Annual Report to Parliament 2011 on the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act

This page has been archived on the Web

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Privacy for Everyone

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

112 Kent Street

Ottawa, Ontario

K1A 1H3

(613) 947-1698, 1-800-282-1376

Fax (613) 947-6850

TDD (613) 992-9190

© Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada 2012

Cat. No. IP51-1/2011

1910-0051

Follow us on Twitter: @privacyprivee

June 2012

The Honourable Noël A. Kinsella, Senator

The Speaker

The Senate of Canada

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A4

Dear Mr. Speaker:

I have the honour to submit to Parliament the Annual Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada on the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act for the period from January 1 to December 31, 2011.

Sincerely,

(Original signed by)

Jennifer Stoddart

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

June 2012

The Honourable Andrew Scheer, M.P.

The Speaker

The House of Commons

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A6

Dear Mr. Speaker:

I have the honour to submit to Parliament the Annual Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada on the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act for the period from January 1 to December 31, 2011.

Sincerely,

(Original signed by)

Jennifer Stoddart

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

The Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act, or PIPEDA, sets out ground rules for the management of personal information in the private sector.

The legislation balances an individual's right to the privacy of personal information with the need of organizations to collect, use or disclose personal information for legitimate business purposes.

PIPEDA applies to organizations engaged in commercial activities across the country, except in provinces that have substantially similar private sector privacy laws. Quebec, Alberta and British Columbia each have their own law covering the private sector. Even in these provinces, PIPEDA continues to apply to the federally regulated private sector and to personal information in inter-provincial and international transactions.

PIPEDA also protects employee information, but only in the federally regulated sector.

Message from the Commissioner

Teenagers are growing up in a very different world than I did.

Today’s youth have an unprecedented ability to communicate. This first wave of what some have called the “Facebook generation” has latched onto the online world to stay in touch with friends – sharing new YouTube videos and the latest hit songs, making plans to hang out, and talking about what’s happening in their lives.

I did many of the same things with my school friends – except that I did all this in person or over the phone shared with other family members.

The big difference about what I used to do and now is that there is no record of what my friends and I gossiped about back then. That was also the case for my own children – who are still only in their 20s.

But that’s clearly not the case for anyone who is now a teenager.

All of that online communication creates a permanent record – and that could carry risks to their privacy and to their reputations. Not just today, but perhaps even more in the future.

Teenagers are expected to make mistakes - it’s a natural part of growing up.

The fact that electronic records of many of the mistakes of today’s youth will persist for decades to come is cause for deep concern.

Indeed, a host of perils threaten the privacy and personal information of children and youth – one of the reasons that we have made them a key focus of this report.

Not only are the young usually the first to embrace any new kind of digital communication, they are also often unsuspecting about the potential privacy intrusions that can accompany such novel technologies.

And there’s another good reason why our efforts to protect the personal information of children and youth warrant their own chapter. They constitute an important example of where my Office is providing leadership on a priority privacy issue.

Providing such leadership is a commitment I made to MPs and Senators when I was reappointed to a three-year term as Privacy Commissioner of Canada. It was one of three areas on which I promised to focus; the other two were supporting informed privacy decision-making and improving service delivery to Canadians.

Now, one year into my renewed mandate, seems an appropriate point to review progress in fulfilling those commitments.

Significant Privacy Issues

First, leadership on significant privacy issues. As described later in this report, my Office has been particularly active in 2011 in the area of children and youth, creating a wealth of new outreach materials, funding innovative research and reviewing the effects of surveillance on the young.

We also wrapped up a comprehensive investigation into a complaint about privacy concerns related to a social networking website that specifically targeted young people. This first OPC investigation of a youth-oriented social networking site was highly complex, resulting in a detailed Report of Findings of some 100 pages, with 24 recommendations.

However, many of the problems with the site could have been avoided if only privacy considerations had been taken into account back when the operation was being designed and launched. For that reason, my Office considers that this particular investigation ought to serve as “lessons learned” for everyone engaged in handling the personal information of youth.

Another area in which we also provided privacy leadership was the burgeoning use of online behavioural advertising. While the term itself may be unfamiliar, almost all Canadians who go online will have seen such advertising.

Officially, online behavioural advertising is defined as the practice of tracking a consumer’s online activities in order to deliver advertising geared to that consumer’s inferred interests. What it means in practice is that Internet ad networks follow you around online, watching what you do so they can serve you targeted ads.

Late in 2011, we published guidance about how the parties involved in – or benefiting from – online behavioural advertising can ensure that their practices are fair, transparent and in compliance with the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA).

We specifically pointed out that organizations engaged in online behavioural advertising should avoid tracking children – or tracking on websites aimed at children – since meaningful consent may be difficult to obtain.

Yet another area of providing leadership on a priority privacy issue during the year was the “lawful access” legislation which had been announced by the Government (and which was eventually introduced as Bill C-30 early in 2012.) This legislation would have obvious impacts on the telecommunications industry. Following up on earlier mutual representations with provincial and territorial commissioners responsible for privacy, in October I sent an open letter to Public Safety Minister Vic Toews outlining my concerns that the expanded surveillance regime proposed in the legislation would have serious repercussions for privacy rights.

Informed Privacy Decisions

The second topic on which I committed to focus in my renewed mandate was supporting informed privacy decision-making by Canadians, organizations and institutions.

In May, my Office laid a solid foundation for this effort by publishing a final report on extensive public consultations the previous year about online tracking, profiling and targeting and cloud computing. From what we learned in those consultations flowed such things as tip sheets about cookies and cloud computing, a speakers series spotlighting frontier privacy challenges, the work on children and youth, the online behavioural advertising guidance and some of the questions in our biennial public opinion survey.

But that was by no means the sum of my Office’s efforts to make sure that Canadians develop strong digital literacy skills and better understand privacy rights.

For lawyers, we provided a handbook covering the privacy issues they were most likely to encounter during litigation and the running of a law office. For small businesses, we authored a set of DIY articles on protecting their valuable information – including personal details about customers – from online threats.

Working together, the OPC and its counterparts in Alberta and British Columbia also devised an innovative, online tool which allows organizations to assess the personal information safeguards necessary in records management, network security, continuity planning and 14 other operational areas.

Service Delivery

My third commitment was to focus on improving service delivery to Canadians. This is where the rubber truly hits the road in my Office, led by the day-to-day handling of information requests and complaints.

Streamlined procedures and the benefits of experience continued to yield improvements in our handling of complaints in 2011. The average time to deal with an accepted complaint dropped from more than 15 months in 2010 to just above eight months, significantly below the 12-month requirement in the Act.

A major contribution to this performance improvement can be traced to our greater use of an early resolution process which sidesteps an official investigation for selected complaints. By working with both the complainant and the respondent organization, our early resolution officers were able to successfully clear up more than 90 percent of these cases this process handles – without resorting to a full investigation.

And to continue to meet the needs and expectations of Canadians in the rapidly evolving digital environment, we strengthened our technology laboratory, which provides expert support to our audits and investigations and will also support the OPC’s responsibilities under Canada’s new anti-spam legislation.

As an Officer of Parliament, I have a special responsibility to Parliamentarians. The Assistant Privacy Commissioner and I, as well as other senior officials from my Office, We appear before committees, examine legislation for privacy implications, submit comments and have numerous informal interactions with Parliamentarians and staff.

This 2011 Annual Report contains many more examples of how we have delivered on the commitment to these three focus areas.

Making a Difference

However, the overarching question must be: Are we making a difference?

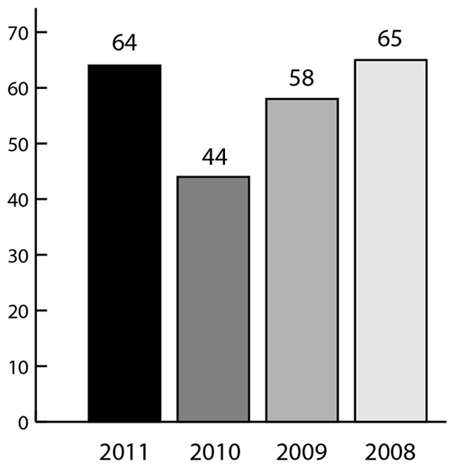

The answer is that, 10 years after PIPEDA became law, there is encouraging evidence that the OPC has had a positive impact on the privacy landscape. According to public opinion surveys commissioned by the OPC, the proportion of Canadians saying they feel they have less protection of their personal privacy in daily life than a decade previously has declined, from 71 percent in 2006 to 61 percent in 2011.

I believe that the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada deserves some of the credit for this change in public attitudes.

Recent years have brought continual challenges to the OPC and the first-class team of professionals here has consistently upped its game. The year 2011 was no exception and I am fortunate to work with such committed, hard-working and imaginative people. These include my indispensable Assistant Commissioner, Chantal Bernier, whose unfailing enthusiasm and intellectual curiosity are a source of constant inspiration.

Despite the welcome change in public attitudes, however, the proportion of Canadians telling the survey that protection of personal privacy will be one of the most important issues facing the country over the next 10 years has remained essentially unchanged from 2006 to 2011, at two-thirds.

To me, the explanation for this apparent paradox is straightforward.

Canadians appreciate that more is being done to protect their privacy and personal information. Yet they also understand that new challenges mean that still more must be done.

Prominent among those challenges is the rise of what is being called Big Data. In essence, this refers to the ability brought about through technological advances to gather more data than would have been conceivable just a few years ago and then sift through it, looking for patterns.

Benefits and Dangers

There’s no denying some potential benefits to society from Big Data. To take a somewhat prosaic example, Google is now able to spot flu outbreaks in North America days faster than national health authorities by flagging clusters of online inquiries about symptoms and remedies.

This undoubted public health benefit was quickly taken up by commercial interests. An article in the New York Times described how a A large marketing firm devised advertisements for a behind-the-ear thermometer which were sent to smartphones loaded with certain apps that collect basic details about the users, including their gender and whether they are parents. So the thermometer ad was specifically targeted at smartphones used by mothers of young children.

In addition, the ad was sent only to smartphones being used in regions where Google detected a flu spike and where the mothers were within three kilometres of retailers carrying the thermometer. Tapping the onscreen ad took the smartphone user to a product page with an informational video and a list of nearby retailers.

Some may find such personalized tracking by advertisers “creepy,” others might welcome targeted ads as relevant and helpful.

Whatever your view, this is only the beginning of where Big Data is going.

The many new forms of digital communication between individuals – texting, emails, instant messaging and so on – are all very easily computer readable and therefore subject to complex analysis by computers. Sophisticated software can track individuals through their unique identifying device numbers – revealing their location in time and place, their Internet activities and their interactions with other people with whom they form a “community.”

As Leonard Cohen prophetically sang in “The Future” two decades ago, in years to come, “won’t be nothing you can’t measure anymore.”

Information Explosion

Until recently, the definition of personal information was fairly clear-cut for most people. It was what you’d find on a tombstone, plus traditional things like address, phone number, Social Insurance Number, driver’s licence and passport, and so on. Now people scatter digital crumbs containing personal information as they move through their online existence.

And the volume of those crumbs is mounting at an explosive rate.

My Office has already laid down guidelines for the use of such information in the specific instance of online behavioural advertising. But there will undoubtedly be uses we can’t currently foresee which will have serious implications for privacy.

That’s why, in the end, improving the digital literacy of all Canadians is so crucial.

Jennifer Stoddart

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

| PIPEDA information requests received | 5,236 |

| PIPEDA formal complaints accepted | 281 |

| PIPEDA early resolution cases successfully closed | 116 |

| PIPEDA investigations closed | 120 |

| Draft bills and legislation raising PIPEDA issues reviewed for privacy implications | 11 |

| Policy guidance documents issued | 5 |

| Parliamentary committee appearances | 5 |

| Other interactions with Parliamentarians or staff (for example, meeting with MPs or Senators) | 33 |

| Speeches and presentations delivered | 143 |

| Contribution agreements signed | 8 |

| Visits to main Office website | 1,843,686 |

| Visits to Office blogs and other websites (including OPC blog, youth blog, youth website, deep packet inspection website and YouTube channel) | 871,698 |

| Total | 2,715,384 |

| “Tweets” sent | 416 |

| Publications distributed | 11,811 |

| News releases issued | 37 |

Note: Unless otherwise specified, these statistics also include activities under the Privacy Act, which are described in a separate annual report.

Chapter 1

Overview of 2011

1.1 Serving Canadians

Information Requests

During 2011, our Office handled more than 5,200 phone calls, emails and letters from Canadians about privacy issues in the private sector covered by PIPEDA. Issues related to the use of Social Insurance Numbers remained a common reason that people contact us for information. As well, we are receiving a growing number of requests related to online issues, particularly with respect to social networking sites. More details appear in section 4.1.

Complaints

In yet another move to speed up service to Canadians, we created a dedicated Intake Unit, which initially reviews all written complaints received. If necessary, the Unit follows up wih the complainant to clarify our understanding of the complaint and gather any additional information or documents necessary so we can launch an investigation as quickly as possible.

This streamlined screening has helped to reduce the average times of an investigation. Combined with other complaint handling improvements such as the increased use of early resolution approaches, the result has been a further drop in the time it takes to handle all formal complaints – now down to an average of 8.2 months – well below the 12-month requirement set out in PIPEDA. (See Appendix 2 for details.)

We accepted a total of 281 formal complaints in 2011, compared to 207 in 2010. Possible explanations for this 35 percent rise include an increased complexity of issues raised, heightened public awareness of privacy rights or more intense interaction with business in the digital economy.

In 2011, we completed 125 early resolution cases and all but nine were satisfactorily resolved without opening a formal investigation.

Complaint Investigations

We completed 120 formal investigations into complaints related to the private sector in 2011. This is a significant decrease from 2010, when we completed 249 investigations, in the culmination of a two-year effort to clear a backlog of complaints.

We have made privacy issues related to children and youth a focus of this year’s report and summaries of the relevant complaint investigations are included in Chapter 2.

Investigations related to financial privacy, online privacy and biometrics appear in Chapter 3, a survey of the 2011 privacy landscape. Information on still other complaint investigations is provided in Chapter 4.

Public awareness

Our Office uses many different tools to raise awareness of privacy among Canadians – speeches and other public presentations, media interviews, paper and online publications, an ever-changing website, social media such as Twitter and blogs, YouTube videos, contests for young people, educational kits for teachers and even a popular privacy calendar

Details of our public awareness activities can be found in Chapter section 5.

1.2 Supporting Parliament

From a legislative perspective, Parliament and its committees had a reduced sitting schedule during 2011 because of the general election. As well, with Parliamentary priorities focused mainly on public sector concerns such as crime and the federal budget, our Office was called upon for fewer PIPEDA-related appearances.

The general federal election of May 2, 2011, sent new members to the House of Commons for the third time since 2006. The Conservative Party remained in power, increasing their seats from a minority to a majority in the 41st Parliament.

While the government has focused largely on public sector-related bills, it also reintroduced Bill C-12, an Act to amend the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act. When the year ended, it was still at the beginning of the legislative process and had not been referred to a standing committee for review.

The Government also said it would introduce Internet surveillance legislation that did not pass in the previous Parliament. In this regard, we continued to express our concerns related to lawful access legislation.

Appearances Before MPs and Senators

During 2011, our Commissioner and Assistant Commissioner made five Parliamentary committee appearances.

The OPC also examined a total of 11 bills as well as two new committee studies introduced in the 41st Parliament for potential privacy implications. One was the E-Commerce in Canada study of the Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Technology.

Throughout the year, we also had many informal interactions with Parliamentarians, including follow-ups to committee appearances, subject-matter inquiries from Members of Parliament, face-to-face meetings and briefings.

PIPEDA-Related Parliamentary Work

Given the reduced sitting scheduled in 2011, the Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics postponed a review of our 2010 Annual Report to Parliament on PIPEDA.

1.3 Supporting Organizations

This past year we released a final report on our 2010 Consultations on Online Tracking, Profiling and Targeting, and Cloud Computing. The contributions and analysis associated with the consultations gave rise to several activities in 2011, including:

- guidelines to help organizations involved in online behavioural advertising ensure that their practices are fair, transparent and in compliance with PIPEDA; and

- continuing work to develop cloud computing guidance specifically directed to privacy issues relevant to Small- and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs). This guidance will be available early in 2012.

We also offered guidance to legal professionals in the private sector. PIPEDA and Your Practice — A Privacy Handbook for Lawyers, launched in August, explains how PIPEDA relates to the everyday practice of Canadian lawyers.

Our Office, along with the Offices of the Information and Privacy Commissioners of Alberta and British Columbia, jointly launched a new online tool to help businesses better safeguard the personal information of customers and employees. Securing Personal Information: A Self-Assessment Tool for Organizations is a detailed online questionnaire and analysis instrument that helps organizations gauge how well they are protecting personal information, in keeping with the applicable private sector privacy law.

The OPC Toronto office, established in 2010, undertook almost 50 outreach activities in 2011 to organizations and industry associations. These were part of our efforts to increase understanding of PIPEDA and compliance requirements by business.

Chapter 5 contains more details of these various initiatives.

1.4 Advancing Knowledge

Armchair Discussions

An OPC priority is helping Canadians better understand the diverse privacy issues that affect their lives and how they can protect their privacy.

In 2011, we organized a few armchair discussions to spotlight new and provocative voices exploring new perspectives on privacy research. We also asked each speaker for short papers exploring areas that interest them in the field of privacy.

In February 2011, we invited behavioural economist Alessandro Acquisti, associate professor of Information Technology and Public Policy at the Heinz College, Carnegie Mellon University, and sociologist Christena Nippert-Eng, associate professor of sociology in the College of Science and Letters at the Illinois Institute of Technology, to talk about what motivates us to reveal or conceal details of our personal lives, and how we protect the private lives of others around us.

In April, we invited tech innovators Adam Greenfield and Aza Raskin to explore opportunities for privacy ranging from the design of intimate devices, like smartphones, that we share our lives with every day, to the sensor-rich landscape around us. They discussed opportunities for companies to empower individuals with greater choice and control over how their data are used and the prospects for greater collaboration within and across industry sectors.

In June, we heard from Canada Research Chair David Murakami-Wood, associate professor in the Department of Sociology at Queen’s University, and Craig Forcese, associate professor in the Faculty of Law at the University of Ottawa, who both examined the privacy risks in a society that is increasingly placing its citizens under greater surveillance.

In September, we invited two experts on young people’s use of social media, Kate Raynes Goldie, Ph.D. candidate at the Department of Internet Studies at Curtin University of Technology, and Matthew Johnson, director of education with the Media Awareness Network, to talk about what privacy means to youth and how to help youth preserve their privacy by promoting digital literacy skills.

1.5 Global Initiatives

Enforcement Cooperation

In 1973, Sweden enacted the world’s first national privacy law. Four decades later, there are now roughly 80 national privacy laws, or data protection laws as they are often called, in force globally. Many have been passed since PIPEDA came into force on January 1, 2001.

Although differing significantly in terms of scope and enforcement, most of these laws are based on what are commonly referred to as “fair information principles.” These principles are set out in Schedule 1 of PIPEDA.

Sharing common principles allows privacy commissioners and data protection authorities to pursue common goals even if the wording of their legislation differs – PIPEDA’s “limiting collection” is “data minimization” in European law.

Not only do privacy enforcement authorities share the similar objectives of promoting the protection of personal information and furthering the rights of individuals, but they also face similar challenges.

Privacy issues are becoming global. Increasingly, individuals throughout the world rely on common information and communication technologies; they share information, videos and photos using a few highly popular social networking platforms; they play online games using the same platforms and they conduct searches using the same search engines. As a result, when one of these global companies changes its privacy practices, or worse, when it experiences a privacy breach (as we witnessed with Sony’s PlayStation Network in 2011), millions of people worldwide can be affected.

Global issues demand a global response. As a result of amendments to PIPEDA that came into force in 2011, our Office is in a much better position to cooperate with our foreign counterparts on issues that affect individuals in other jurisdictions.

We can now collaborate and share information with persons or bodies in a foreign state that have similar legislated functions and duties or with persons or bodies who have legislated responsibilities relating to conduct that would be a contravention of PIPEDA. By sharing our expertise and the information we obtain during our investigations, we can use our resources more effectively and conduct more thorough and efficient investigations.

Our ability to share information is subject to certain conditions, most notably a requirement for a written arrangement with the other party, which must contain confidentiality provisions limiting the use of any information we share or receive. Arrangements with both the Dutch and the Irish data privacy commissioners were being finalized at the end of 2011.

Our Office has also played a leadership role in encouraging cooperation more generally.

At the 33rd International Conference of Data Protection and Privacy Commissioners, held in Mexico City in November 2011, commissioners passed a resolution on increasing international enforcement coordination. Our Office is one of the co-chairs of a working group that was created to develop a framework and processes for possible coordinated enforcement actions.

The working group will build on the success of the Global Privacy Enforcement Network (GPEN) and the Cross-border Privacy Enforcement Arrangement (CPEA) of Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), which we described in our 2010 Annual Report.

Our Office was one of the founding members of GPEN, which now has more than 20 members.

We are also a member of the CPEA, which is limited to enforcement authorities in the Asia-Pacific region and now has members from six APEC economies.

As well, our Office is a member of the Asia Pacific Privacy Authorities (APPA) forum, made up of privacy authorities in the Asia Pacific region. APPA holds two meeting annually where we exchange ideas and best practices about privacy regulation, new technologies and ways to raise awareness of privacy issues.

Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD)

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Guidelines on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Data Flows were developed more than 30 years ago. Although the guidelines have proven remarkably resilient, the world has changed dramatically since then.

Recognizing this, the OECD has launched a review of the guidelines to assess whether they are still relevant considering the “changing technologies, markets and user behaviour and the growing importance of digital identities.” The review is being conducted by the OECD’s Working Party on Information Security and Privacy (WPISP) and it is being advised and supported by a multi-stakeholder volunteer group chaired by Commissioner Stoddart.

The volunteer group will be expected to make preliminary recommendations to the WPISP. The range of possible recommendations is wide. The WPISP could conclude that the technology-neutral guidelines are still as relevant as ever or it could conclude that parts of the guidelines need to be updated or revised.

Francophonie

Our Office was instrumental in the creation in 2007 of the organization representing francophone data protection authorities around the world, the Association francophone des autorités de protection des données personelles (AFAPDP). We are committed to helping the AFAPDP provide increased support to developing countries in the Francophonie as they establish new legislative frameworks to protect the privacy rights of their citizens.

In 2011, Assistant Commissioner Chantal Bernier attended the association’s first training seminar to take place on the African continent, in Dakar, Senegal. In her presentations, she discussed how privacy principles apply in various legal regimes and gave an overview of the historical importance of the OECD guidelines. In a second AFAPDP seminar, before the International Conference of Data Protection and Privacy Commissioners in Mexico, she focused on the accountability principle and its pratical application.

1.6 Technology Lab

Our tech lab and its small staff keep the OPC up-to-date with developing technologies and provide expert support for audits and investigations where technology is a major component. The technologies run the gamut from apps through smartphones to gaming consoles. Lab technologists can scrutinize such apps or devices to learn what personal information is being stored, what is being exchanged on the web and how it is being protected.

As an example of current privacy concerns, the lab has the ability to analyze the tracking techniques used by online behavioural advertisers and also the effectiveness of privacy controls on social networking sites.

Chapter 2

Key Issue: Children and Youth Privacy

Introduction

In the battle to preserve the value of privacy in an online world, children and youth increasingly find themselves in the front lines.

Young Canadians are the most open to adopting new communications technologies which can, in some cases, invade their privacy. This holds true, not surprisingly, for those aged 18 to 34, as confirmed by a national opinion survey carried out this year for the OPC. (See section 3.3)

But the true adoption age for digital media is much, much younger.

We know, for example, that thousands of apps targeted at babies and toddlers are now available to teach little ones the alphabet and to entertain them with nursery rhymes.

The evidence may still be mostly anecdotal, but one recent study found that a third of North American Gen-Y moms (those aged 18 to 27) have let their children use a laptop by age two.

By the time the kids are three, those laptops and tablets are connected to the Internet daily for about a quarter of U.S. kids, according to the Joan Ganz Center in New York. By age five, the proportion online has soared to half.

We are giving our children unprecedented access to the Internet, but what are we doing to teach them about how to protect their privacy in the online environment?

We often hear the claim that young people growing up in this digital era do not care about privacy. This is not true.

While concepts of privacy are evolving, and young people tend to think about privacy differently than their parents, study after study shows that young people do care about their privacy.

What we hear when we go out to speak in schools, is that young people want to protect their online reputations, but many of them just don’t know how. They ask us how to control who sees what is in their online profiles. They want to know how to block unwanted contact on social networking sites, and how to learn what others are posting about them.

There are a number of reasons why we see many younger Canadians running into privacy pitfalls online.

Part of the explanation is that they are such enthusiastic users of online technologies that they sometimes try new applications before all the privacy kinks have been identified and ironed out.

As well, young people tend to think that their online space is private and only their friends will see the content. They live in the moment and often don’t think about how the messages they send or post today could turn up to haunt them years in the future.

Teenagers growing up in an online world are being watched and analyzed like no other previous generation.

Many online players are trying to capture the eyeballs and keystrokes of the young, with a view to commercializing their personal information. Below, we relate the tale of a website which draws revenue from ads that target the 13-to-18-year-olds who make up one-third of its users.

Yet, while a lot of effort is going into exploiting the personal information of children and youth for profit, far fewer resources are being expended in helping children and youth recognize the value of privacy protection and develop the skills necessary to protect their personal information.

Children and youth face particular privacy perils because they lack the knowledge and experience to judge risk appropriately and mitigate it effectively.

As a result, our Office has substantially stepped up its efforts aimed at helping this vulnerable portion of Canadian society.

During the past year, we developed two new graphic-rich privacy packages for school and community use, a teen-oriented video and a tip sheet for parents. We continued a popular contest where teens produce short videos about privacy concerns. We continued to add resources to our youth website and blogs.

In addition, the OPC’s Contributions Program has recently funded three innovative research and public education initiatives that explored the relationship between youth and privacy and promoted the protection of personal information among youth.

But a much greater effort is needed.

A five-nation study of digital literacy by the Media Awareness Network (MNet) for the OPC concluded that, in Canada, online privacy does not receive the attention it deserves within digital literacy. And existing educational efforts are also hampered by a lack of coordinated strategy.

MNet’s nine specific recommendations, detailed in Chapter 2, include the idea of digital competencies for all Canadians, such as a knowledge of privacy rights and recourse mechanisms.

Here’s an idea: Why not award badges to young people who master such digital competencies, much like Girl Guides and Boy Scouts win badges?

Innovative thinking like that would also help parents struggling to improve their own digital literacy skills, while simultaneously trying to impart a whole new set of life skills to their children.

Understandably, some parents want to use new technologies to make sure their children are safe. But this can lead to video surveillance and GPS tracking which include little or no consideration for the privacy rights of children and youth.

That matters because, first and foremost, kids learn about the concept of privacy from how they see privacy practised at home.

Our survey of relevant research suggests that if children are brought up in a surveillance environment where privacy is not valued, then they could in turn learn to not value privacy. These children may also fail to learn how to establish their own privacy boundaries and be less likely to respect the boundaries of others.

Perhaps worse, constant surveillance can introduce the notion of distrust and dishonesty into family life, encouraging children to become secretive. If Mom might be watching the front door through an online video cam that’s part of a home security system, then her daughter could be tempted to sneak her boyfriend in by the back door.

At first blush, such speculation may seem far-fetched, even alarmist.

But privacy guru danah boyd of New York University and Microsoft has pointed out that teens have already evolved defences against parental monitoring of semi-public fora like Facebook.

The teens hide their candid messages to their friends in plain sight, says boyd, by using language and cultural references which carry special meanings for their friends but seem innocuous to adults.

Boyd gives an example of a teenage girl despondent over a romantic breakup. To hide her true feelings from her mother, the girl posted to Facebook the lyrics from Monty Python’s “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life.” Her mother responded with a note that she seemed to be happy.

But her friends knew differently since the song features in a movie where the characters are about to be killed. They immediately got in touch to ask how the girl was coping.

2.1 Investigations Relating to Children and Youth

Nexopia Investigation:

Website Aimed at Youth Tackles Some Privacy Problems but Not All

Significant privacy flaws uncovered during the OPC’s first investigation of a youth-oriented social networking site could serve as a lesson of what to avoid for websites that encourage the collection and publishing of personal information about youth.

The in-depth investigation of Nexopia identified several areas where the organization was in breach of PIPEDA and resulted in 24 recommendations. Many of the concerns could have been avoided if privacy issues had been more carefully considered when the website was developed.

Nexopia was open and cooperative during the investigation and the Commissioner was satisfied with the organization’s response to 20 recommendations. However, four recommendations related to the indefinite retention of the personal information remained unresolved at the end of 2011.

Background

Founded in 2003, Edmonton-based Nexopia predates many other popular social media websites. It claims more than 1.6 million registered users, with more than a third between the ages of 13 and 18. Roughly half the users are from Alberta and British Columbia.

Nexopia considers itself an “open community” website differing from sites like Facebook. Although 90 percent of its users are also Facebook users, Nexopia argues that on Facebook “they communicate and share with their real life friends,” while on Nexopia “they communicate with their online friends and ‘show off’ to the world.”

Commissioner Stoddart commented: “The fact that the site is targeted at younger people strongly influenced our approach in this investigation. Given that so many of Nexopia’s users are young, extra care is needed to ensure that they understand the site’s privacy practices.”

“Other websites targeted at younger people also need to take note of this investigation and ensure they’ve adequately considered the privacy considerations particular to a youth context.”

What We Found

Our investigation was prompted by a complaint by the Public Interest Advocacy Centre based in Ottawa. The key areas where Nexopia did not comply with PIPEDA included:

- default settings inappropriate for its target youth audience and a lack of clarity about available privacy settings;

- a lack of meaningful consent for the collection, use and disclosure of personal information collected at registration;

- the sharing of personal information with advertisers and other third parties without proper consent; and

- the indefinite retention of personal information.

Issues

- Disclosure of user profiles to the public and default privacy settings

At the beginning of our investigation, Nexopia’s default privacy settings were “visible to all” – meaning visible to the whole Internet.

Given the special circumstances surrounding youth users and privacy, the OPC found that a reasonable person would not consider it appropriate for Nexopia to pre-select settings that push users towards disclosing their personal information, in some cases very sensitive personal information, for potentially everyone on the Internet to see.

The investigation also revealed that Nexopia does not adequately notify its users of default settings, or explain the difference between various settings.

Our Office found more could be done to inform users about the available privacy settings to ensure that users can make informed decisions about how they can control access to their personal information.

Nexopia users should be expected to opt-in to the “visible to all” setting – and with a full understanding of the implications of that choice.

Our Office found that more restrictive default settings, coupled with increased information for users in a format appropriate for a youth audience, would strike an appropriate balance between ensuring young people can enjoy the benefits of social networking, while protecting their privacy.

The OPC was satisfied that Nexopia’s proposed corrective measures, which include changing defaults and providing better information to users, will meet our recommendations.

- Lack of meaningful consent for the collection, use and disclosure of personal information collected at registration

Our investigation found that Nexopia failed to adequately identify and inform users of its purposes for the collection, use and disclosure of the personal information it requires users to provide at registration.

For example, it was not clear which “core” profile information and profile pictures would be visible to users within the Nexopia community and anyone on the Internet, by default.

Nexopia acknowledged that the current version of its Privacy Policy was not necessarily written with the needs of youth in mind.

Nexopia was passively relying on users to read and agree to the terms of its lengthy and formal Privacy Policy as a means of obtaining consent. Our Office found that a mere link to the policy at the bottom of the registration page was not sufficient to obtain appropriate consent from the site’s target youth audience.

The OPC was pleased that Nexopia has agreed to update its Privacy Policy to add information and also use language appropriate to its user base. It will also require users to review its Privacy Policy as part of the registration process – although our Office has encouraged Nexopia to explore ways to present privacy information in more innovative ways.

- Sharing of personal information with advertisers without proper consent

The information Nexopia provides to users about its advertising practices, particularly regarding the sharing of personal information with advertisers was incomplete. In some cases, they were sharing personal information without telling users clearly.

For example, Nexopia did not fully explain what targeted advertising is and how such advertising works. As well, its Privacy Policy did not explain that Nexopia allows third parties, such as advertising networks, to place cookies in the browsers of users and visitors to its site in order to collect information about web usage.

The OPC was of the view that Nexopia’s own use of personal information for advertising purposes and its serving of behaviourally targeted advertisements to users is acceptable as a condition of service, provided individuals are made fully aware of how this practice works.

However, our Office was also of the opinion that individuals should be able to opt-out of being tracked by third parties – which are typically unknown to them.

Nexopia agreed to provide more information in its privacy policy and on its website about targeted advertising and the presence of third-party served advertising and tracking cookies. These changes were to include links to information about advertising and cookies on the site – and also about how cookies work and how they can be removed.

The OPC was satisfied with Nexopia’s response to our concerns.

- Sharing of personal information with other third parties without proper consent

Nexopia regularly disclosed users’ unique user IDs to a payment processor when users make purchases on the site. As well, it disclosed a user’s age, gender and unique user ID to a rewards company each time a user participates in what the site calls “Earn Plus” offers.

The site did not explain to users the potential disclosure of their personal information to the rewards company, nor that such disclosures may be provided over and above any information the user provides directly to the rewards company as a condition of a particular “Earn Plus” offer. Nexopia admitted that their online statements and actual disclosure practices had become misleading.

Nexopia asserted that the information provided to the payment processor and the rewards company could not be used to identify and obtain more information about individual users. However, our testing revealed that a user’s unique ID can be used to link to the user’s profile and potentially permit access to all the personal information displayed there.

In our view, Nexopia could use another unique code or identifying number that limits the amount of personal information that passes between the parties and yet still allows efficient billing and payment processing.

Nexopia agreed to stop providing unique user IDs to the payment processor and has made the decision to completely remove the “Earn Plus” service from the site, and, therefore, will stop sharing users’ personal information with the rewards company.

The OPC was satisfied with Nexopia’s response.

- Retention of personal information

Nexopia collected non-users’ email addresses through invitations to join the site initiated by users. Users were not required to confirm to Nexopia that they had their friend’s consent for the purposes of sending an invitation to join the website, prior to providing the friend’s email address to the company.

A non-user who didn’t want to receive further invitations could click on a link to a page entitled “Opt out of Nexopia.com invites”.

However, the non-user was not informed on this page that their email address would be retained by Nexopia. For the unsubscribe feature to be effective, Nexopia said it must retain for an indefinite period a list of email addresses to which no further messages would be sent.

In our view, it was important for the user who provides the email address in the first place to ensure that they have obtained prior consent from the email address owner, their friend, for the invitation email to be issued by Nexopia.

As well, our Office recommended that Nexopia offer non-users a clear choice between a) unsubscribing from join-the-site invitation emails, or b) permanent deletion of their email address.

The OPC was satisfied with Nexopia’s response to our concerns about this issue.

Nexopia agreed to add text to its “Find and Add Friends” feature to emphasize that users should have non-users’ permission to give the website their email addresses.

The organization also agreed that, in the future, non-users who receive invitation emails will be able to request the permanent deletion of their email address from Nexopia’s database.

Our Office also considered the issue of deletion of accounts.

When users clicked on an option called “Delete Account” they were advised: This will delete your account, including your profile, your pictures, friends list, messages, etc. Your forum posts, comments and messages in other users’ inboxes will remain.

In fact, Nexopia advised us that the only information deleted is the user’s “shouts”.

Other information was stored indefinitely. (For example, username; user ID; email address; IP address and log-in information; friends list; gallery pictures; profile contents; messages and comments; and profile photos.)

Another concern related to account deactivation and the freezing of accounts, either by Nexopia or upon request by a user. The personal information contained in frozen user accounts remained inactive on Nexopia’s servers indefinitely and was not subject to any periodic review.

Nexopia admitted it had not deleted account information since 2004, either from “deleted” or frozen accounts.

It was clearly misleading to provide a “Delete Account” option. The OPC recommended that Nexopia provide a true delete option for the accounts and personal information of users.

Unfortunately, Nexopia said it would not implement this recommendation because the cost of doing so would be prohibitively high. It also argued that the information stored in the archives was only accessible to system administrators and recovered in the event that they received a warrant from a law enforcement authority.

The OPC understood the technical challenges presented in permanently deleting users’ personal information. However, Nexopia’s practice of storing indefinitely all of an individual’s personal information was in contravention of PIPEDA.

It’s clear that law enforcement authorities sometimes require access to information. Such requests or warrants may justify a longer retention period in specific cases, but they do not justify wholesale and indefinite retention of all records just in case there may be a request at some point in time.

Nexopia’s practice of storing personal information in its archives indefinitely, on the small possibility it may be the subject of a warrant from a law enforcement agency, was therefore not acceptable.

Moreover, there are security risks inherent in retaining vast amounts of former users’ personal information, long after it has served its original purpose. As well, our Office is concerned that Nexopia’s users are being misled into thinking they can delete their personal information at some point, if they want to.

This issue remained unresolved at the end of our investigation. The OPC is proceeding to address these unresolved issues in accordance with our authorities under PIPEDA, which include the option of going to Federal Court to seek to have the recommendations enforced.

The full investigation report is available on our website.

Daycare Centre Modified Webcam Monitoring to Increase Privacy Protection

Background

The complainant enrolled his son at a private daycare centre and was told that parents could pay a fee for its webcam service to let them see their child’s daycareroom in real time. Parents viewed the webcam feed via the Internet after entering a unique password.

The daycare centre stated that it had instituted the webcam service for two reasons: first, so it could monitor the daycare environment for security purposes; and, second, to provide parents with assurances regarding the daycare environment.

The centre told the OPC that approximately 60 percent of the parents of registered children had enrolled in the webcam service.

The complainant subsequently learned that the webcam feed was being recorded. He notified the daycare centre that he objected to the recording and that he felt appropriate privacy safeguards were not in place.

Following notification of the investigation, the centre deleted its saved video files and modified its systems to no longer record the video stream captured by its webcam. The centre also implemented a privacy policy requiring all parents to sign a form consenting to the webcam monitoring, regardless of whether a parent wished to enrol in the service.

The daycare centre acknowledged that a parent would be able to record and send out the webcam feed as viewed on a personal computer. Upon our Office’s suggestion, the centre required parents using the webcam service to sign a contract agreeing to not record the webcam feed and promising to keep the assigned password confidential.

What We Found

At issue was whether the daycare centre collected the complainant’s son’s personal information without consent and failed to adequately safeguard his son’s personal information.

Initially, the OPC was of the view that the daycare centre was not in compliance with PIPEDA Principles 4.7 (security) and 4.3 (consent) and subsection 5(3) (appropriate purposes) and recommended the centre cease the webcam monitoring program.

During the investigation, however, the centre improved its organizational and technological security measures by ceasing to record the video stream, implementing a privacy policy and enhancing password protection features. Nonetheless, our Office recommended that the daycare centre further enhance its technological security measures and implement additional contractual terms in order to prevent inappropriate use of the information collected by the webcam.

Consultation with the Ministry of Children and Youth Services in Ontario at the time revealed that of the 4,784 licensed child care programs operating in Ontario, only 61 offered live video streaming – and several daycares without webcam monitoring operated close to the complainant’s home. Because individuals appear to have alternative child care options, there was no evidence that parental consent was not voluntary.

Conclusion

The daycare centre indicated that it implemented all of our Office’s recommendations and we concluded that the complaint was resolved.

2.2 Surveillance of Children

After the OPC dealt with the above complaint, our Office determined it would be helpful to explore related issues further and conducted research about the effects of surveillance on children.

We conducted a literature review to identify and analyze research which addressed the effects that current surveillance practices have on children, including video surveillance, online monitoring and the use of biometrics.

We focused on surveillance in Canada and in societies similar to ours. Despite the paucity of pertinent research, there was consensus among the work that does exist that constant surveillance in the long term affects how children view and interact with the world.

All of the research noted the prevalence of surveillance in children’s lives today. There are parents using video baby monitors and “nanny cams,” and later Internet and cell phone monitoring software and GPS. Schools have security cameras, RFID tracking, and palm scanners. Corporations track kids online for marketing purposes.

Surveillance has become the new norm for several reasons. Parents are frightened by over-blown stories of “stranger danger” (which statistics do not support), and surveillance is affordable, available and easy to use.

As well, they see that the state uses surveillance to detect and deter anti-social behaviour, while business uses online surveillance for commercial profit.

According to the available research, indiscriminate surveillance on children without proper boundaries and explanations may potentially affect:

- Autonomy and social development.

Without the freedom to experiment with making critical and ethical choices, children could instead make decisions based on fear and risk of punishment. They could become less likely to learn to regulate and direct their own behaviour. - Trust, fear and learning to assess risk.

Surveillance could create an artificial, risk-free environment where children might not be given opportunities to develop self confidence and risk management skills. - Digital literacy.

Monitoring software could hamper children’s development of digital literacy skills needed to navigate the online world effectively. - Understanding privacy.

If children are brought up in a surveillance environment where privacy is not valued, they in turn may not value privacy. These children may also not learn how to establish their own privacy boundaries and will be less likely to respect the boundaries of others.

2.3 Youth Outreach Initiatives

We have successfully launched two youth presentation packages intended to be used with students in Grades 7-8 and Grades 9-12Footnote 1

The goal is to show young people how technology can affect their privacy, and how they can build secure online identities while keeping their personal information safe.

Each package includes a set of vibrant PowerPoint slides with accompanying speaking notes to assist teachers or other adults in providing effective and engaging presentations in schools or the community. Presentations take about 30 minutes, but extra time for group discussion is encouraged.

Presenters are invited to provide feedback to the OPC so the package can be continually improved.

We have also developed a four-and-a-half-minute video, What Can YOU Do to Protect Your Online Rep, which speaks to teens directly and covers the key privacy concepts that young people need to consider when sharing information online. The video – launched in January 2012 – can be viewed online or downloaded for discussing privacy issues with teens.

The Office also developed a tip sheet geared to parents who want to talk to their kids about privacy in the online world. The tips urge parents to try out the online spaces their kids are using, keep up with the technology, emphasize the importance of password protection and tell their kids to “think before they click.”

Our third annual my privacy & me national video contest again proved popular, with more than 100 entries. The winning videos were submitted by students from across Canada.

Students aged 12 to 18 enter by producing video public service announcements from one to two minutes long on timely privacy issues.

A fourth contest was launched in September, with winning entries expected to be announced in March 2012.

Further details on all these initiatives can be found on our special youth website, www.youthprivacy.ca.

2.4 Digital Literacy

Digital literacy includes the abilities to use, understand and create with computers and the Internet. Unlike Australia and the U.K., Canada does not have a national strategy for digital literacy.

The development of digital literacy skills was included in the federal government’s Digital Economy Strategy Consultation process in May 2010, but it has not received attention in the follow-up.

To better understand the state of play, we contracted the Media Awareness Network (MNet) to identify leading digital literacy initiatives in Canada and abroad; evaluate their privacy component; and identify opportunities within digital literacy initiatives for our Office to raise the online privacy awareness and skills of Canadians.

MNet found that although the importance of digital literacy is recognized in Canada, online privacy as a specific topic within digital literacy does not receive the attention it deserves and existing efforts are hampered by a lack of coordinated strategy.

In its paper, MNet compared Canadian digital literacy programs with efforts from the U.K., the U.S., Australia and Brazil. It found the following trends:

- Youth are a prime target for digital literacy interventions, including privacy skills. Although adults are also vulnerable to privacy risks, they are made a lower priority for digital literacy skills development.

- Current digital literacy interventions do not anticipate future risks but rather scramble to keep up with the present.

- Outside of broadly defined groups such as youth, adults and seniors, existing programs display little sensitivity to other factors which may affect digital literacy, such as immigrant status or gender.

- Despite the possibility of delivering digital literacy education exclusively online, all the countries studied prefer face-to-face instruction, especially for seniors.

Based on its review, MNet made the following recommendations:

- Define privacy competencies that Canadians need to manage their personal information online. The suggested competencies range from awareness that personal information is increasingly treated as a commodity to a knowledge of privacy rights and recourse mechanisms.

- Promote these privacy competencies as an entitlement for Canadians.

- Integrate issues of data protection and democracy in educational modules.

- Focus more on adults.

- Support continuing digital literacy education for all elementary and secondary students.

- Prepare privacy resources which can be adapted to many audiences.

- Support Community Access Program sites as venues for privacy education.

- Promote and support existing, high-quality resources.

- Promote a national focus on digital literacy.

2.5 Contributions Program – Projects for Youth

Over the past few years, the OPC’s Contributions Program has funded innovative research and public education initiatives that explored the relationship between youth and privacy and promoted the protection of personal information among youth. For instance:

- The Media Awareness Network was awarded funding in 2011-12 for its project Young Canadians in a Wired World - Phase III. This project is one of the most comprehensive and wide-ranging studies of Internet use by children and teens in Canada. Phase III of the project covers completion of qualitative research previously undertaken by MNet using parent and youth focus groups in Calgary, Toronto and Montreal, writing of the qualitative research final report, and developing and implementing a communications strategy.

- Also in 2011-12, Atmosphere Industries was awarded funding for its project Gaming Privacy: Creating a Privacy Game with Canadian Children. This project proposes to work with Canadian children to create, deploy and research a cross-media game that engages children ages eight and up in the development of privacy literacy skills. Cross-media games mix physical with digital spaces and technologies to create unique experiences that get people working together in public spaces to solve puzzles and accomplish game goals.

- In 2009-10, OPC funded a project carried out by the University of Guelph, titled Privacy and Disclosure on Facebook: Youth & Adults’ Information Disclosure and Perceptions of Privacy Risks. It aimed to advance the understanding of information sharing on Facebook by high school students and working adults through a literature review and a survey of 600 Canadians. The research focused on factors that motivated disclosure of information and the use of privacy settings as well as examining Facebook users' perception of privacy risks and knowledge of privacy settings. The final report includes recommendations to help the OPC develop strategies for making the public aware of the privacy risks of social networking sites and the need to make more informed decisions about information sharing.

The OPC looks forward to the results of this research being applied and put to good use by interested end-users focusing on the identification and privacy needs of youth as they navigate the modern challenges of the online world.

Chapter 3

The Privacy Landscape

An overview of some of the other major issues addressed by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada during the year

The privacy landscape in 2011 featured both gradual evolutions and abrupt shifts, akin to the steady creep of the Earth’s crust punctuated with rare tectonic upheavals.

Once again, the principle-based structure of PIPEDA proved flexible and forceful enough to deal with the bulk of these privacy challenges. Yet the legislation itself is also evolving and further legislative changes may be needed to respond to emerging privacy challenges that differ in scope or nature from anything encountered in the 10-year life of the legislation.

During the year, the Commissioner suggested that the prospect of large penalties appeared necessary to convince companies to get serious about preventing data breaches. She also released an open letter calling on the federal government to justify its proposed “lawful access” legislation which had “serious repercussions for privacy rights.”

Canadians appear to recognize these emerging challenges. A public opinion poll commissioned by our Office found significantly more privacy concerns about new communications technologies than just two years ago.

Four in 10 of the 2,000 randomly polled Canadians said that computers and the Internet pose a risk to their privacy, up from one-quarter in a 2009 survey. Privacy concern also rose over online social networking sites, cell phones and online financial services.

As demonstrated by summaries of some of our investigations in this chapter, such concerns are often well founded.

In the field of financial privacy, for example, we found PIPEDA violations by an insurance company, a credit bureau, a car manufacturer and a credit union.

New concerns also surfaced regarding social networking giant Facebook, which has been featured in past reports. And we continue to monitor Google’s implementation of privacy improvements which we recommended after the company’s inappropriate collection of personal information.

To keep pace with the rapidly evolving privacy landscape, our Office issued guidance documents about biometrics and online behavioural advertising – two developments spawned by new technology. We also strengthened our technological expertise, partly to support OPC’s role in Canada’s new anti-spam legislation, which is expected to go into effect this year.

All these developments are detailed on the following pages, which examine some of the major issues we addressed during 2011.

3.1 Financial Privacy

Most people guard the details of their finances as zealously as they guard their PINs at the sales register or ATM. A nightmare shared by everyone would be learning that some crook is running amok with your credit card.

Because of such sensitivity and the huge number of transactions with Canadians, the financial sector has regularly accounted for the largest proportion of formal complaints accepted by the OPC. In 2012, it also gave rise to several noteworthy investigations, which are summarized here.

Investigations

Credit Bureau Purges Loan History from Individual’s Credit Report without his Knowledge

Background

An individual financed the purchase of a used vehicle through a third-party financing company. In financing the purchase of his vehicle, the complainant sought a lender that reported to a national credit bureau. He did so in the belief that a positive repayment history might help augment his overall credit standing.

The complainant began repaying his car loan in July 2004. By June 2008, the complainant’s loan was paid in full.

In 2008, following the repayment of his car loan, the complainant sought to take advantage of a provincial program which provided grants to qualified applicants towards the purchase of a home. The complainant appeared to have obtained a mortgage pre-approval from a mortgage broker conditional upon qualification for the grant.

According to the complainant, after receiving notice of acceptance for the grant, he returned to the mortgage broker with whom he had been conditionally pre-approved, only to be advised that he no longer qualified for the loan.

Although the reasons supporting the complainant’s denial of credit could not be determined with certainty – lenders and financial institutions having a right to their own criteria for loan approval – the mortgage broker in question informed our Office that credit information relating to the complainant’s car loan with the financier was not listed on the complainant’s credit history.

It was the mortgage broker’s belief that the absence of the car loan history may have harmed the complainant’s credit score. In the broker’s view, the complainant’s loan with the financier, which showed a generally positive repayment history, might have helped in part to re-establish the complainant’s credit rating. It was his understanding that the complainant’s credit score had dropped significantly from the time when the complainant had been pre-approved for a mortgage, to the time when the complainant had qualified for the grant.

What We Found

While we were unable to estimate how much the complainant’s credit score may have been altered by the loss of car loan information, our investigation corroborated the fact that car loan information related to the financier, once listed on the complainant’s credit report, was later missing.

Investigation revealed that the financier had previously been reporting the complainant’s payment history to a credit bureau on a monthly basis. But some time before settlement of the complainant’s loan, the financier ceased reporting to that credit bureau.

According to the credit bureau, it was the company’s policy to stop reporting any information from a data source with which it did not have an ongoing relationship (i.e., “a severed data source”) approximately 60 days after its relationship with a data source ended. This policy effectively purged all information associated with a severed data source – whether positive or negative – leaving no trace of that particular credit history on an individual’s file. The credit bureau asserts this policy was necessary to ensure that information provided in its credit reports remained accurate, complete and up-to-date.

Our investigation focused primarily on the credit bureau’s obligations to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the complainant’s credit file. We also considered matters relating to openness. To this end, we closely reviewed the credit bureau’s policies and practices surrounding severed data sources, taking into account the company’s obligations under provincial credit reporting and consumer protection acts.

Despite our initial misgivings about the deletion of the complainant’s credit history, over the course of our investigation the credit bureau produced sufficient evidence to demonstrate how reporting information from a severed data source might adversely affect the integrity of its credit reports. Although the effects in this case of the purging of loan information from the complainant’s credit report were such that it rendered his credit history incomplete, we could envision just as many other scenarios in which not purging information from a severed data source might have led to an equally inaccurate or incomplete credit picture.

Without continuity in the reporting relationship with a data source, the credit bureau was unable to ensure that the information in its credit reports was recent, reliable and up-to-date. Not only would the credit bureau have been unable to report on subsequent changes to an individual’s credit report, the company would also have been unable to verify and investigate inaccuracies in data reporting.

Despite the above, we were still concerned that credit information was entirely purged from the complainant’s credit file, without his knowledge. In this case, not only was the complainant completely unaware that his personal information was to be deleted, but third parties who might have relied on the company’s credit reports for lending appeared to have been similarly unaware of the company’s policies and practices.

At the time of our investigation, the credit bureau did not publicly disclose its 60-day retention policy for information from severed data sources. The company’s data retention policy stated only that: “A credit transaction will automatically purge from the system six years from the date of last activity.”

Had the complainant been aware of the credit bureau’s 60-day policy, he may have been in a better position to monitor his file and to consider placing a narrative on his credit report. He might also have thought to take action to obtain information directly from the severed data source in a timely manner in order to supplement his credit record.

Conclusion

As PIPEDA requires that an organization make readily available to individuals specific information about its policies and practices relating to the management of personal information, and so far as the credit bureau failed to be open with the complainant about its policy on severed data sources, we found the complaint to be well founded. The credit bureau agreed to implement our Office’s recommendations to address this issue.

Bank Properly Redacted Information Related to Credit Card Fraud Probe

The complainant alleged that a bank denied her access to her personal information relating to the bank’s investigation into the alleged fraudulent use of her credit card.

The respondent bank had informed the complainant that her credit card would be cancelled because of potential fraudulent use of the card. After more than six months dealing with the customer care centre and ombudsman’s office of the bank, the complainant made an access request to the bank’s privacy officer asking for all documents pertaining to the fraudulent use of her credit card and the ensuing cancellation. She specifically requested the name of the merchant where the alleged fraud occurred.

The bank provided five pages of documents about the credit card account but blacked out the names of some individuals and some of the computer commands used at the bank. Dissatisfied with this information, the individual filed an access complaint under PIPEDA against the bank.

Our Office found that the respondent bank properly redacted the personal information of other individuals, the computer system commands used during the investigation, and the information generated by the investigation into the alleged fraud.

We also found that the information redacted could be described as confidential commercial information. We agree that if the information redacted were to be released, the commercial interests of the respondent would suffer irreparable harm. The disclosure would be a breach of the respondent’s contractual obligations of confidentiality and, further, it could put at risk merchants with which the bank had contractual confidentiality obligations.

Our Office concluded that the complaint was not well founded.

Credit Union Should Have Obtained Consent for Credit Check on Spouse

An individual complained that a credit union had collected his personal information during what he alleged was a misleading credit application process. He also alleged that his personal information was kept without consent and that the credit union refused to destroy that information. Finally, he complained that the organization had conducted a credit check on his spouse without consent and had improperly used and disclosed the information acquired.

Our Office found that the respondent did make it clear to the complainant what personal information was required for the application process. We also took in consideration the legal obligation cited by the credit union to retain the complainant’s personal information.

However, the investigation raised concerns about the collection of information about the complainant’s spouse. Although the complainant’s spouse was named on the application form, she had not provided consent for a credit check.

Our Office recommended that the credit union revise its processes to ensure that consent is obtained from each customer applying for credit before obtaining a joint credit bureau report. The credit union confirmed that it had reinforced the procedure manual to make obtaining consent from both consumers a mandatory requirement before a joint credit bureau report is obtained.

Our Office concluded the complaints relating to both collection and consent with regard to the complainant’s personal information were not well founded.

Regarding the retention issue, we were satisfied that the legal obligation cited by the credit union for the retention of the complainant’s personal information for a period of seven years was reasonable. Accordingly, we concluded that the complaint was not well founded.

The complaints relating to consent to the collection of his spouse’s personal information and the use and disclosure of her information were well founded and resolved.

Task Force for the Payments System Review

The modern payments system extends all the way from cash purchases at a convenience store to multi-million dollar transfers between businesses. It includes all the institutions, instruments and services that support the transfer of value between parties, including money, financial instruments, and even the exchange of information.

That landscape is being dramatically altered by advances in the digital economy, which have facilitated an online marketplace where payments are being made in new and innovative ways.