;

- urinalysis cannot confirm past impairment;

- urinalysis cannot confirm present use; and

- urinalysis cannot determine the quantity of the drug consumed.

Accordingly, the limited information provided by urinalysis is in fact of little use in many situations where employers and others are anxious to test. At best, testing may deter drug use, but this effect has not been conclusively shown.Footnote 17

(ii) The meaning of a positive urinalysis result

A positive test result means that the test has detected the drug or a metabolite of the drug being tested for. There may be any of several explanations for the positive result. It may mean that the person being tested:

- is a chronic user of the drug;

- has used the drug intermittently;

- is addicted to the drug;

- is under the influence of the drug; or

- is taking the drug under a physician's order.

False positives do occur, most often after screening tests, and to a much lesser extent after confirmatory testing. Some licit substances (poppy seeds, some asthma inhalants, for example) may produce positive test results.Footnote 18

Urinalysis technology, if administered properly (screening tests coupled with appropriate confirmatory testing and the elimination of other possible substances that may cause a false positive), is acceptably accurate. Human error, however, may cause unacceptable levels of false results.Footnote 19

(iii) The meaning of a negative urinalysis result

A negative test result may mean that the person who has been tested:

- is not using the drug being tested for;

- has taken the drug to be detected by the test but is not taking a large enough dose for it to be detected;

- is not taking the drug frequently enough for it to be detected;

- the sample was collected too long after the use of the drug; any drug metabolites have passed already through the person's system, or

- the sample has been diluted or tampered with.

f) Intended Uses of Test Results

Test results can be used for a range of purposes. Employers testing job applicants might refuse to hire those who test positive (although federal and provincial human rights codes may prohibit this). Current employees may be dismissed, denied promotion, ordered to undertake treatment or relieved of certain job duties. A positive test result may interest investigative bodies which perform security clearances for federal government agencies. A positive test result may prevent a person from obtaining positions of trust in the future.Footnote 20

Outside the workplace, the uses made of results may be equally varied. Athletes who test positive may lose their funding, be stripped of awards or records and banned from competition. Parolees who test positive may see their parole revoked. Inmates who test positive may face discipline.

We are aware of no cases where positive test results have been reported to law enforcement authorities (except for breathalyzer or blood tests administered by or through the police). In any event, criminal charges would not result simply from a positive urinalysis. Existing criminal law does not punish the simple use of a drug.Footnote 21 It focusses instead on possession, manufacturing and trafficking, none of which can be proved in law by a positive test result.

PART II: DRUG TESTING AND GENERAL PRIVACY ISSUES

a) Introduction

Part I outlined several justifications for drug testing and discussed the variables involved in the process. Part II addresses privacy issues arising from drug testing. It argues that drug testing is intrusive and should be strictly circumscribed. Privacy considerations, however, are not the only arguments favouring limits on drug testing. Several general arguments (some interwoven with privacy arguments) are also set out here.

b) The Objections to Drug Testing

Among the arguments advanced against testing are the following:

- the inability of most current tests to measure present or past impairment or detect current use. Most drug tests, including urinalysis and hair analysis, can measure only the past use of a drug. They cannot measure past or present impairment or present use. As one research paper states, there is virtual unanimity in literature that urinalysis cannot be used to make accurate inferences about the extent of impairment at the time a drug is consumed. Nor can urinalysis give rise to an inference of the "hangover" effects of drug consumption.Footnote 22 Thus is the value of the test severely limited. In short, a highly intrusive process—urinalysis—produces little useful information.

Some argue that if "supervisors supervised and managers managed", there would be almost no need for drug tests. As one organization has argued:

“How can an employer identify such an individual [one impaired by drugs or alcohol]? By having an awareness of the signs of alcohol or other drug impairment and by using that awareness in performance monitoring… . The supervisor's awareness, coupled with active monitoring and documentation allow for early identification.

This method of identifying alcohol/drug troubled individuals is known as the performance model. Its focus is limited to productivity and safety in the workplace; it does not deal with the issue of use away from work unless that use affects the job. The value of the model is that it allows management to intervene on the basis of legitimate performance expectations and to maintain union support in doing so.”Footnote 23 - incomplete coverage and the need for repeat testing. Urinalysis, for example, can identify cocaine, benzodiazepine (tranquiliz.er) or amphetamine (stimulant) use within the preceding few days only. A person may have used drugs a week before a test, but would still test negative. Hence, urinalysis could identify only some of those who may have used drugs within the relatively recent past. It cannot therefore be used to make definitive statements about the person's long term drug-free status (hair analysis can assess drug use over a longer period, but is not yet acceptably accurate).

To be even reasonably sure of continuing drug-free status among employees or clients, frequent re-testing would be needed. This would compound both the number of intrusions and the expense of the process.

Repeat testing may encourage in persons a grudging, but unwise, tolerance of intrusions into their personal lives. Do Canadians wish themselves to become conditioned to such intrusions? Complacency could lead to the further acceptance of what should be unacceptable intrusions. As one commentator argues:

"Drug testing is just one of a long list of training procedures that operate in the disciplinary technology of power to inculcate automatic docility in the work force. Because it is relatively recent, this part of the drill has engendered public debate. Newer or more intrusive procedures, such as blood tests for the AIDS virus or lie-detector tests, are even more controversial. Many other training procedures, such as punching a time clock or taking various sorts of aptitude or skill-verifying tests, have become so habitual that they are no longer questioned or even noticed. When giving a urine sample becomes as routine as divulging ones marital status or social security number on a farm, it will be fully integrated into the drill that creates automatic docility."Footnote 24 - the impact of drug testing on organizational morale. Obliging employees and job applicants to submit to drug testing may cause deep resentment (some employees, however, may welcome drug testing programs that might enhance their own safety by detecting potentially impaired co-workers). Employer-employee relations do not need the additional strains that drug testing will bring.Footnote 25This may particularly be the case when the test searches, not for on-the-job impairment, but (as most tests can only do) simply for drug use. Such testing often delves into the activities of employees outside working hours.

- the danger of inaccuracies creeping into the process. Drug testing is a highly technical process. It requires highly skilled personnel to perform repetitive tasks. Simple boredom may result in unacceptable levels of error. Add to this the expense associated with confirmatory testing (an especially important consideration in the private sectorFootnote 26 ), and the result may be a recipe for mediocrity in testing.

To confirm that a person has ingested the drug being tested for, two tests are necessary. The first is a screening test—commonly the EMIT (Enzyme Multiplied Immunoassay Technique). If the screening test produces a positive result, a confirmatory test must be performed. Several confirmatory tests are available, but the GC/MS (gas chromatography with mass spectrometry) appears to be the most reliable.

Even with confirmatory testing, however, drug-free employees may find themselves placed under suspicion or have their careers ruined on the basis of the initial screening test. David Linowes reports in Privacy in America: Is Your Private Life in the Public Eye?:Footnote 27

"In his book The Great Drug War (1987), Dr. Arnold Trebach … says that "approximately 5 million people were tested this year in America" for drug use. He further states that while drug-testing companies, such as Syva Company of Palo Alto—makers of the EMIT test—claim a 95 percent accuracy rate, the rate would be more like 90 percent when the tests are performed by people other than Syva’s own technicians. According to Trebach, 'If there were a false reading rate of 10 percent, with half false positives and half false negatives, this could mean that approximately 5 percent of the approximately 5 million people tested this year in America were accused improperly of being drug users. Thus, there is a good chance that 250,000 employees were placed under suspicion or had their careers ruined for no reason."'

Confirmatory testing, such as the GC/MS, has the theoretical capacity for virtually perfect accuracy. GC/MS testing could clear up the mis-labelling that occurs with false positives determined through the EMIT screening test. Theory and practice, however, may not coincide. As the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association has noted:

"There is nearly unanimous consensus that if one is willing to spend the money to acquire the appropriate technology, train and motivate the operators, and to ensure meticulous record keeping, specimen handling and chain of custody and reporting, accurate and specific identification of drug metabolites can be achieved."

…

"Though the potential for virtually perfect accuracy is admitted (using GC/MS and given flawless conditions, adequate time and funds, and strictest adherence to all procedures), one U.S. Court has held that even confirmation by GC/MS is insufficient because of the possibility of human error."

…

"Dull, repetitive work that nonetheless requires highly skilled technicians [as GC/MS testing does] is a fertile breeding ground for human error—most tests will be negative, punctuated by the occasional, more interesting, positives. The livelihoods of those being tested rest upon extreme diligence in routine tasks such as cleaning glassware, affixing and recording labels, reading meters, transcribing numbers, key punching and filing. Testing labs vigorously claim to have solved this problem, but nothing in the published error rates to date justifies these claims. Research on similar work conditions elsewhere would lead one to suspect that the error rates will continue to be unacceptably high."Footnote 28 - testing methodologies must be developed and procedures established to ensure that samples will not be adulterated or mixed with other samples (the "chain of custody" issue). Sophisticated personnel must be hired and trained to collect samples and perform tests. Threshold concentrations must be set. Officials must decide what drugs to test for, and what to do with the results. They must ensure the reliability of the testing facilities—a time consuming and expensive process in itself. Storage facilities will be needed to keep samples in case of challenge. Litigation will inevitably result from the imposition of testing programs. The resulting information—an indication of past drug use—may often not be sufficiently useful to warrant the problems and costs associated with the testing process in the first place.

- urinalysis is highly intrusive. It not only requires the surrender of a body fluid, but, to prevent the subject adulterating or substituting the sample, it may be necessary to observe the subject's genitals as he or she urinates. The disposal of body wastes is generally considered a highly personal act. Urinalysis may expose this act to close visual scrutiny. Such observation is intrusive and humiliating. Indeed, for urinalysis, it could be necessary for the subject to be nude while urinating (and possibly under direct observation as well).Footnote 29 Adulterating substances could otherwise be hidden in clothing.

Technology may one day provide a test that will avoid direct observation of this highly personal act. Perhaps hair analysis will achieve suitable credibility so that only a single strand of hair will be required. Still, any process of acquiring personal information from a person's biochemistry is intrusive. Privacy considerations outweigh all but the most powerful justifications for testing. As Mr. Justice La Forest stated in a 1988 Supreme Court of Canada decision, R. v. Dyment: "[T]he use of a person's body without his consent to obtain information about him, invades an area of personal privacy essential to the maintenance of his human dignity".Footnote 30

The intrusiveness of testing does not end with the surrender of a body substance and the possibility of direct observation. Test subjects may be required to disclose their use of other drugs (prescription drugs and over the-counter inhalants, for example) that could cause a positive test result. This in turn may disclose information about the health of the person.

Other tests (not connected to drug testing) could be performed on urine provided for drug testing, identifying conditions that the subject does not want to disclose (diabetes or pregnancy, for example) or does not even know about. - the substitution effect. Persons likely to be tested for the use of one substance (for example, marijuana) may simply switch to an equally harmful drug that is not being tested for. Testing for illicit but not licit drugs encourages this type of behaviour. Users of illicit drugs may simply switch to alcohol. If the object of the testing program is to reduce the use of illicit drugs, this result is appropriate. If, however, the object is to reduce impairment by any drug or to reduce safety or health risks, the substitution effect may create a more serious problem than existed before testing began.Footnote 31

- creation of an underclass of chronic unemployables. Employees or applicants who test positive may become unemployable, even though they can safely and competently perform their job duties, and even if they have ceased using the drugs in question. Their past may haunt them long after they have "gone straight".

- creation of a false sense of security. By focussing on drug use, government and employers may overlook other causes of incidents or accidents. Accident investigators who find impairment by drugs as a possible cause, for example, may be tempted to ignore other causal factors and perpetuate the danger. They will have found an easy scapegoat. A 1988 Canadian Labour Congress submission to the Standing Committee of Transport on Bill C-105 stressed this point:

"Drug testing is a 'red herring' and is designed explicitly to draw attention away from other causes of health and safety hazards that cause accidents. It is an attempt to shift the burden of responsibility for safety problems onto employees and to hide employer failure to ensure safe and healthy workplaces."

''Alcohol and drug testing takes the employer and the government off the hook. It gives the appearance that they are doing ‘something’ about safety."Footnote 32 - drug testing may be the "solution" to a problem that has been exaggerated. This argument has two dimensions. First, is there a problem that needs a solution? Second, if there is, will drug testing help to solve it?

Alcohol abuse is implicated in thousands of traffic deaths yearly. Is there evidence that other drugs are causing significant problems relating to job performance, on-the-job safety or public safety? In the absence of such evidence, are there other problems caused by drug use? If the answer is no, why test?

Even if the answer is yes—that there are problems caused by drug use—will testing contribute to solving them? - lack of procedural safeguards. Some forms of drug testing are as intrusive as the exercise of law enforcement powers by the state. Yet they are subject to few of the safeguards available to protect people from the exercise of other investigative powers by the state. An employer might randomly test employees without any reasonable "individualized" suspicion that they use or are impaired by drugs. When such a power has been exercised by government institutions in Canada or the United States, it has often been challenged as unconstitutional. As yet, however, the Supreme Court of Canada has not considered the constitutionality of urinalysis. It has, however, spoken in support of the integrity of the person in the face of law enforcement acti.ons by the state.Footnote 33

Private sector testing has the potential to be even more intrusive; few laws, apart from human rights codes, govern private sector testing and how the resulting information is used. The dangers of "free-form" private sector testing—testing with no or few controls to safeguard those being tested and with a lack of concern for human dignity—are real. - The impact on personal autonomy. Drug testing coerces conformity—abstention from consuming psychoactive substances, both legal and illegal, for example. It restricts autonomy. To what extent should governments or employers be permitted to use the coercive power of drug tests to restrict the consumption of substances? Is it sometimes right to coerce (to prevent impaired driving, for example), and sometimes wrong (to regulate the simple consumption of substances away from the workplace in situations that create no danger for others)?

c) Conclusion

Testing imports an aura of oppression and Big-Brotherhood. Some forms of testing—breathalyzer tests to detect impaired driving or operation of vessels or aircraft, for example—have broad public support. But would a knowledgeable public accept testing in circumstances that may do little to enhance public safety?

Testing supposes an employer's (or government agency's) right to exercise substantial control over individuals and to intrude into some of the deepest recesses of their lives. The technology of drug testing is being allowed to shape the limits of human privacy and dignity.

The situation should be the other way around. Notions of respect for individual privacy and autonomy should place limits on the intrusions which technology will be permitted to make into personal lives. In other words, the uses of technology should not limit human rights; human rights should limit the uses of technology.

PART III: DRUG TESTING AND THE Privacy Act

a) Introduction

The Privacy Act was enacted in 1983, setting out principles of "fair information practices". Among other obligations, it requires government institutions to:

- collect only the personal information needed to operate its programs;

- collect the information directly from the individual concerned, whenever possible;

- tell the individual how it will be used;

- keep the information long enough to ensure an individual access; and

- take all reasonable steps to ensure its accuracy and completeness.

The Privacy Act generally does not compel collection, use or disclosure (except dis closure to meet access requirements) of personal information; it merely permits it.

The Act defines "government institution" as any department, ministry of state, body or office of the Government of Canada listed in the schedule to the Act. Currently, the Act covers some 150 institutions. It does not apply to the private sector.

b) Specific elements of the Privacy Act and their application to drug testing

(i) Personal information

The Act applies only to "personal information". Section 3 defines personal information as:

"information about an identifiable individual that is recorded in any form including, without restricting the generality of the foregoing, …information relating to the … medical, criminal or employment history of the individual …".

In the context of drug testing the Act covers the following personal information:

- test results;

- the fact of taking the test, being advised, asked or ordered to take the test, asking to be tested, or refusing to be tested, and any discussions about the test;

- peripheral information such as medical or physical conditions that may influence test results, and other medications or substances used or ingested by the test subject;

- information suggesting cause for testing (for example, the apparent impairment of a person while on duty, the fact of being charged with possession of an illicit drug, or disclosure of drug use by the person to a co-worker);

- any treatment programs relating to drugs that the person may have entered, been advised or ordered to enter, or refused to enter; and any disciplinary measures or criminal charges relating to drugs.

(ii) Collection of personal information

Section 4 of the Act states:

"No personal information shall be collected by a government institution unless it relates directly to an operating program or activity of the institution."

An institution wanting to test cannot, by simply creating a testing program, comply with section 4. Implicit in section 4 is the requirement that no such information is to be collected unless (1) the collection is part of an activity or program falling within the statutory mandate of the institution and (2) the collection is a necessary element of a mandated program or activity. Even if the test subject consents, the collection of information by testing will not be valid unless it meets these two conditions.

Specific statutory authority for an institution to conduct drug testing of employees or clients will, of course, ensure compliance with section 4.

Despite the fact that section 4 does not require specific statutory authority for any form of information collection, the additional safeguard of Parliamentary approval is highly desirable for highly intrusive forms, such as urinalysis. Indeed, it is our view that elected officials should be given the opportunity to carefully weigh the evidence as to whether the public interest in detecting drug use through mandatory drug testing outweighs, in specific cases, individual privacy rights. This view is consistent with our previous recommendation in AIDS and the Privacy Act that mandatory HIV antibody tests be permitted only with Parliamentary authority.

Without specific statutory authority to collect personal information through drug testing, determining compliance with section 4 becomes more difficult. It involves assessing the necessity principle and weighing the public interest in collection against the privacy intrusion involved.

A) Assessing the justifiability of intrusions caused by testing programsThe principal privacy issue flowing from drug testing is not whether testing is intrusive. It is. Urinalysis is particularly intrusive, requiring as it may either a pre-test physical search, the direct observation of an intimate bodily function, or both.Footnote 34 The principal issue is in what circumstances the intrusions occasioned by testing are justified.

Despite the limited inferences that can be drawn from test results and despite the intrusiveness of drug testing, the Privacy Act does not prohibit all drug testing. However, we have concluded—as did the Standing Committee on National Health and Welfare—that only in exceptional cases in which drug use constitutes a real risk to safety is drug testing justifiable.

The following justifications alone are not sufficient under section 4 of the Privacy Act to legitimize drug testing: the desire to promote efficiency, economy and honesty, the desire to reduce the demand for illicit drugs and the desire to comply with foreign testing requirements.Footnote 35 Although specific legislation could permit or require testing in these circumstances, such legislation would not be appropriate. Nor would it likely comply with the Charter.

Collecting personal information by mandatory drug testing, without cause to suspect drug use by or impairment of a person or within a group, and with no evidence to suggest that drug use or impairment poses a threat to public safety, would infringe section 4 of the Privacy Act. Such testing would violate the privacy of everyone in the group ordered to take the test. It presumes guilt without setting any threshold standard of reasonable belief or suspicion before the test is taken. It subjects the majority who are not using drugs to invasive procedures designed to single out the minority. Such testing is a fishing expedition, not a justifiable search. Moreover, few meaningful conclusions can be drawn from the test results. Yet those testing positive can suffer significant detriment.

At the other end of the continuum is testing where there is reason (or "cause") to believe that a person is impaired by legal or illegal drugs, the impairment poses a threat to public safety and there is no other effective means of reducing the threat (for example, it may not be possible to supervise the person closely). This testing is the easiest to justify (although urinalysis is still deficient, since it cannot measure present drug use or impairment).

It is not a fishing expedition. It is aimed at a person whose behaviour suggests impairment. It therefore does not subject large numbers of people to testing. Instead, it relies on specific evidence to identify a limited number of persons. Testing programs at this end of the continuum could more easily be brought into accord with section 4 of the Privacy Act.

Under the following circumstances, drug testing would be justifiable under the Privacy Act:

(1) Testing because of group behaviour as a whole:

A reliable survey or other method of monitoring may have identified that a given group (police officers, pilots or inmates, for example) has a drug-related problem. It may be impractical to counter the problem through a testing program based on reasonable suspicion about an individual (perhaps because individual activities cannot be adequately supervised or because the visible impairment caused by the drug use in question is too subtle to observe). In this case, the only (and still imperfect) course of action may be to test randomly.

The collection of personal information through random mandatory testing of group members on the basis of the behaviour patterns of the group as a whole may be justifiable, but only if the following conditions are met:

- there are reasonable grounds to believe that there is a significant prevalence of drug use or impairment within the group;

- the drug use or impairment poses a substantial threat to the safety of the public or other members of the group;

- the behaviour of individuals in the group cannot otherwise be adequately supervised;

- there are reasonable grounds to believe that drug testing can significantly reduce the risk to safety; and

- no practical, less intrusive alternative, such as regular medicals, education, counselling or some combination of these, would significantly reduce the risk to safety.

(2) Testing because of individual behaviour:

Most groups will not exhibit drug-related safety problems to the extent that would warrant random testing of group members. However, individual group members may still pose a safety risk if they are impaired by drugs. In such cases, it should be possible to collect personal information through mandatory testing when there is reasonable suspicion. A person might appropriately be tested if the following conditions are met:

- there are reasonable grounds to believe that the person is using or is impaired by drugs;

- the drug use or impairment poses a substantial threat to the safety of those affected by the person's actions;

- the person's behaviour cannot otherwise be adequately supervised;

- there are reasonable grounds to believe that drug testing can significantly reduce the risk to safety; and

- no practical, less intrusive alternative, such as regular medicals, education, counselling or some combination of these, would significantly reduce the risk to safety.

Recommendation 1

Government institutions should seek Parliamentary authority before collecting personal information through mandatory testing.

Recommendation 2

The collection of personal information through random mandatory testing of members of a group on the basis of the behaviour patterns of the group as a whole may be justifiable only if the following conditions are met:

- there are reasonable grounds to believe that there is a significant prevalence of drug use or impairment within the group;

- the drug use or impairment poses a substantial threat to the safety of the public or other members of the group;

- the behaviour of individuals in the group cannot otherwise be adequately supervised;

- there are reasonable grounds to believe that drug testing can significantly reduce the risk to safety; and

- no practical, less intrusive alternative, such as regular medicals, education, counselling or some combination of these, would significantly reduce the risk to safety.

Recommendation 3

A person who is not a member of a group which exhibits drug-related problem behaviour might appropriately be tested if the following conditions are met:

- there are reasonable grounds to believe that the person is using or is impaired by drugs;

- the drug use or impairment poses a substantial threat to the safety of those affected by the person's actions;

- the person's behaviour cannot otherwise be adequately supervised;

- there are reasonable grounds to believe that drug testing can significantly reduce the risk to safety; and

- no practical, less intrusive alternative, such as regular medicals, education, counselling or some combination of these, would significantly reduce the risk to safety.

Recommendation 4

Since drug testing programs designed primarily to promote efficiency, economy or honesty, or to reduce the demand for illicit drugs, would not satisfy recommendations 2 or 3, such programs would violate the Privacy Act.

Because public safety should be the principal consideration behind drug testing, tests should not distinguish between legal and illegal drugs. The focus instead should be on the harm caused by any substance that impairs.

Recommendation 5

Testing programs should not distinguish between legal and illegal drugs that can impair.

Direct collection and the duty to inform: section 5: Section 4 of the Act permits government institutions to collect personal information in defined circumstances only. Section 5 imposes additional limits on collection. These are the duty to collect information directly and to inform about the purpose of the collection.

Subsection 5(1) addresses direct collection. It states:

"5(1) A government institution shall, wherever possible, collect personal information that is intended to be used for an administrative purpose directly from the individual to whom it relates except where the individual authorizes otherwise or where personal information may be disclosed to the institution under subsection 8(2)."

The duty to collect directly in subsection 5(1) is not absolute. There are four exceptions. Subsection 5(1) permits indirect collection when direct collection is not possible or when the person to whom the information relates authorizes another form of collection. As well, the collection need not be direct if the personal information being sought may be disclosed to the institution under subsection 8(2). That subsection sets out several circumstances where a government institution holding personal information may disclose the information, including disclosure to another institution. Finally, the collection need not be direct if it would result in the collection of inaccurate information or would defeat the purpose or prejudice the use for which the information is collected (subsection 5(3)).

Using information "for an administrative purpose" simply means using the information in a decision making process that directly affects the individual (section 3). Thus, a government institution relying on information about a person's drug use to decide a person's suitability for employment would be using the information for an administrative purpose.

Subsection 5(1) is, in our view, a legalistic way of saying, "If you want to learn something about a person, ask the person", unless the law authorizes another mode of collection. The section clearly contemplates having the individual volunteer his or her personal information to the fullest extent possible.

The collection of information through drug testing would only be considered direct collection under subsection 5(1) if the test subject truly volunteered to be tested. Mandatory drug testing therefore would be considered an indirect collection and would only comply with section 5 if it fell within one of the exceptions identified by the section.

Recommendation 6

Government institutions must wherever possible collect personal information used for an administrative purpose and relating to drug use or impairment directly from the individual (that is, if the person volunteers). Collection may be indirect (that is, from other sources or without the person's consent) in the following circumstances:

- when it is not possible to collect the information directly;

- when the person to whom the information relates consents to another method of collection;

- when the personal information may be disclosed to the institution under subsection 8(2) of the Privacy Act; or

- when direct collection might result in the collection of inaccurate information or defeat the purpose or prejudice the use for which the information is collected.

Informing about the purpose of the collection: Subsection 5(2) of the Act imposes the duty to inform a person from whom personal information is being collected of the purpose of the collection:

"5(2) A government institution shall inform any individual from whom the institution collects personal information about the individual of the purpose for which the information is being Collected."

The institution is required to inform of the purpose only where the information is collected directly (voluntarily, in the case of drug tests) from that individual. If the personal information is not collected directly, subsection 5(2) imposes no duty to inform. Nor is it necessary to inform a person from whom information is collected of the purpose if informing might result in the collection of inaccurate information or defeat the purpose or prejudice the use for which information is collected (subsection 5(3)). We recommend as a matter of policy, however, that even when information is collected indirectly, test subjects be informed of the purpose of the collection unless it would result in the collection of inaccurate information or defeat the purpose or prejudice the use for which the information is collected.

Recommendation 7

Even when subsection 5(2) of the Privacy Act imposes no duty on a government institution to inform about the purpose of the collection, test subjects should as a matter of policy be informed. Only if informing the test subject would result in the collection of inaccurate information or defeat the purpose or prejudice the use for which the information is collected should the purpose of the collection be withheld from the person.

(iii) Retention and disposal of personal information

When personal information is used for an administrative purpose, the Act sets out retention requirements. Once a urine, hair or other sample is taken from a person and identified as belonging to that person (normally by labelling a container holding the substance) it becomes personal information. Accordingly, the sample (and other personal information) used for an administrative purpose must be retained for a specified period. Subsection 6(1) reads:

"6(1) Personal information that has, been used by a government institution for an administrative purpose shall be retained by the institution for such period of time after it is so used as may be prescribed by regulation in order to ensure that the individual to whom it relates has a reasonable opportunity to obtain access to the information."

Subsection 4(1) of the Privacy RegulationsFootnote 36 states:

"4(1) Personal information concerning an individual that has been used by a government institution for an administrative purpose shall be retained by the institution

(a) for at least two years following the last time the personal information was used for an administrative purpose unless the individual consents to its disposal; and

(b) where a request for access to the information has been received, until such time as the individual has had the opportunity to exercise all his rights under the Act."

Consequently, a two year minimum applies for the retention of urine samples and the information relating to the samples.

A more troubling issue is the maximum period of retention. The appropriate maximum period may vary from case to case. However, positive test results retained by government should not be allowed to haunt persons many years after the test. It would be inappropriate for a government institution even to speculate that a person is a current drug user because of a positive test result from several years past. If the conditions for testing (set out in Recommendations 2 and 3) are met, the person could be retested to determine current use. If the conditions are not met, the person should not be retested.

Recommendation 8

Body samples and the personal information derived from those samples should be retained for the period prescribed by the Privacy Regulations, and be disposed of as soon as possible after the retention period has expired.

Subsection 6(3) imposes a duty to dispose of personal information in a certain way:

"6(3) A government institution shall dispose of personal information under the control of the institution in accordance with the regulations and in accordance with any directives or guidelines issued by the designated minister in relation to the disposal of such information."

Some personal information is more sensitive than other such information. A diagnosis of AIDS, for example, could have catastrophic consequences for the person affected if the information were released to the community. Information about a person's drug using habits, while perhaps not as sensitive as AIDS-related personal information, still merits strict safeguards. The release of the information could seriously impair a person's chance to obtain or hold employment. It could affect his relationship with co-workers or others in the general community. Given contemporary attitudes about drug use, discrimination is bound to flow from disclosure.

Even peripheral information—other "legitimate" drug use associated with a medical condition that had to be reported to clarify the results of a drug test, for example—could harm a person if released improperly. At the very least, it would be an entirely unwarranted disclosure of information which the person has a right to keep private.

Handling and disposal procedures should take into account the sensitivity of information related to drug testing. The Security Policy and Standards of the Government of Canada recognizes the sensitivity of personal information collected under the Privacy Act. Such information is considered "designated information" warranting enhanced protection.

Under section 5.7 (Appendix D), the Security Organization and Administration Standards, particularly sensitive designated information requires special security measures. Included is information concerning medical, psychiatric or psychological descriptions and information concerning a person's lifestyle. To identify particularly sensitive personal information, the Security Policy establishes an "injury" test. The information will be considered particularly sensitive if its disclosure, removal, modification or loss could reasonably be presumed to cause an invasion of privacy.

Using this injury test, information from drug tests or information suggesting drug use could easily be seen as particularly sensitive personal information. Among the special security measures that must apply to such information are those dealing with storage, processing, transmittal and destruction.

Those responsible for the handling and disposal of such information must comply with the Security Policy and Standards of the Government of Canada.

Recommendation 9

Procedures for the handling and disposal of personal information collected under the Privacy Act should reflect the sensitivity of the information. At a minimum, personal information relating to drug tests should be accorded physical protection at level B, as defined in the Security Policy and Standards of the Government of Canada.

(iv) Accuracy, currency and completeness of personal information

The Privacy Act imposes quality control standards on the personal information used by government institutions. Subsection 6(2) states:

"6(2) A government institution shall take all reasonable steps to ensure that personal information that is used for an administrative purpose by the institution is as accurate, up-to-date and complete as possible."

Note that subsection 6(2) does not require perfection. The obligation is to take all reasonable steps to ensure that the information collected is as accurate, up-to-date and complete as possible.

As accurate as possible: Ensuring that information relating to drug testing is as accurate as possible has two dimensions. First, the testing procedure should correctly identify those who have or have not used drugs in the "window of detection" period to which the test applies. Second, urinalysis results should be understood to refer to past use only, not present use or past or present impairment. Nor can urinalysis results be used to measure the quantity of the drug consumed.

Over time, drug tests will improve with changes in technology. Whatever the technology, drug testing should aim for the following:

- the greatest likelihood that a person who has not taken a drug during the test window period will test negative (the test must be highly "specific") and

- the greatest likelihood that a person who has taken a drug during the test window period will test positive (the test must be highly "sensitive").

In practice, there is a tradeoff between sensitivity and specificity. A highly sensitive test may result in a large number of false positives. A highly specific test may result in a large number of false negatives.

Urinalysis, today's preferred testing method, requires two tests to confirm positivity—a screening test and a confirmatory test. A screening test is highly sensitive. It may have an unacceptably high level of false positives if used alone. Accordingly, a positive screening test should never be used for an administrative purpose other than to suggest the need for a confirmatory test. National Health and Welfare should identify the appropriate screening and confirmatory tests to be used.

A negative screening test result, however, need not be confirmed before it is used for an administrative purpose as defined in the Privacy Act.

It might be argued that a negative urinalysis result should be recorded as indicating any of the following: that the person has not taken the drug being tested for, that the person took the drug, but not sufficiently often or in sufficient amounts to test positive, or that the person took the drug, but the sample was taken after the drug or its metabolites had passed from the person's system.

The ambiguity inherent in negative test results may lead those relying on the record to infer that the person in fact was a drug user, but escaped detection for one of the reasons set out above. Thus, a large number of persons who tested negative simply because they did not take the drug in question might be unfairly judged. By whatever means a government institution records negative test results, it should seek to ensure that the user of the information will be aware of the danger of making an improper inference about the meaning of a negative test result. Otherwise, anyone who takes a drug test could fall under a cloud of suspicion, whether the result is positive or negative.

Recommendation 10

Government institutions should not use positive urinalysis results for an administrative purpose unless the results have been supported by confirmatory testing according to accepted scientific/ medical protocols approved by National Health and Welfare.

Government institutions may use negative screening test results for an administrative purpose without conducting confirmatory testing where the screening test has been conducted according to acceptable scientific/medical protocols which are approved by National Health and Welfare from time to time.

Recommendation 11

Government institutions should seek to ensure that those interpreting negative test results do not go beyond the inferences scientifically supported by the test.

Because of the complexity of the testing process—be it urinalysis or some other test—a government-wide testing protocol should be developed. National Health and Welfare is currently developing such a protocol, but it has not yet made it public.

Recommendation 12

Because of the complexity of the testing process—be it urinalysis or some other process—a government-wide testing protocol should be developed. At a minimum, the protocol should establish procedures for the following:

- sample collection, including procedures to permit the giving of samples in private, wherever possible;

- the appropriate screening and confirmatory tests to use for each drug being sought;

- threshold concentrations for each drug test (to determine when a result is "positive");

- chain of custody procedures to prevent tampering with or exchange (deliberate or accidental) of samples;

- standards for testing laboratories;

- the meaning of positive or negative test results; and

- security procedures governing the personal information relating to drug testing.

The need for repeat testing to ensure accuracy: Urinalysis can address only the past use of a drug during the "window of detection" period. Repeat testing would be necessary even to be reasonably certain that a person has remained drug free or is continuing to use drugs; it could be necessary to test several times a month, depending on the drug. Even then, the test would not reveal drug consumption in preceding hours, as the metabolites to which urine tests react may not yet have entered the urine.

As complete as possible: Institutions should take reasonable steps to ensure that personal information is as complete as possible. In the context of drug testing, a positive test result which may have caused by a substance other than the drug being tested for should always be reported with the test result. Any information indicating that legitimate substances may have caused the positive result should be included with the test result. In these circumstances, the test result should not be relied on as indicating use of the drug being tested for.

Recommendation 13

When a person tested for a given drug may have consumed other substances which could lead to a positive test result for that drug, such information should accompany the test result. The test result should not in such circumstances be accepted as indicating that the person has used the drug being tested for.

As up-to-date as possible: A urinalysis result indicating that a person has in the past used the drug tested for can be considered "as up-to-date as possible" if the information is used only to confirm past consumption. The institution using the positive urinalysis result should understand that the result indicates past drug use, not present use. To ensure the currency of information about drug use, the institution may need to re-test the person. Re-testing should occur, however, only if the conditions contained in Recommendations 2 or 3 are met.

Recommendation 14

An institution using urinalysis results for an administrative purpose should ensure that those using the results understand their meaning. A positive urinalysis result should not be used to identify present use, or past or present impairment by a drug. The institution should also ensure that those using the results understand that urinalysis cannot measure the quantity of the drug consumed.

(v) Use of information relating to drug testing

Section 7 of the Act governs the use of personal information under the control of a government institution:

"7. Personal information under the control of a government institution shall not, without the consent of the individual to whom it relates, be used by the institution except

(a) for the purpose for which the information was obtained or compiled by the institution or for a use consistent with that purpose; or

(b) for a purpose for which the information may be disclosed to the institution under subsection 8(2)."

The relationship between subsections 7(b) and 8(2) requires explanation. Subsection 8(2) permits government institutions to disclose information for certain purposes. Subsection 7(b) permits the institution receiving the disclosed information to use it for those purposes.

Specific legislation may permit inconsistent uses. For example, legislation might permit the use of test results that determined a person's suitability to operate an aircraft as a foundation for criminal charges. (Such legislation might violate the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, but it would not offend the Privacy Act.)

Restrictions on use: Information generated by or relating to drug tests should be used for three purposes only, unless the person to whom the information relates consents otherwise:

- for the use for which the information was obtained or compiled (to assist in performing drug tests or analyzing test results);

- for a use consistent with that purpose; or

- for a purpose for which the information may be disclosed to the institution under subsection 8(2).