Response to the OPC’s Consultation on Online Reputation

Timothy M. Banks, Liane Fong and Karl Schober

August 2016

Note: This submission was contributed by the author(s) to the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada’s Consultation on Online Reputation.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this document are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada.

Summary

The submission reviews the tools provided by social sharing platforms to manage online reputation, and examines the role that these platforms play in exercising a gatekeeper function that controls how reputations are shaped online. The authors examined 38 websites, including social media, dating, alternative news media, crowd-sourced news and internet service provider websites that contain functions that facilitate social interactions. The focus was to consider how these sites used community standards and takedown policies to balance rights of freedom of expression with other values, and how takedown tools may affect the ability of an individual to protect his or her online reputation.

In many cases, the authors found that there was a correlation between the strength of the takedown policy and the potential legal exposure of the platform. In addition, the authors noted:

Copyright: Almost all sites had clear mechanisms to assert copyright infringement if the individual’s own information, such as their photo, was being reproduced without his or her consent. Canada’s copyright law appears to be much less effective than its U.S. counterpart. Copyright law may have its limits due to numerous exceptions to copyright infringement based on fair use and fair dealing.

Age Limitations and Rights to Erasure: Generally, children’s sites did not contain an age restriction. The general inability for minors to enter into legally binding agreements means that there is a greater argument that takedown requests by minors of information that they have posted or that others have taken from them and reposted must be honoured.

Anonymity: Most sites permitted users to contribute content anonymously. There is a lack of social consensus on the right to use social functions anonymously. Anonymity complicates an individual’s ability to seek redress for defamation.

Bullying & Harassment: Majority of sites expressly prohibited bullying and harassment. Freedom of speech and anti-bullying / harassment are not incompatible with one another. Sites may have a role and responsibility as forms of vicarious liability develop in the future.

Pornography & Nudity: Prohibition of pornography and nudity is mixed. Sites may need to improve their takedown policies and procedures to avoid knowingly (or recklessly) publishing intimate images on their platforms when the person depicted in the image states that they did not consent.

Privacy: The majority of sites reviewed prohibit users from violating the privacy rights of others; however, the transparency and legal accountability for personal information on a commercial platform may require greater detail and obligations.

Takedown Procedures: The majority of sites had takedown procedures for code of conduct violations but the ease of use and whether they are efficient varied.

Overall, the authors concluded that social sharing platforms can assist in balancing online reputational rights and other values. However, at present, they are not sufficient.

Full Submission:

Note: As this submission was provided by an entity not subject to the Official Languages Act, the full document is only available in the language provided

Introduction

The mother of a child with a rare genetic disorder posted a photo of her son on her personal blog. The photo took on an unintended new life after it was lifted and turned into a viral internet meme comparing the son to a pug. The context of the photo was so entirely lost that some people appeared to believe the photo had been altered. The child was a prop for garish humour. The mother was reduced to chasing down social media sites to request the removal of the meme to limit the harmful messages about her defenseless son.Footnote 1

It seems undeniable that, in the online world, the intentional or unintentional dissemination of personal information can occur at startling speed and in a format that allows meaning to be easily transformed as the information is quickly detached from its original context. Sophisticated search engines, open governments and open courts means that the protection of “privacy via obscurity”Footnote 2 becomes quickly eroded. The breakneck speed at which personal information is spread, transformed and then cannot be retrieved amplifies reputational risks.

At least in Europe, Canada and the United States, active management of one’s reputation online may be on the cusp of being a necessary part of participation in social activities — whether online or not. And yet, we have to be cautious to recognize that the assertion of a right to “curate” our reputation is fundamentally a normative statement, which must be subjected to examination and not treated as an inviolable truth.

In other words, there is an ever-present danger of cultural-centrism when discussing “reputation”. We must recognize the individualist ideology underlying the assertion that an individual is entitled to “curate” his or her reputation even if that means editing history so that the individual is cast in the best possible light. Inventing and prioritizing a right of an individual to control the dissemination of his or her personal information over all other rights is a political choice about competing social values. The salutary effects of such a right must be balanced against other social values. At the same time, we must also be careful not to underestimate how institutions and technologies can be used by social mobs to oppress others or to voyeuristically to take pleasure in the humiliation of others. This tension can be seen in the OPC’s Report of Findings relating to Globe24h.Footnote 3 The open court principle which is rooted in the fundamental value that the decisions of the judicial and administrative branches of the state should be open to scrutiny was, in the eyes of some, perverted into a tool to subject the litigants to ongoing humiliation out of proportion to the purposes for which the original judicial and administrative decisions were made public.

Therefore, even as we must be vigilant against reactive attempts to fetish a right to erasure, we must equally be vigilant not to fetish a right to freedom of speech. Surely the bedrock of our democracy does not depend on the right to call a child a pug (as in the scenario that opened our introduction). And it doesn’t. There are existing remedies from copyright claims (for misappropriated photos) to defamation claims (for likening someone to a dog) to other means by which we have, for centuries, subjected freedom of speech to responsible limits.

Nevertheless, there are undeniable differences introduced by the ability to “self-publish” and distribute material via the Internet. Our submission reviews the tools provided by social sharing platforms to manage online reputation, and examines the role that these platforms play in exercising a gatekeeper function that controls how reputations are shaped online.

Authors’ qualification

We are pleased to make this submission to the OPC in response to its Consultation on Online Reputation. The submission is intended to contribute to public debate. However, a qualification is required. The authors are lawyers in private practice and working in the public sector. Timothy M. Banks is a privacy and advertising lawyer at a global law firm and acts primarily for international private sector organizations. Liane Fong is a lawyer that works in the public sector in government relations, issues management, and policy. Karl Schober is a privacy, advertising and competition lawyer practicing at a global law firm and acts primarily for private sector organizations. The authors emphasize that they make this submission solely on their own behalf to contribute to discussion, and not on behalf of their employers or clients. This submission is the result of an extended discussion among the authors and may not, in its totality, reflect the views of any individual author. Moreover, the authors are open-minded, and may change their views in the future.

The right to curate a reputation

Reputation is traditionally thought of as a normative belief held by a community about a person and based on available information about that person. Reputation is formed through the actual, perceived and imagined words, deeds, and characteristics of the individual and a community. Concepts of “personal brand” emphasize the ability (possibly illusory) of the individual to control and shape how the words, deeds and characteristics of the individual are perceived and evaluated by the community.

A common view is that reputation is a type of intangible good; something that is earned by an individual through efforts invested at building a positive reputation in a community.Footnote 4 Where narratives of self can be cultivated, reputation is the foundation of a personal brand. As with corporate brands, it is a form of goodwill, with a value associated with the individual worth being protected. The importance of protecting reputation can also be rooted in a theory of human dignity. Dissemination of untrue and damaging facts about an individual should be able to be countered using the law, such as through defamation suits.Footnote 5

However, while individuals can aim to restrict or control the information about them in an effort to control their reputation, reputation is ultimately formed externally; a projection of identity that that is shaped by others and through their interpretation of the information they receive about an individual. If reputation is an intangible good, is it one that is enjoyed by an individual as a result of one’s deeds and social interactions, or one that is owned and which one has the right to control? The former seems a more compelling explanation.

Identity and reputation is inherently a slippery notion. As author Daniel J. Solove highlights, the truth about a person is not a simple thing. Knowing certain information can distort judgment of another person rather than increase its accuracy. It is rare that we have the “whole story”.Footnote 6 Snippets of information taken out of context can stand in place to represent the whole.Footnote 7 Also, presentations of identity are a performance of self that inevitably leads to a level of curation. Or, in some cases, it may be outright staged. Consider how easily a performance artist can curate the image of herself as a Los Angeles party girl in her personal Instagram account, later revealed to be an art piece constructed to examine the performance of femininity.Footnote 8

Takedown policies as a tool for reputation management

If reputation is something that is shaped by external viewpoints, now that the Internet can unexpectedly shine a spotlight on an average individual, active management of one’s “personal brand” seems to demand a level of maintenance and cultivation approaching that normally afforded only for corporate brands.

In the OPC’s Consultation Paper, the OPC observed that many organizations have voluntary takedown policies, which have been extended to a wider range of conduct in response to the growing problem of online abuse. We were intrigued by this statement. Why are takedown policies viewed as “voluntary”? What substantive rights underlie the categories of conduct that are dealt with in existing takedown policies? Is there room for improvement? These are the questions that this submission engages with.

Overview of what we found

We examined 38 websites to determine whether those sites had takedown policies.Footnote 9 In particular, we reviewed websites to examine whether the use of takedown policies was widespread, what types of issues were covered by the takedown policies, whether there were any differences in approach between Canada and the United States, and whether the issues addressed in the takedown policies could be linked back to legal rights.

We found:

- Copyright: With one exception, all sites had clear mechanisms to assert copyright infringement if the individual's original photo (e.g. a selfie) was being reproduced without his or her permission. In the vast majority of these situations, a Digital Millennium Copyright Act (“DMCA”) notice-and-takedown policy was offered. However, it is not clear how successful these tools are for removing materials. Canadian copyright law appears to be much less effective as a tool than the DCMA. More information from the platforms is required. In addition, we have some concerns that copyright law may have limited utility because of the numerous exceptions to copyright infringement based on fair use and fair dealing.

- Age Limitations: The general inability for minors to enter into legally binding agreements means that there is a greater argument that takedown requests by minors of information that they have posted or that others have taken from them and reposted must be honoured. It is much more likely than not that there is no enforceable licence that would permit the use of the material. This is an area that should be the subject of much greater consideration. If there is room for legislative development, it would seem that a law relating to erasure rights for minors would be incremental to existing common law protections for minors.

- Anonymity: The majority of the sites permitted users to post material anonymously. We did not find any correlation between the sites that allowed for anonymous posting and those that had robust takedown or moderation policies. It appears that there remains no social consensus on the right to use social functions anonymously. However, it is clear that anonymous posting complicates an individual's ability to seek redress for defamation unless the platform is prepared to assist or is compelled to do so through judicial proceedings.

- Bullying & Harassment: The majority of sites expressly prohibited bullying and harassment. We were surprised, however, that sites where freedom of speech might be expected to be valued over other rights appeared to have the strongest anti-bullying and harassment provisions. By contrast, some social media sites appeared to provide more latitude to trolls and mob mentality. It remains to be seen whether the recognition of some form of vicarious liability might emerge that would push organizations into action. What does seem clear is that freedom of expression and anti-bullying / harassment are not incompatible with one another, even though early attempts to legislate in this area have failed for not striking the right balance.

- Pornography & Nudity: While many sites prohibited pornography and nudity, many did not. Those that did not have restrictions did not expressly warn individuals that they were required to ensure that the individual depicted in the picture consented to the photo being distributed (or even a reasonable belief). Organizations might be taking risks here. We note that there are laws in Canada that could potentially require organizations to exercise greater due diligence. In particular, organizations may need to improve their takedown policies and procedures to avoid knowingly (or recklessly) continuing to publish and transmit intimate images on their platforms when the person depicted in the image states that they did not consent.

- Privacy: Most platforms prohibit users from violating the privacy rights of others. When organizations did explain what they meant by this, it was clear that privacy did not mean control over personal information except for certain sensitive information. It would appear, therefore, that the right to privacy is more limited to a right that can be legally enforced under statutes and common law. One might query, however, whether part of being transparent and accountable for personal information on a platform requires a commercial organization to describe in greater detail what respect for the privacy rights of others means and to provide a method of redress.

- Takedown Procedures: Many organizations had takedown procedures for code of conduct violations. However, the ease of use of those procedures varied significantly. We found this curious. There would seem to be at least a plausible argument that a platform is engaged in the commercial activity when it acts as a professional agent for the user to process and distribute personal information. This would seem to have a number of implications both under PIPEDA and other laws and may be a fruitful avenue for the OPC to consider.

Although our sample size was small, our findings were remarkably similar across sites. There are clear industry practices. Where there is an outlier, it is striking and it is usually possible to trace the issue back to a demonstrable ideological choice by the site — such as to place freedom of expression above other values. Nevertheless, we are of the view that further research could and should be conducted.

What is also striking, albeit predictable, is that the stated practices of sites appeared to be directly related to a risk calculus. Sites that could be expected to have a higher number of uncivil interactions or could be used to cause harm were much more likely to have robust policies and tools. Sites that were more tightly controlled with more limited ability for interaction had fewer policies and tools. Similarly (and again, predictably), where the law was crystal clear, the issue was addressed by the site. The most striking example was copyright. Sites had clear copyright policies and mechanisms to submit a takedown request. Most sites expressly cited and followed the prescriptive DCMA. Where the law was murky, the site was more likely to be softer on the issue. Misuse of another’s personal information was an example. Where there was a divergence between risk and the site’s practices, it appeared to be related to an ideological choice and not happenstance.

In the end, we found that most sites offered numerous ways in which the operators of social platforms or social functions within sites could control and regulate the behaviour of the users of those platforms and functions. What is not clear is whether these tools are being implemented. We wonder whether, under the principles of openness, fairness, transparency and accountability, organizations should be informing users more clearly whether they actually act on complaints, how they resolve complaints, how often they remove content and how often they block users who violate the rules. Is such information important to appreciating the consequences of posting personal information on a site and, therefore, important to obtaining informed consent from users? We also wonder whether an organization that makes an ideological choice to prioritize a value such as freedom of speech over other values should be accountable for the consequences of that choice. If an organization is essentially making money from the sale of advertising on a site that is hosting—recklessly or with willful blindness—copies of sexually explicit photos without any easy-to-use takedown mechanism, should that organization be vicariously liable for whatever harm ensues? Can or should this liability be traced back further? Should the host of a site that has no policies and takedown mechanisms be liable? How far up the chain would one go? These issues go beyond the scope of this submission but may be fruitful to consider.

Investigation Sample

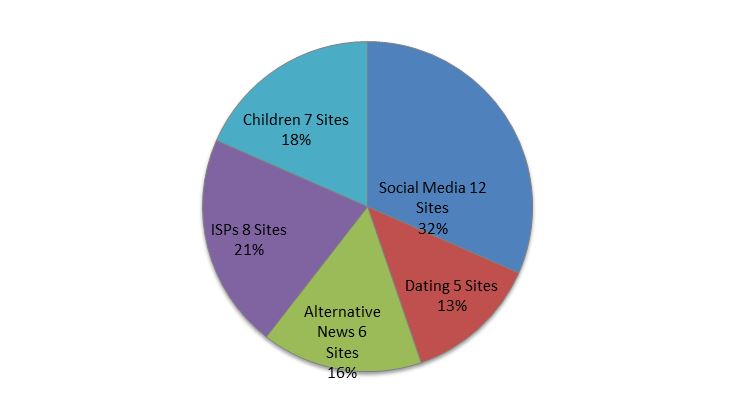

As noted, our investigation was limited to an initial sample of 38 websites, including social media sites, dating sites, alternative news media or crowd-sourced news, and internet service provider sites.Footnote 10 In the case of internet service providers, we primarily reviewed Canadian internet service providers and included major telecommunication providers and challengers. Illustration 1 shows a breakdown of our sample.

Illustration 1 — Sample Composition

Text Version: Illustration 1 — Sample Composition

Illustration 1 — Sample Composition

| Type of Web Sites | Number of Sites in Sample | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Social Media | 12 | 32% |

| Dating | 5 | 13% |

| Alternative News | 6 | 16% |

| ISPs | 8 | 21% |

| Children | 7 | 18% |

| Total Sample | 38 | 100% |

The majority of the sites we chose were well-established sites in their category or emerging in popularity. The sample was, therefore, biased towards sites that would be expected to have rigorous governance programs responding to perceived legal rights or predominant social values. To the extent that these sites already had robust takedown policies, a mandatory obligation to provide takedown rights would not involve a new business practice for those organizations.

What We Examined

We examined the “Terms of Use”, “Privacy Notice” and any “Code of Conduct” or similar documents for each site for certain indicators that suggested that the site held users to standards of conduct and provided users or non-users with a method to report violations to have material taken down by the organization. In particular, we examined the websites for the following restrictions:

- Copyright restrictions: We reviewed the terms of use of each website to determine whether there were restrictions on copyright infringement.

- Age: We examined whether the website restricted use to individuals who had reached the age of majority or to children over the age of 13.

- Anonymity: We reviewed the terms of use and sign-up process to determine whether users could post content anonymously.

- Code of conduct: We examined the terms of use of each website to determine whether there were restrictions relating to: (i) bullying or harassment; (ii) pornography; (iii) nudity or explicit images; and (iv) violation of another person's privacy.

- Reporting mechanisms: We considered whether each website offered clear instructions or a method to report violations of the code of conduct or violations of intellectual property rights.

- Right to erasure: We examined the terms of use to assess whether the organization was offering a right to erasure and, if so, whether there were any restrictions on who could access that right.

What We Found

Copyright

All sites prohibited users from violating the copyright and other intellectual property rights of others. All sites but one (a Canadian-based site) offered a clear method to report copyright violations in order to initiate a takedown. The influence of the DCMA loomed large with majority of organizations expressly following the DCMA provisions. It appears safe to conclude that sites located in the U.S. or that have a significant U.S. presence were influenced by the safe harbor from liability for service providers who implement the DCMA’s prescriptive notice-and-takedown procedures and otherwise comply with the conditions set out in section 512 of the DCMA.

Copyright can be a tool for online reputation management.Footnote 11 An analysis of who owns the copyright in a digital image in Canada and the U.S. and the Copyright Modernization Act in Canada goes beyond the scope of this submission. However, at least since 2012, the general rule has been that the person who takes the photograph will be the owner of the image. Copyright can, therefore, be a key legal tool for individuals to control their reputation when all of those selfies are repurposed without their permission.

However, none of the sites we examined had easy-to-find information on whether and how often they had received takedown requests. Certainly none offered statistics on whether the requests were tied to reputation. The OPC might consider investigating this issue to understand whether and to what extent copyright laws provide a meaningful and practical way to address the issue.

Obtaining empirical evidence is important because there are numerous exceptions. The limits of copyright are evident in the case of Terry Bollea (also known as the wrestler “Hulk Hogan”) and Gawker Media over the publication of an excerpt from a video of Mr. Bollea having sex with a friend’s wife. In an effort to shut down the continued publication, Mr. Bollea purchased the copyright to the video from the videographer and then sought to enjoin its publication. The court rejected the injunction concluding that the claim was bound to fail under the U.S. fair use doctrine.Footnote 12 Canada has similar “fair dealing” exceptions. Moreover, in Canada, where there is no "takedown" regime, the assertion of copyright as the basis for having material removed would depend upon the cooperation of the service provider than any compulsion based on preserving a safe harbour.

Copyright has significant limitations. The Catsouras family could not rely on this tool to remove the photos of their deceased daughter, Nikki, who died in a car accident in 2006. The gruesome accident scene images of Nikki taken by the California Highway Patrol were subsequently shared by two employees.Footnote 13 Searching Nikki’s name in Google resulted in the images, which had gone viral. The California Highway Patrol refused to surrender copyright of the photographs, leaving the Catsouras family with suing the enforcement agency for various grounds including invasion of privacy, and with the assistance of an online reputation service, successfully requesting at least two thousand websites to remove the images.Footnote 14

Age Limitations and Right to Erasure

In Canada, the OPC discourages the collection of personal information from children 13 years of age and under.Footnote 15 In the United States, the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (“COPPA”) requires verifiable parental consent before collecting personally identifiable information, as defined in COPPA, of children 13 years of age and under.Footnote 16 On January 1, 2015, the “California Online Eraser Law” came into force in the U.S. providing a minor with the right to remove content or information that they posted to a website, application or online service as a registered user.

We were interested in assessing whether minors, and especially children, were being discouraged from using sites through age restrictions and whether those sites that seemed to permit minors to participate offered clear guidance on the minor’s right to erasure in the Terms of Use.

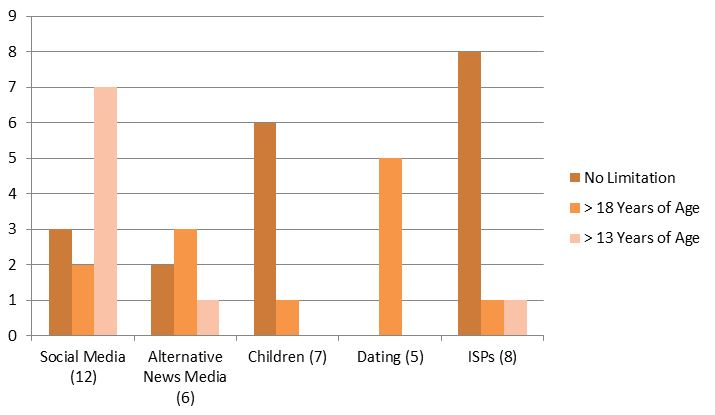

Interestingly, one messaging App included in the social media category prohibited minors. Another prohibited children under 13. However, most sites set the restriction at 13 years of age. However, there were three sites that did not include an age restriction.

For the most part, the children’s sites did not contain an age restriction. One site had an express age restriction to certain parts of the site that were directed to adults. We did not test whether the children’s sites had COPPA-compliant mechanisms for obtaining verifiable parental consent. However, from a cursory review, we do believe that this was always the case.Footnote 17

Illustration 2 — Age Limitations

Text Version: Illustration 2 — Age Limitations

Illustration 2 — Age Limitations

| Type of Web Sites | No Limitation | > 18 Years of Age | > 13 Years of Age |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Media (12) | 3 | 2 | 7 |

| Alternative News Media (6) | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Children (7) | 6 | 1 | 0 |

| Dating (5) | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| ISPs (8) | 8 | 1 | 1 |

There is social value in teenagers having access to news media. News media sites and internet service provider sites may not be particularly appealing sites for young children. Therefore, the use of the interactive functions of these sites (comment features, contributing content) may not be particularly concerning. However, one of these sites was truly a crowd-sourced site and, as will be discussed below, had few limitations on the type of content that could be posted.

We found that only one website that we reviewed offered minors an explicit right to have content that they posted removed. Interestingly, this site was an alternative news media site and not a social media or children’s site. By contrast, many sites, including children’s sites expressly required users to provide the site with an irrevocable license to use and post content that was uploaded to the site.

Individuals under the age of majority in Canada lack the legal capacity to enter into a binding agreement with the website operator.Footnote 18 These contracts may only be enforced against the minor if they fall into the category of contracts of service and that are not harmful to the minor.Footnote 19 This is, however, a very limited category of contract. It is far from clear that terms of use or permission to use a photograph of the minor out of context or in a manner that could harm the minor would fall within the realm of enforceable contracts. It is questionable whether the minor could be required to accept the risks of posting content that is later misused.

It is questionable, therefore, whether sites that do not restrict their use to adults could preclude a user from exercising a right to erasure of content that the minor posted. If the website operator does not have an enforceable license to display and publish the material that has been uploaded by a minor, on what basis could the website operator refuse to take that material down if requested by the minor or when the minor becomes an adult (provided that the adult has not assented to the terms of use by continued use of the website)? Another interesting question is whether the organization could refuse to honour a takedown request by a minor who appears in a photograph of another user who is a minor. The minor who is the object of the photo lacked the legal capacity to consent to the use of his or her image in this way.

We conclude that the issue of the legal rights of minors is an area that requires further consideration and review. Is this a basis that could be used by young individuals to obtain a type of right to erasure?

Anonymity

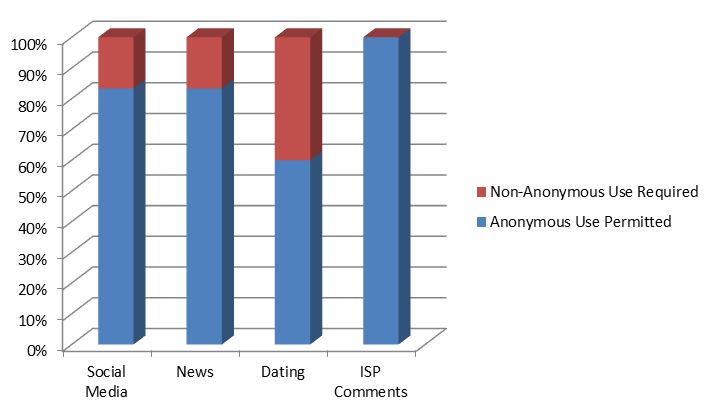

We found that most sites did not have restrictions requiring a user to use his or her real name in order to post content or comment on posts of others.

Illustration 3 — Anonymous Use

Text Version: Illustration 3 — Anonymous Use

Illustration 3 — Anonymous Use

| Type of Web Sites | Anonymous Use Permitted | Non-Anonymous Use Required |

|---|---|---|

| Social Media | 10 | 2 |

| News | 5 | 1 |

| Dating | 3 | 2 |

| ISP Comments | 8 | 0 |

Many online sites, especially online news sites, include features that permit readers to contribute their views and opinions to published articles. This creates a space for readers to grapple with topics that matter to them. Such online participation has democratized publishing and provided an opportunity for diverse voices to emerge. Many comment features allow for the use of pseudonyms in such contributions. This can provide a cover for abusive commentary. As noted by Christopher Wolf, the chair of the Anti-Cyberhate Committee of the Anti-Defamation League, many comment sections have failed because of lack of accountability.Footnote 20 It is postulated that those who can hide behind anonymity feel more free expressing repugnant views. Consequently, there is a possibility that identifying commentators would make these commentators think twice about associating their names with comments that society would deem offensive, abusive or otherwise unpopular, fearing consequences by employers, family and friends.Footnote 21 And yet, there is an important social function in allowing individuals to engage in political and social speech without fear of retaliation. The Supreme Court of Canada has stated that a degree of anonymity may be essential to personal growth and the flourishing of a democratic society and, therefore, may be the foundation of a privacy interest that is protected against unreasonable search and seizure.Footnote 22 Furthermore, anonymity can be a shield against harassment. One can imagine the consequences if every person responsibly and respectfully posting an unpopular position challenging a social norm were required to use his or her real name.

Moderating whether comments offend the websites community standards is costly and time-consuming for organizations. On the other hand, online anonymity complicates the ability of individuals who are the subject of online defamation or harassment to take legal steps against those who post this type of content. An individual may need to obtain a court order to require the platform to disclose information that could identify the user. The individual may not obtain sufficient information from the platform and have to go to the internet service provider for additional assistance.

Recently, online media sources have either removed their comment features or redesigned the features requiring individuals to comment via their Facebook profile or other online network.Footnote 23 Canada’s own national broadcaster, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, announced in March 2016 that it will amend its commenting policy to require online commenters to use their real name, in the ”interests of encouraging civil conversation.”Footnote 24 The policy change was fast-tracked in the wake of a complaint by a group of Francophones over what they perceived as hateful comments regarding New Brunswick’s French-speaking community.Footnote 25 Using Facebook or other means to publicize identities mitigates the abuse of the system and reduces the need of the gatekeeping by the organization.

Although online anonymity undeniably complicates the ability of individuals who are harmed to seek legal recourse, it need not be a hurdle to the central issue of ensuring that material that infringes the rights of those individuals to be taken down. The platform is ultimately in control of what is displayed on and through the platform. Therefore, anonymity, pared with a robust takedown procedure may balance rights, ensuring a broad platform for free speech but with some outer limits.

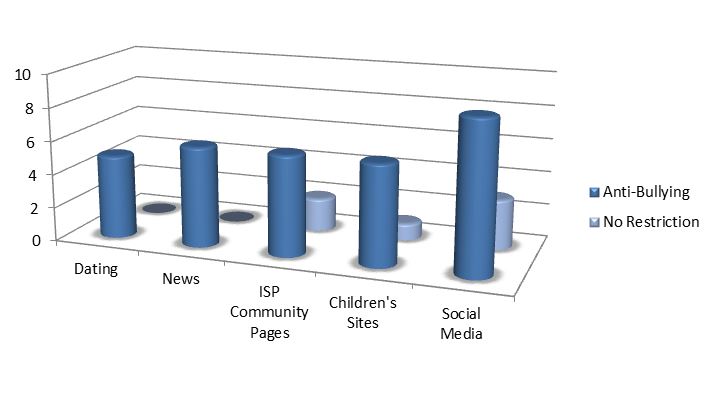

Bullying / Harassment

Anti-bullying and anti-harassment provisions were the norm for most platforms. However, there were exceptions. A child-directed site did not have a provision relating to bullying or harassment. However, this likely reflected the fact that user interaction was very limited and, therefore, there would have been no practical use for the provision. Intriguingly, every news site we reviewed, including those that are crowd-sourced, had an anti-bullying or anti-harassment provision. These were the sites where we would have expected to see greater latitude on the basis that they would have a stronger bias towards freedom of expression. Instead, these sites seemed comfortable drawing a line at speech that was bullying or harassing. By contrast, some social media sites were silent on bullying or harassing behaviour or limited the restriction to hate speech. The community pages of internet service providers (particularly Canadian ISPs) did not expressly restrict bullying or harassing behaviour. However, these communities were not highly active (most comments were service complaints directed to the ISP) or may have been subject to greater moderation.

Illustration 4 — Anti-Bullying and Harassment

Text Version: Illustration 4 — Anti-Bullying and Harassment

Illustration 4 — Anti-Bullying and Harassment

| Type of Web Sites | Anti-Bullying | No Restriction |

|---|---|---|

| Dating | 5 | 0 |

| News | 6 | 0 |

| ISP Community Pages | 6 | 2 |

| Children’s Sites | 6 | 1 |

| Social Media | 9 | 3 |

The test for criminal harassment is very high in Canada.Footnote 26 In order to secure a conviction for criminal harassment pursuant to s. 264 of the Criminal Code, RSC 1985 c 46, the prosecution must establish beyond a reasonable doubt that the victim of the harassment reasonably feared for his or her safety or the safety of another person known to the victim and that the accused knew that the victim was harassed by the communication or was reckless as to whether the victim was harassed.

Nova Scotia enacted anti-bullying legislation in 2013.Footnote 27 The legislation provided for a number of protective orders in relation to electronic communications that were intended or ought reasonably to be expected to cause fear, intimidation, humiliation, distress or other damage or harm to another person’s health, emotional well-being, self-esteem or reputation, and includes assisting or encouraging such communication in any way. In Crouch v. Snell,Footnote 28 the legislation was held to be unconstitutional for, among other things, unreasonably interfering with freedom of expression. A discussion of the court’s decision goes beyond the scope of this submission. However, this episode illustrates the difficulty in regulating this area.

The tort of intentional infliction of mental suffering is recognized in Canada. The plaintiff is required to prove on a balance of probabilities that the defendant engaged in flagrant or outrageous conduct calculated to produce harm to the plaintiff and that the plaintiff suffered a provable illness. The harm must be intended or known to be substantially certain to follow the act.Footnote 29

To date, appellate courts have not yet clearly recognized a civil tort of harassment.Footnote 30 The courts have postulated that the elements of this tort are: (i) outrageous conduct by the defendant; (ii) the defendant’s intention of causing or reckless disregard of causing emotional distress; (iii) the plaintiff’s suffering of severe or extreme emotional distress; and (iv) actual and proximate causation of the emotional distress by the defendant’s outrageous conduct.Footnote 31

The intentionality required in the tort of intentional infliction of mental suffering and the putative tort of harassment are significant limiting conditions on liability. They may also serve to insulate the platform from liability for the activities of its users. However, this is not certain. In Evans v. Bank of Nova Scotia,Footnote 32 the Ontario Superior Court certified a class action against the bank on the basis of vicarious liability for intrusion upon seclusion on the basis of allegations regarding lack of controls and supervision. Could a platform be liable for ongoing activities of a user that are calculated to cause emotional distress, once those activities are brought to the platform’s attention? This is an issue that is far from settled.

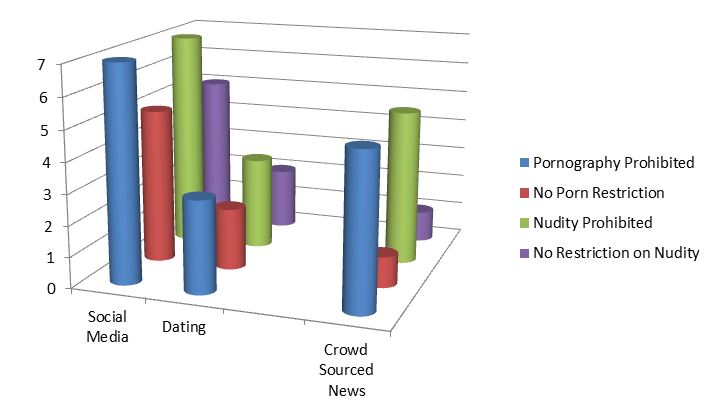

Pornography and Nudity

Perhaps not surprisingly, there is little consensus on pornography and nudity in the terms and conditions for social sharing. Most crowd-sourced news media sites limit or prohibit pornography and nudity in posts. However, there is much less consistency in social media and dating sites. The dating sites may be of less concern given the nature of those sites, although they do give rise to the potential for scraping of images or using images that are shared there onto other social media sites.

Some of the social media sites we reviewed stated that users who posted sexually explicit or nude photos must use a “NSFW” (not suitable for work) tag. These platforms seemed to have substantial numbers of users who explicitly claimed that they believed the photos they were publishing were in the public domain (simply by “finding them on the Internet”) and that an individual appearing in a posted photo could contact the user to have the image removed.

None of the websites that permitted nudity or pornography expressly imposed on the user an obligation to have the consent of the individual depicted in the image or even a reasonable belief that the person in the image consented to its circulation, although arguably this might be understood as implicit in prohibitions on the violation of an individual’s privacy, where this prohibition was included in the terms of use.

Illustration 5 — Intimate Images

Text Version — Illustration 5 — Intimate Images

Illustration 5 — Intimate Images

| Type of Website | Pornography Prohibited | No Porn Restriction | Nudity Prohibited | No Restriction on Nudity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Media | 7 | 5 | 7 | 5 |

| Dating | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Crowd Sourced News | 5 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

In Canada, it is an offence under s.162.1 (1) of the Criminal Code to knowingly publish, distribute, transmit, sell, make available or advertise an intimate image of a person knowing that the person depicted in the image did not give their consent to that conduct, or being reckless as to whether or not that person gave their consent to that conduct. An intimate image is any visual recording in which the person is nude, is exposing his or her genital organs or anal region or her breasts or is engaged in explicit sexual activity and at the time of the recording there were circumstances that gave rise to a reasonable expectation of privacy and there remains a reasonable expectation of privacy at the time the offence is committed.

The boundaries regarding what might be considered to be “reckless” and the application of this law to foreign-based platforms publishing images in Canada would appear to be ripe areas for consideration. When the intimate images offence was introduced in Parliament, the Canadian Bar Association made submissions raising these very concerns that an online service provider could be exposed to criminal liability and suggested an amendment to protect those providers.Footnote 33 This amendment was not adopted by Parliament. Interestingly, however, online platforms have not yet taken any visible steps to increase their diligence to avoid a charge of “recklessness”.

Manitoba has enacted legislation to protect against the online publication of intimate images without consent.Footnote 34 Unlike the federal legislation, the Manitoba law requires that the individual know that the image is being distributed without consent. It would seem probable that once the lack of consent is brought to the attention of the platform, the continued distribution of the image by that platform would fall within the provisions of the statute. Accordingly, one might expect to see a movement to robust take-down procedures for platforms that permit the publication of this type of conduct, assuming the law could withstand a challenge for being unconstitutional.

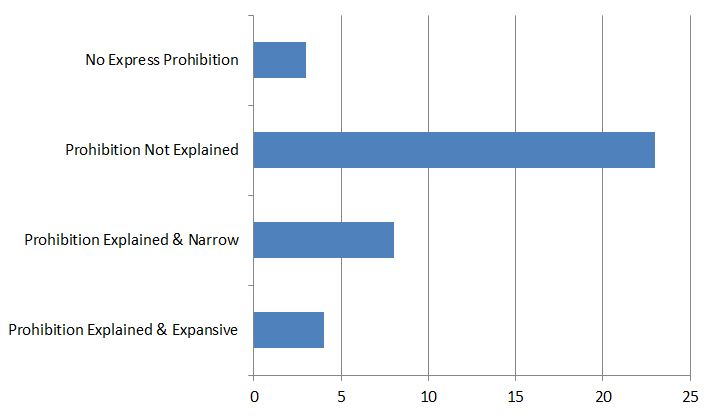

Violation of Privacy

Many sites that we reviewed for the purposes of this submission had express prohibitions on users violating the privacy of others. The only exceptions were certain internet service provider comment forums. The problem, however, is that an individual’s privacy right was rarely explained. If it was explained, it may be limited to compliance with privacy laws or to certain categories of information such as credit card numbers and non-public contact information. However, in a few cases, the platform provided a more expansive definition of what might constitute a privacy violation. One platform went as far as to say that any use of personal information of another user of the site without express consent was prohibited.

Illustration 6 — Prohibitions on Privacy Violations

Text Version — Illustration 6: Prohibitions on Privacy Violations

Illustration 6: Prohibitions on Privacy Violations

| Type of Prohibition | Number of Sites |

|---|---|

| No Express Prohibition | 3 |

| Prohibition Not Explained | 23 |

| Prohibition Explained & Narrow | 8 |

| Prohibition Explained & Expansive | 4 |

At a minimum, in Canada, the violation of a privacy right would appear to encompass privacy rights under Quebec’s Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms,Footnote 35 the provincial statutory privacy torts,Footnote 36 and the emerging common law torts.Footnote 37

In certain provinces, statutory frameworks expressly set out a right of protection rooted in tort law. For example, the B.C. Privacy Act, makes actionable the wilful violation of the privacy of another, without requiring any proof of damage, and establishes a number of defences/exceptions.Footnote 38

Privacy rights are also increasingly recognized in the ever-evolving common law. The 2012 Ontario Court of Appeal ruling in Jones v. Tsige, 2012 ONCA 32 recognized the common law tort of inclusion upon seclusion in the context of a bank attendant repeatedly viewing the bank records of an individual who was the ex-wife of the bank attendant’s domestic partner. The court ruled that to make out the cause of action,(1) the conduct must be intentional (2) , the defendant must have invaded, without lawful justification, the plaintiff’s private affairs or concerns; and (3) a reasonable person would regard the invasion as highly offensive, causing distress, humiliation or anguish.Footnote 39 Considered by the court to be an incremental step to develop the common law with the changing needs of society,Footnote 40 it is nevertheless significant to observe the court embrace the importance for the common law to respond to problems posed by technological advances and the creeping ability to collect and aggregate personal information in electronic forms that are readily accessible.Footnote 41

The common law right to privacy has also been considered and expanded in the Ontario Superior Court decision released earlier this year, Jane Doe 464533 v. D. (Jane Doe), which recognizes a tort of public disclosure of private facts in Ontario. Observing that there should be legal recourse against a defendant who distributed privately-shared and intimate video recording of the plaintiff on the internet, Judge Stinson found a cause of action for invasion of another’s privacy in circumstances where person publicizes a matter where it (1) would be highly offensive to a reasonable person, and (2) is not of legitimate concern to the public.Footnote 42

Does (or should) a prohibition on violating the privacy rights of others be limited to these laws? Having encouraged such sharing as its business model, does the platform have any responsibilities under the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act to outline what it will do with that information on its platform? The platform is, after all, merely a platform — a service provider to the individual who wishes to share information. On the other hand, the platform’s business model could be said to use personal information, given that its raison d’être is the sharing of personal information. It would be seem unworkable and unnecessary for organizations to be gatekeepers and moderators of all content on its platform. However, one might ask whether the platform is free altogether from any obligation to explain in greater detail what privacy rights are protected and to respond to complaints about violations of those rights. At some point, might the platform be vicariously liable if it does nothing?

What is clear is that at present the protection of privacy rights by platforms is frequently vague. Without published statistics or examples of the types of requests that will be honoured, it is far from clear that current prohibitions on privacy violations contained in terms of use have any meaningful effect on protecting individuals with any protections. One avenue for further exploration and research would be to obtain information from platforms regarding how they handle complaints and the types of conduct that either is or is not accepted as being privacy violations.

Reporting Code of Conduct Violations

It is clear from our analysis that if the law offers a clear safe harbour to organizations, organizations will take it. The DCMA is an example of how a safe harbour will lead organizations to implement clear and simple to use methods for reporting copyright violations.

Although the majority of sites offered a method of reporting other violations, the reporting methods were often not clear or were cumbersome (involving multiple steps). In some cases, the reporting methods were simpler on websites but virtually impossible within the App. For example, one App required URLs for content that violate the terms of use. URLs were not available within the App.

We found the lack of transparency and ease of use of reporting violations to be curious. The “flag” system is well-recognized and can be used to partially automate requests by allowing users to identify what the issue is with the content. Nevertheless, some sites had not yet incorporated this type of solution. Most that did implement a reporting solution did not provide examples of situations in which they would act. This left the user with no guidance on what the user could expect from the organization.

This leads us to a final observation. Is there any risk for an organization under PIPEDA of being criticized for not collecting registration and usage information by fair and lawful means if the organization is inviting the individual to rely on chimerical codes of conduct? In other words, if a user relies (or is deemed under consumer protection legislation to rely) on codes of conduct as a reason for why it may be safe to participate, does this have an impact on informed consent of the user to information collected by the organization? Even if the platform is not collecting or using personal information in its own right, does it affect informed consent to the processing the information and distributing it over the Internet on behalf of the user of the platform? Taking this one step further, although the user may be acting for non-commercial purposes, the platform, as a professional service provider, may be engaged in commercial activities while processing and distributing information on behalf of the user. Can such a platform distance itself from improper use of personal information by a user if the platform provides no mechanism to address that improper use?

We hope that this submission proves useful to the OPC in its consideration of these thorny problems. Clearly, organizations’ takedown policies have some utility in balancing reputational rights and other values such as freedom of expression. In our view, these policies are necessary to manage organizational risk and not merely “voluntary”. However, it is also clear that they are not sufficient, at present, but may evolve in response to legal obligations of platforms maturing.

Yours truly,

Timothy M. Banks, Liane Fong, and Karl Schober

- Date modified: